Winter 2018 Edition

Winter 2018 Sagesse Publication

- Introduction to Sagesse

- A Record of Service, Bob Morin, CRM. By Sue Rock

- Un recit de service – Bob Morin, CRM. By Sue Rock

- CAN/CBSG 72.34-2017 (French). By Sharon Byrch, Uta Fox & Stuart Rennie

- CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017 (English). By Sharon Byrch, Uta Fox & Stuart Rennie

- Metadata in Recent Canadian Case Law. By Joy Rowe

- Privacy-Driven RIM in Ontario’s Universities. By Carolyn Heald

Biographies

Sharon Byrch is an experienced local government records and privacy manager, working for the Capital Regional District in Victoria, BC. Her mission is helping government digitize and overcome information chaos by optimizing valuable information assets as a ‘single source of managed truth’ through applied IM/ERM strategy, learning and effective partnerships.

Uta Fox, CRM, FAI is the Manager of Records and Evidence Section, Calgary Police Service. She holds a Master’s Degree from the University of Calgary, is a Certified Records Manager and in 2017, made a Fellow of ARMA International – #55. Uta represented ARMA Canada on the Canadian General Standards Board Committee that updated CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017 Electronic records and documentary evidence.

Carolyn Heald is Director, University Records Management and Chief Privacy Officer at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. She started her career as an archivist at the Archives of Ontario before moving into policy and records management. Later, she took on both privacy and records management at York University in Toronto. She holds an MA in History and a Master’s of Library Science, and is a Certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP/C) from the International Association of Privacy Professionals.

Stuart Rennie, JD, MLIS, BA (Hons.) has a Vancouver, Canada-based boutique law practice where he specializes in records management, privacy and freedom of information, law reform, public policy and information governance law. He is a member of ARMA International’s Content Editorial Board. Stuart is also an adjunct professor at the School of Library, Archival and Information Studies at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Sue Rock, CRM, is owner of The Rockfiles Inc. and an operating partner of Trepanier Rock®, with a focus on ensuring records management principles are embedded into all information management solutions. She is an active supporter of ARMA. Sue influences friends and colleagues with her enthusiasm for historical content captured in ARMA’s IM journals.

Joy Rowe is the Director of Records Management Compliance for a private sector company in metro Vancouver, and she previously worked as the Records Management Archivist at Simon Fraser University. She is a graduate of the School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies at University of British Columbia. She has published articles and presented on topics such as openly-licensed training tools for records creators, accessibility and universal design, and human rights and records. She was one of six selected from an international pool to be part of the 2017-2018 New Professionals Programme of the International Council on Archives.

Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management an ARMA Canada Publication Winter, 2018 Volume III, Issue I

Introduction

ARMA Canada is pleased to announce the launch of its third issue of Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management, an ARMA Canada publication.

This latest edition features a biography of an ARMA Canada pioneer, a thorough review of metadata, a discussion of the Canadian General Standards Board updated CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017 Electronic records as documentary evidence and a look at privacy challenges at Ontario’s universities in regards to records management.

One of the goals of Sagesse’s editorial team is to honour and bring forward former Canadian members involved with ARMA Canada / ARMA International who have made significant contributions to ARMA and the records and information management (RIM) and information governance (IG) industries. Sue Rock, CRM, accepted this challenge and provided a biography of Bob Morin, CRM. Bob was a founding member of ARMA Canada Region, a founding member of three of ARMA Canada’s chapters and a champion of ARMA International. To learn more about his tremendous achievements, see “A Record of

Service: Bob Morin, CRM,” in this issue. This article has been translated into French.

“Metadata in Canadian case law,” by Joy Rowe is a thorough exploration of metadata and its value focusing on admissibility as well as records identification, retrieval and assisting in the authenticity and integrity of records systems. As well, the article examines case law including those related to the business records exception to the hearsay rule, the best evidence rule and evidence weight, use of standards in authentication and computer-generated versus human-generated electronic records.

And in keeping with the admissibility of electronic records, Sharon Byrch, Uta Fox, CRM, FAI and Stuart

Rennie collaborated to write “The New CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017 Electronic records as documentary

evidence.” They discuss the major changes made from the 2005 version to that of 2017 in regards to legal issues, records management and information technology. The authors wish to thank the Canadian General Standards Board for reviewing this article. Please note: this standard is now available in both French and English and can be obtained at no cost on their website (see the article for the links). This article has also been translated into French.

Carolyn Herald examines “Privacy-Driven RIM in Ontario’s Universities” and the role of privacy as a means of implementing records management in Ontario’s universities. Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) was amended in 2014 and since then more and more universities have established records management programs because of the recordkeeping amendments. This article is relevant to RIM/IG practitioners in all other industries.

We would like to take this opportunity of thanking you, the RIM and IG professionals that access and use the information in these issues in your workplaces and for education and / or training purposes.

Sagesse’s articles have been downloaded from hundreds of times to over 18,000 downloads. That means this information is relevant, useful, practical and appreciated; ARMA Canada is most pleased to be able to provide this content for you.

Please note the disclaimer at the end of this Introduction which notes that the opinions expressed by the authors are not the opinions of ARMA Canada or the editorial committee. Whether you agree or not with this content, or have other thoughts about it, we urge you to share them with us. If you have recommendations about the publication we would appreciate receiving them. Forward opinions and comments to: armacanadacancondirector@gmail.com.

If you are interested in providing an article for Sagesse, or wish to obtain more information on writing for Sagesse, visit the ARMA Canada’s website – www.armacanada.org – see Sagesse.

Enjoy!

ARMA Canada’s Sagesse’s Editorial Review Committee:

Christine Ardern, CRM, FAI; John Bolton; Alexandra (Sandie) Bradley, CRM, FAI; Stuart Rennie and Uta Fox, CRM, FAI, Director of Canadian Content.

Disclaimer

The contents of material published on the ARMA Canada website are for general information purposes only and are not intended to provide legal advice or opinion of any kind. The contents of this publication should not be relied upon. The contents of this publication should not be seen as a substitute for obtaining competent legal counsel or advice or other professional advice. If legal advice or counsel or other professional advice is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.

While ARMA Canada has made reasonable efforts to ensure that the contents of this publication are accurate, ARMA Canada does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, currency or completeness of the contents of this publication. Opinions of authors of material published on the ARMA Canada website are not an endorsement by ARMA Canada or ARMA International and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of ARMA Canada or ARMA International.

ARMA Canada expressly disclaims all representations, warranties, conditions and endorsements. In no event shall ARMA Canada, it directors, agents, consultants or employees be liable for any loss, damages or costs whatsoever, including (without limiting the generality of the foregoing) any direct, indirect, punitive, special, exemplary or consequential damages arising from, or in connection to, any use of any of the contents of this publication.

Material published on the ARMA Canada website may contain links to other websites. These links to other websites are not under the control of ARMA Canada and are merely provided solely for the convenience of users. ARMA Canada assumes no responsibility or guarantee for the accuracy or legality of material published on these other websites. ARMA Canada does not endorse these other websites or the material published there.

A Record of Service: Bob Morin, CRM

By Sue Rock, CRM

Introduction

A Record of Service: Bob Morin, CRM coincides with the 150th anniversary of Canada as a country. Bob is one of many Canadian records management pioneers who persevered in establishing records management as a profession.

This tribute focuses on Bob’s achievements within the context of professional organizations such as ARMA and ICRM because Bob believed in the need for common organization.

Bob Morin, CRM died on February 17, 2012 in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Bob was a records management pioneer in the truest sense. Remembered fondly for his personality and humour, Bob carved his career through vision, determination, strength and perseverance. He found inspiration from his ARMA International colleagues both in Canada and the US. He sought to measure his records management competency by receiving his CRM designation. He demonstrated continuous dedication to industry associations such as ARMA and ICRM wherein he formed life-long professional partnerships and a multitude of personal friendships.

ARMA – How contributions are measured and documented for enduring historical perspective

ARMA employs a system of categories comprising leadership, awards, education, publication and presentations to recognize individual efforts to advance the profession of records management. ARMA membership provides opportunities for individual professional growth, and measures success through these hallmarks. Achievements are documented within ARMA’s historic and present journals.

Bob’s contributions to the profession of records management are documented within ARMA International’s archival collection of journals. The journals, currently known as Information

Management, were previously entitled ARMA Records Management Quarterly commencing 1967, and as the title states, they were published four times per year.

Through his membership as documented within professional organizations, such as ARMA and the ICRM, we begin to derive an understanding of Bob’s personal values, his job involvement, his active participation in decision making, and his motivation – the sphere of influence he created.

ARMA – Leadership and the importance of vision

In 1978 the ARMA Canada Region, designated at the time as “Chapter VIII” was inaugurated. This milestone was achieved through a devotion of time and effort by founding Canadian Chapter Presidents including Bob Morin, Former Regional Vice Presidents, International Officers and Charter Members who remained active in ARMA for a number of years. We celebrate our current Canada Region status in ARMA International as an outcome of their vision and leadership.

At the same time, Bob represented Canada as voting member Regional Vice President 1978-80 on the Board of Directors, ARMA International. ARMA documents that as Region VIII nominee National Office 1978-1979 “Mr. Morin’s education ranges from archival management to computer sciences.”

Bob focused on the role of technology for managing records. The collective term at the time for individual technologies such as microcomputers, FAX machines, and micrographic equipment, was office automation.

The challenge of rapidly emerging technology solutions to records management problems during this era is strikingly similar to those faced in the 21st century. Identification of the role of technology within Bob’s career is paramount to the direction he championed.

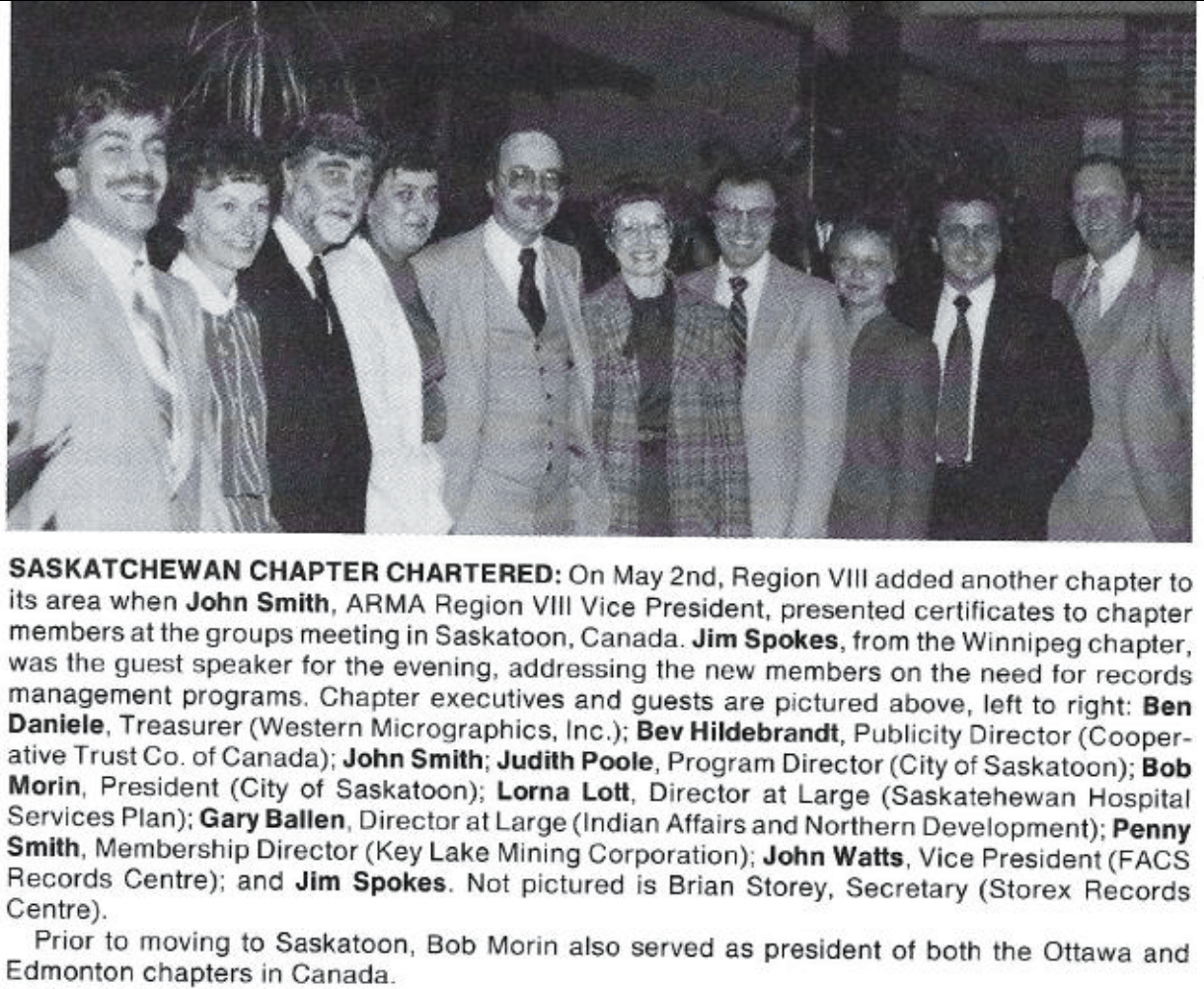

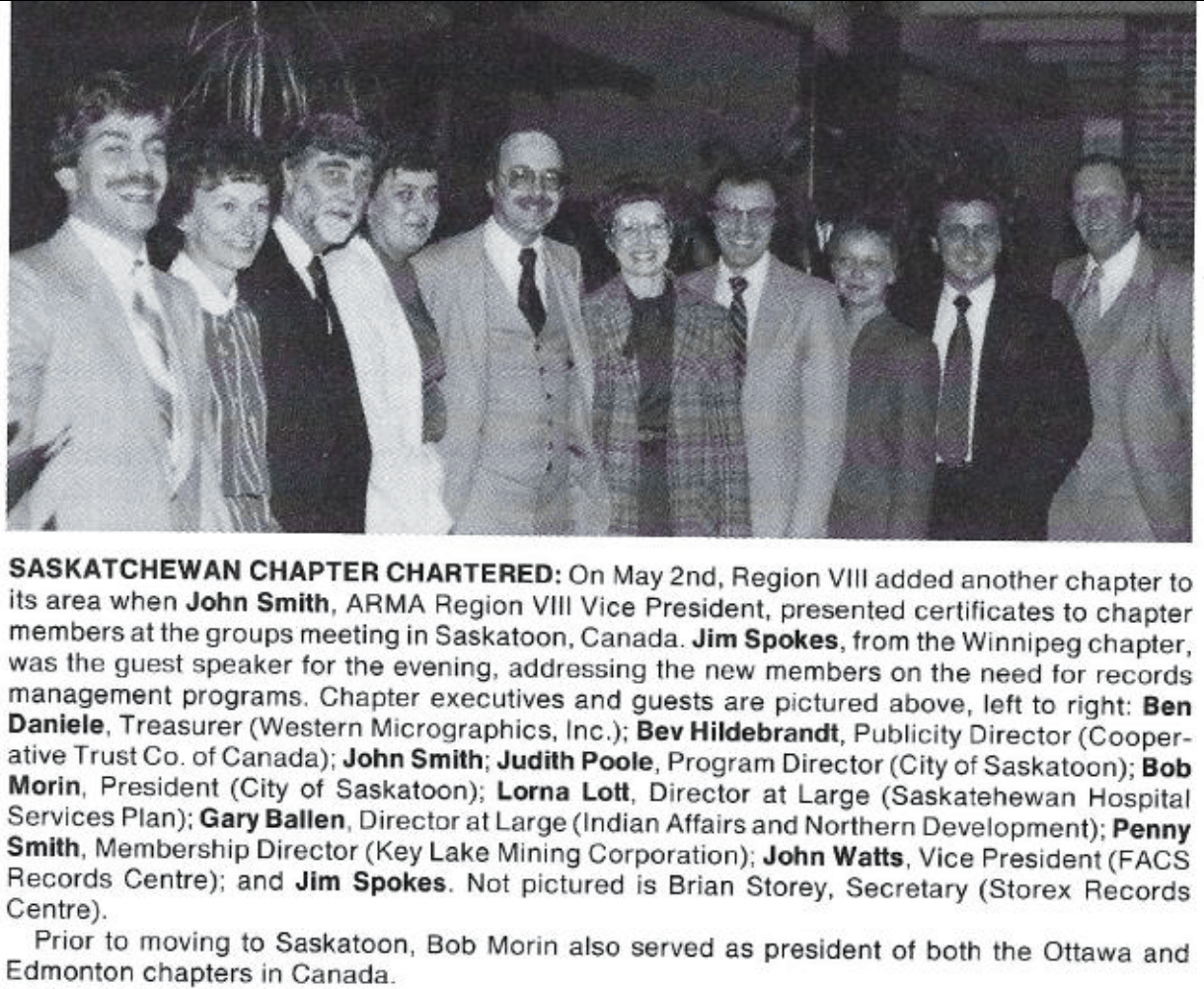

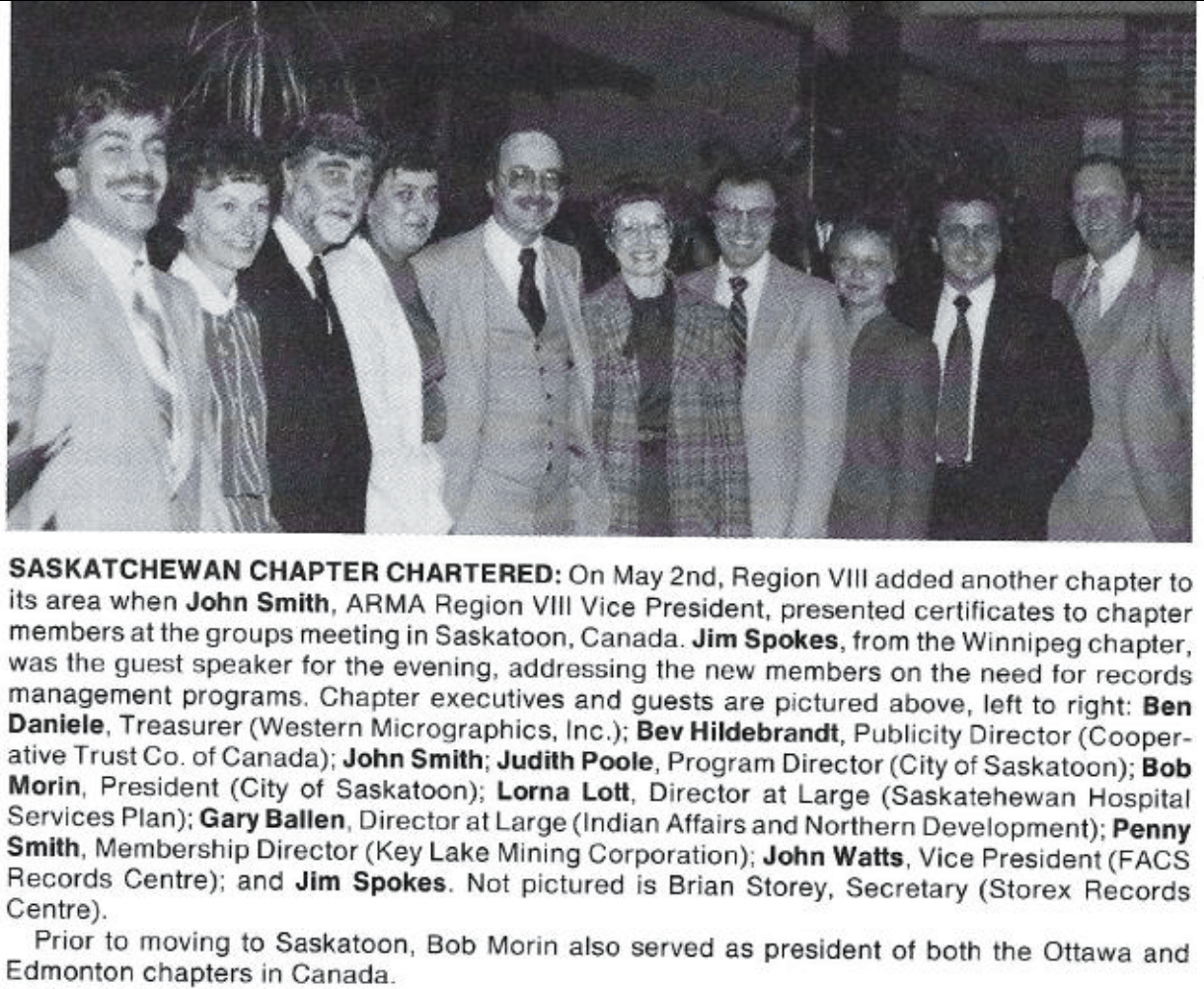

By 1980, Bob had already established two ARMA Chapters within Canada: “He was the founder and first president of the Ottawa chapter…and repeated the same organizational effort recently when he moved to Edmonton.”2 On May 2, 1983 the Saskatchewan Chapter was chartered, with Bob as its President, flanked by a stellar ARMA Chapter team.3

ARMA – Awards and recognition

On the basis of his championing the role of technology within records management, Bob received the first Infomatics Award in 1978 for his efforts in implementing a records management program for the Government of Alberta. This achievement award was sponsored by the ARMA Edmonton Chapter, intended to be presented annually to a “deserving person making outstanding contributions in the information processing field.”4 The award description includes “computing and systems” as one of the three primary areas of information and records management at the time.

The first Canadian Conference on Records Management recruited 252 participants to Banff, Alberta February 4-6, 1980. The conference honoured the “ARMA Canadian Pioneers”. Of course Bob was among them! The group comprised “…founding Chapter Presidents, Former Regional Vice Presidents, International Officers and Charter Members who … remained active in ARMA for a number of years … These pioneers were presented with Certificates of Appreciation at a Pioneer Luncheon at the Banff conference, February 6th, 1980.” The pioneers are named, and they represent seven Canadian Chapters at the time: Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver. 5

An excerpt from one of Bob’s colleagues, Jim Coulson, CRM, FAI breathes life into Bob-the-person with regard to the first Canadian Conference: “Bob Morin, of Saskatoon, was a passionate RIM pioneer who brought records management professionals together from across the country to put on the first Canadian Records and Information conference. Two years later, the conference was held in Montreal, with presentations and proceedings in both official languages. The ARMA Canada conference has since become a highly respected annual event.”6

ARMA – Publication and presentation – hallmarks of contribution

Bob shared his on-the-job experience with the ARMA community through both publication and presentation. These communication channels are highly regarded within the ARMA community.

An article Bob wrote for the The Records Management Quarterly in 1980 entitled “Management Information Systems – a Total Approach” speaks to computer literacy as a continuing theme in his career. The article is not only informs us of the technology components of records management at the time, but also states the importance of integrating the technologies and disciplines: “The approach stresses the need for analysis of clerical systems in the design stages. Cost effectiveness is illustrated by efficient use of all information technologies such as micrographics, word processing, forms design, data processing and library resources.”7

ARMA published an earlier article by Bob in 1976 “Relocating a Records Management Operation”.8 In this article, Bob’s thesis is that the records manager will become involved in office moves due to “his interest in all aspects of paperwork”. These moves vary from a simple re-arrangement to a complete relocation. It provides a step-by-step plan covering both the preparation and the physical movebrequirements of particular value to the records manager. This topic continues to weigh into a records manager’s domain in the 21st century!

In 1983, Bob shared his knowledge in a presentation at the 28th Annual Conference, where the conference theme was “The Emerging Information Economy”. His topic was “What the Records Manager Should Know about Data Processing Systems Documentation”. The synopsis states “…the proper handling of magnetic tapes…How to schedule data processing records such as magnetic tapes, databases, and diskettes will be discussed.”9

ARMA – Promotion of education for records managers

Another cornerstone of ARMA professional activity is the delivery of educational programs. Bob was a leader in this area, too.

While Director of Records Management for the Alberta Government Services from 1975-82, “…he directed an eleven-course Training Program that covered File Management, Records Systems,

Micrographics, Office Automation, Forms Management, and Data Processing…He taught Records Management at the University of Alberta, Faculty of Library Science, where he was instrumental in establishing a Credit Course in Records Management.”10

It has been said by his students and colleagues that Bob was fierce in generosity to help fledglings. He always raised the collective morale of those around him.

As a memorial, the ARMA Saskatchewan Chapter continues to present the Bob Morin Award to a young professional to financially assist with training in the Records Management field.

From ARMA’s checklist for professional status including awards, education, publication, presentation, and sphere of influence, Bob hit the highlights. For any of us who have served in any volunteer capacity one might ponder: “Where did he get the energy?” He didn’t stop with ARMA!

IRMF – International Records Management Federation

In 1978, Bob was named as one of ARMA International’s two delegates to a professional organization called the International Records Management Federation (IRMF).11

Initially, the Federation was designed to serve a world-wide interest that Records Management was experiencing. The The Records Management Quarterly published a column called Outlook for the Federation to share its goals, membership bragging rights, and achievements. “Records Management is no longer an all-American sport although many of we ‘internationals’ still gaze in awe at ARMA – 4800 plus strong and still growing, and what a Management team!”12

By 1982, Bob had graduated to the Federation President’s leadership role.13 A position paper examining the future of the Federation was presented the same year to ARMA International. As a result, a new constitution was reviewed and approved by the Executive Board of the IRMF. It was renamed to International Records Management Council.14 Another “first” for Bob.

ICRM – Institute of Certified Records Managers

Bob went on to assume leadership in and to share his sphere of personal influence with the ICRM — the Institute of Certified Records Managers. He served as an officer of the Board of Regents for the term January 1986 through December 1988.

In conclusion …

Bob is one of many colourful Canadian records management pioneers. Their adaptability, their determination and their drive to achieve have created a remarkable example of excellence in the Canadian records management business scene.

It’s a particular challenge to those of us who remain, or who are new to the profession, to pause, to reflect on their journey. We are in our own records management career hiatus – forging our way, while learning time management skills to prioritize and succeed.

Time for reflection? Consider it a professional vacation. A few minutes to lean backwards into a previous century will reap the reward of inspiration and awe for those who faced very similar circumstances: the influence of society, politics, world events, and, always, the advance of technology.

Bibliography

1”Association News and Events”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Number 3 (1978), 51-52

2”Association News and Events”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Number 3 (1978), 51-52

3”Association News and Events”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 17, Number 3 (1983), 56 4David H. Bell, “Canadian Notes”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 13, Number 2 (1979), 48 5Don H. Bell, “Canadian Notes”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 14, Number 2 (1980), 52 6Jim Coulson, “Some Personal Reflections on the History of RIM in Canada”, 2017

7Robert P. Morin, “Management Information Systems – A Total Approach”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 14, Number 2 (1980) 5-6, 16

8”Records Management Quarterly Cumulative Index of Articles (Annotated) January 1967 – October

1977”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 11, Number 4 (1977), 63

9”28th Annual Conference ARMA The Emerging Information Economy”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 17, Number 3 (1983) 61

10”ICRM Information”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 19, Number 4 (1985), 62

11”Outlook – International Records Management Federation”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Number 2 (1978), 55

12Outlook – International Records Management Federation”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Number 2 (1978), 55

13ARMA Records Management Quarterly April 1982 page 69

14IRMF Reorganizes: Announces New Publications”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 16, Number 2 (1982)

1An emphasis on computer sciences became a key ingredient to Bob’s career in records management.

2ARMA Records Management Quarterly July 1978 pages 51-52

3ARMA Records Management Quarterly July 1983 page 56

4ARMA Records Management Quarterly April 1979 page 48

5ARMA Records Management Quarterly April 1980 page 52

6Some Personal Reflections on the History of RIM in Canada, Jim Coulson, CRM, FAI

7ARMA Records Management Quarterly April 1980 page 5

8ARMA Records Management Quarterly October 1977 page 63

9ARMA Records Management Quarterly July 1983 page 61

10ARMA Records Management Quarterly October 1985 page 62

11ARMA Records Management Quarterly April 1978 page 55

12ARMA Records Management Quarterly April 1978 page 55

Un récit de service: Bob Morin, CRM

par Sue Rock, CRM

Introduction

Un récit de service: Bob Morin, CRM, coïncide avec le 150e anniversaire du Canada en tant que pays. Bob est l’un des nombreux pionniers de la gestion des documents au Canada qui ont persévéré pour l’établissement de la gestion des documents en tant que profession.

Cet hommage se concentre sur les réalisations de Bob dans le contexte d’organisations professionnelles, telles que l’ARMA et l’ICRM, car Bob croyait en la nécessité d’une organisation commune.

Bob Morin, CRM, est décédé le 17 février 2012 à Saskatoon, en Saskatchewan. Bob était un pionnier de la gestion des documents dans le vrai sens du terme. Commémoré affectueusement pour sa personnalité et son humour, Bob a façonné sa carrière avec vision, détermination, force et persévérance. Il trouvait son inspiration parmi ses collègues d’ARMA International, au Canada et aux États-Unis. Il a cherché à mesurer sa compétence en gestion des documents en recevant son titre CRM. Il a fait preuve d’un dévouement constant envers les associations de l’industrie telles que l’ARMA et l’ICRM, où il a formé des partenariats professionnels à vie et une multitude d’amitiés personnelles.

ARMA – Comment les contributions sont mesurées et documentées pour créer une perspective historique durable

ARMA emploie un système de catégories comprenant le leadership, les prix, l’éducation, la publication et les présentations afin de reconnaître les efforts individuels pour faire progresser la profession de gestion des documents. L’adhésion à l’ARMA offre des opportunités de croissance professionnelle aux individus et mesure leur succès grâce à ces caractéristiques. Les réalisations sont documentées dans les revues passées et présentes de l’ARMA.

Les contributions de Bob à la profession de gestion des documents sont documentées dans la collection de revues d’archives d’ARMA International. Les revues, actuellement connues sous le nom de Information Management (Gestion de l’information), étaient auparavant intitulées ARMA Records Management Quarterly (Gestion de documents trimestrielle d’ARMA) à partir de 1967, et comme l’indique le titre, étaient publiées quatre fois par an.

Grâce à son appartenance à des organisations professionnelles telles que l’ARMA et l’ICRM, nous commençons à comprendre les valeurs personnelles de Bob, son implication professionnelle, sa participation active à la prise de décision et sa motivation – la sphère d’influence qu’il a créée.

ARMA – Leadership et importance de la vision

En 1978, la Région canadienne de l’ARMA, désignée à l’époque sous le nom de « Chapitre VIII », a été inaugurée. Ce jalon a été atteint grâce au dévouement en temps et en détermination dont ont fait preuve les présidents de sections canadiennes, tels que Bob Morin, les anciens vice-présidents régionaux, les dirigeants internationaux et les membres fondateurs, qui sont demeurés actifs au sein de l’ARMA pendant plusieurs années. Nous célébrons le statut actuel de notre région dans l’ARMA International grâce à leur vision et leur leadership.

Au même moment, Bob représentait le Canada comme membre votant au poste de vice-président régional 1978-80 au conseil d’administration d’ARMA International. L’ARMA documente que, en qualité de candidat à la Région VIII, Bureau national 1978-1979 « La formation de M. Morin s’étend de la gestion des archives à l’informatique. » 1 L’accent mis sur les sciences informatiques est devenu un élément clé du succès de la carrière de Bob dans la gestion des documents.

Bob s’est concentré sur le rôle de la technologie dans la gestion des documents. Le terme général de l’époque pour les technologies individuelles, telles que les micro-ordinateurs, les télécopieurs et l’équipement micrographique, était la bureautique.

Le défi que représentaient les solutions technologiques émergentes face aux problèmes de gestion des documents de l’époque est étonnamment semblable à celui du XXIe siècle. L’identification du rôle de la technologie dans la carrière de Bob est primordiale dans la direction qu’il défend.

Dès 1980, Bob avait déjà établi deux sections d’ARMA au Canada: « Il a été le fondateur et le premier président de la section d’Ottawa…et a récemment répété les mêmes efforts organisationnels lorsqu’il a déménagé à Edmonton. 2 » Le 2 mai 1983, la section de la Saskatchewan a été agréée, avec Bob en tant que président, encadré par une excellente équipe de la section d’ARMA. 3

ARMA – Prix et reconnaissance

En promulguant le rôle de la technologie dans la gestion des documents, Bob a remporté le premier Prix de l’informatique en 1978 pour ses efforts dans la mise en œuvre du programme de gestion des documents du gouvernement de l’Alberta. Ce prix d’excellence a été parrainé par la section ARMA d’Edmonton, et devait être présenté annuellement à la « personne méritante apportant des contributions exceptionnelles dans le domaine du traitement de l’information ». La description du prix inclut « informatique et systèmes » comme l’un des trois principaux domaines de gestion d’information et de documents de l’époque. 4

La première conférence canadienne sur la Gestion des documents a accueilli 252 participants à Banff, en Alberta, du 4 au 6 février 1980. La conférence a honoré les « Pionniers canadiens ARMA ». Bien sûr, Bob était parmi eux! Le groupe était constitué de « …présidents fondateurs de section, anciens vice-

présidents régionaux, officiels internationaux et membres fondateurs qui…sont restés actifs dans l’Arma pendant plusieurs années… Des certificats d’appréciation leur ont été décernés au Déjeuner des Pionniers, à la conférence de Banff, le 6 février 1980. » Les pionniers sont nommés et ils représentent sept sections canadiennes de l’époque : Montréal, Ottawa, Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton et Vancouver. 5

Une citation d’un des collègues de Bob, Jim Coulson, CRM, FAI, insuffle de la vie au personnage, au moment de la première Conférence canadienne: « Bob Morin, de Saskatoon, a été l’un des pionniers passionnés de CRI, qui réunit des professionnels de gestion de documents provenant des quatre coins du pays, et a organisé la première Conférence sur les documents et l’information au Canada. Deux ans plus tard, la conférence a eu lieu à Montréal, avec des présentations et des procédures dans les deux langues officielles. La conférence d’ARMA Canada est depuis lors devenue un événement annuel hautement respecté. » 6

ARMA – Publication et présentation – emblèmes de la contribution

Bob a partagé son expérience pratique avec la communauté ARMA grâce aux publications et aux présentations. Ces canaux de communication sont hautement respectés au sein de cette communauté.

Un article que Bob a écrit pour le Records Management Quarterly en 1980, intitulé « Gestion de systèmes d’information – une approche globale », montre comment l’alphabétisation informatique est un thème continu de sa carrière. L’article ne fait pas que nous informer sur les composantes technologiques de la gestion des archives de l’époque, mais souligne également l’importance de l’intégration des technologies et des disciplines: « L’approche met l’accent sur le besoin d’analyse des systèmes cléricaux dans leurs phases de conception. La rentabilité est illustrée par l’utilisation efficace de toutes les technologies de l’information telles que la micrographie, le traitement de texte, la conception de formulaires, le traitement de données et les ressources documentaires. » 7

ARMA a publié un article antérieur de Bob, datant de 1976 et intitulé « Relocating a Records Management Operation. » 8 Dans cet article, la thèse de Bob est que le gestionnaire de documents s’impliquera dans les déménagements de bureaux en raison de « son intérêt pour tous les aspects de la paperasserie ». Ces mouvements vont d’un simple réaménagement à une délocalisation complète. Il fournit un plan, étape par étape, couvrant à la fois les exigences de préparation et de déplacement physique, d’une valeur particulière pour le gestionnaire de documents. Ce sujet continue d’être d’actualité pour les gestionnaires de documents du 21e siècle!

En 1983, Bob a partagé ses connaissances lors d’une présentation à la 28e conférence annuelle, où le thème de la conférence était « L’économie émergente de l’information ». Son sujet était « Ce que le gestionnaire de documents doit savoir sur la documentation des systèmes de traitement de données ». Le synopsis indique que la présentation inclut « …la manipulation correcte des bandes magnétiques…La façon de planifier les enregistrements de traitement de données, tels que les bandes magnétiques, les bases de données et les disquettes, sera discutée. » 9

ARMA – Promotion de la formation pour les gestionnaires de documents

Une autre pierre angulaire de l’activité professionnelle de l’ARMA est la prestation de programmes de formation. Bob était aussi un leader dans ce domaine.

De 1975 à 1982, alors qu’il était directeur de la gestion des documents pour le Gouvernement de

l’Alberta, « il a dirigé un programme de formation de onze cours portant sur la gestion de documents, les systèmes de documents, la micrographie, la bureautique, la gestion de formulaires et le traitement de données… Il a enseigné la Gestion de documents à la faculté de bibliothéconomie de l’Université de l’Alberta, où il a joué un rôle déterminant dans l’établissement d’un cours crédité sur la gestion des documents. »10

Ses étudiants et ses collègues ont dit de Bob qu’il était acharné dans sa générosité pour aider les jeunes. Il a toujours soulevé le moral collectif de ceux qui l’entouraient.

En hommage, la section de l’ARMA de la Saskatchewan continue de remettre le prix Bob Morin à un jeune professionnel, pour l’aider financièrement dans le domaine de la gestion des documents.

De la liste de contrôle ARMA pour le statut professionnel, y compris les prix, l’éducation, la publication, la présentation et la sphère d’influence, Bob a souligné les grandes lignes. Pour ceux d’entre nous qui ont servi à titre de bénévoles, on peut se demander: « Où prenait-il son énergie? » Et il ne s’est pas arrêté avec ARMA!

IRMF – International Records Management Federation

En 1978, Bob a été choisi pour être l’un des deux délégués d’ARMA International à une organisation professionnelle appelée International Records Management Federation (Fédération internationale de gestion des documents) (IRMF). 11

Au départ, la Fédération a été établie pour servir un intérêt mondial pour la gestion des documents. Le Records Management Quarterly a publié une rubrique intitulée Outlook for the Federation afin de partager ses objectifs, ses motifs de fierté et ses réalisations. « La Gestion de documents n’est plus un sport entièrement américain, bien que plusieurs parmi nous “internationaux” admirent toujours ARMA – fort de plus de 4 800 membres et toujours en augmentation, et quelle équipe de gestion! » 12

En 1982, Bob avait un rôle de leadership pour le président de la Fédération.13 Un document de réflexion sur l’avenir de la Fédération a été présenté la même année à ARMA International. En conséquence, une nouvelle constitution a été examinée et approuvée par le Conseil exécutif du IRMF, qui a été renommé International Records Management Council (IRMC -Conseil International d’Administration des Archives).14 Une autre “première” pour Bob.

ICRM – Institute of Certified Records Managers

Bob a continué à assumer le leadership et à utiliser sa sphère d’influence personnelle avec l’ICRM – Institute of Certified Records Managers (Institut des gestionnaires de documents certifiés). Il a été membre du Conseil d’administration de janvier 1986 à décembre 1988.

En conclusion …

Bob est l’un des nombreux pionniers de la gestion des documents au Canada. Leur capacité d’adaptation, leur détermination et leur volonté de réussir créent un remarquable exemple d’excellence dans le domaine de la gestion des documents au Canada.

C’est un défi particulier pour ceux d’entre nous qui restent, ou qui sont nouveaux dans la profession, de faire une pause, de réfléchir sur leur parcours. Nous suivons notre propre parcours de carrière en gestion des documents – forgeant notre chemin, tout en acquérant des compétences de gestion de temps pour établir des priorités et réussir.

C’est le temps de réfléchir? Considérez cela comme des vacances professionnelles. Quelques minutes passées à retourner dans le siècle précédent vous donneront comme récompense l’inspiration et de l’admiration pour ceux qui ont fait face à des circonstances très semblables: l’influence de la société, la politique, les événements mondiaux et, toujours, le progrès de la technologie.

Bibliographie

1”Association News and Events”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Numéro 3 (1978), 51-52

2”Association News and Events”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Numéro 3 (1978), 51-52

3”Association News and Events”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 17, Numéro 3 (1983), 56 4David H. Bell, “Canadian Notes”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 13, Numéro 2 (1979), 48 5Don H. Bell, “Canadian Notes”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 14, Numéro 2 (1980), 52 6Jim Coulson, “Some Personal Reflections on the History of RIM in Canada”, 2017

7Robert P. Morin, “Management Information Systems – A Total Approach”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 14, Numéro 2 (1980) 5-6, 16

8”Records Management Quarterly Cumulative Index of Articles (Annotated) janvier 1967 – octobre 1977”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 11, Numéro 4 (1977), 63

9”28th Annual Conference ARMA The Emerging Information Economy”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 17, Numéro 3 (1983) 61

10”ICRM Information”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 19, Numéro 4 (1985), 62

11”Outlook – International Records Management Federation”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Numéro 2 (1978), 55

12Outlook – International Records Management Federation”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 12, Numéro 2 (1978), 55

13”IRMF Reorganizes: Announces New Publications”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 16, Numéro 2 (1982)

14IRMF Reorganizes: Announces New Publications”, ARMA Records Management Quarterly, 16, Numéro 2 (1982)

1ARMA Records Management Quarterly, juillet 1978 pages 51-52

2ARMA Records Management Quarterly, juillet 1978 pages 51-52

3ARMA Records Management Quarterly, juillet 1983 page 56

4ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1979 page 48

5ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1980 page 52

6Some Personal Reflections on the History of RIM in Canada, Jim Coulson, CRM, FAI

7ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1980 page 5

8ARMA Records Management Quarterly October 1977 page 63

9ARMA Records Management Quarterly, juillet 1983 page 61

10ARMA Records Management Quarterly, octobre 1985 page 62

11ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1978 page 55

12ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1978 page 55

13ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1982 page 69

14ARMA Records Management Quarterly, avril 1982 page 69

CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017 ENREGISTREMENTS ÉLECTRONIQUES UTILISÉS À TITRE DE PREUVES DOCUMENTAIRES

Par Sharon Byrch, Uta Fox, CRM, FAI et Stuart Rennie JD, MLIS, BA (Hons.)

Introduction

En mars 2017, l’Office des normes générales du Canada (ONGC) a publié la nouvelle norme sur les Enregistrements électroniques utilisés à titre de preuves documentaires, CAN/CGSB-72.34- 2017. Cette nouvelle norme annule et remplace la version de 2005, CGSB 72.34-2005. Deux des auteurs de cet article, Uta Fox et Stuart Rennie, étaient membres du comité de l’ONGC qui a élaboré la CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017. Ayant co-présenté les deux versions de la norme CAN/CGSB-

- dans les conférences nationales d’ARMA Canada et dans les sections d’ARMA Canada à travers le pays, ils sont fréquemment contactés afin de fournir plus d’informations sur cette norme. Cet article répond à ces demandes d’informations de la communauté de gestion des documents (GD) sur la mise à jour de 2017, et sur comment l’appliquer.

Afin d’élargir la portée de cet article, ils ont abordé Sharon Byrch, professionnelle de la GD, qui a accepté de collaborer à sa rédaction. Il traite des différences majeures amenées par la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 comparativement à la version de 2005, du point de vue juridique, de gestion des documents (GD) et des technologies de l’information (TI). Bien que l’accent soit mis principalement sur les changements importants au contenu, il contient certaines recommandations pour la mise en œuvre de la norme dans vos programmes de gestion des documents et de gouvernance de l’information (GI).

Dans cet article, les opinions exprimées par les auteurs sont personnelles et ne sont affiliées à aucun organisme. Les informations fournies sont basées sur leurs expériences et sur les connaissances qu’ils ont acquises, et sont uniquement partagées à titre informationnel, et non dans le but de fournir des conseils juridiques, techniques ou professionnels.

L’objectif de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 est de suggérer des principes et des procédures que les organismes peuvent appliquer afin d’améliorer l’admissibilité de leurs enregistrements électroniques à titre de preuve dans les procédures judiciaires. La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 est une norme volontaire, disponible à l’achat en français et en anglais, et peut être obtenue en format papier ou en version électronique. La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 ne remplace pas les conseils juridiques et techniques d’experts.

L’ONGC est un organisme du gouvernement fédéral canadien qui aide à l’élaboration de normes dans de nombreuses industries. Actuellement, il y a plus de 300 normes à l’ONGC. Ces normes sont élaborées par un comité de bénévoles, experts dans leurs domaines respectifs. L’ONGC est accrédité par le Conseil canadien des Normes (CCN), une société d’état fédérale, à titre d’organisme d’élaboration de normes. Son mandat est de promouvoir des normalisations efficientes et efficaces au Canada. La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 est une norme nationale du Canada, comme en témoigne l’inclusion du préfixe «CAN» dans son numéro de référence, ce qui indique qu’elle est reconnue comme norme canadienne officielle dans un domaine particulier. 1

Lors de la lecture de la norme, les utilisateurs doivent être attentifs au langage utilisé par l’ONGC pour que les organismes puissent se conformer à la norme. Prenez le mot « doit » par exemple, souvent utilisé dans CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017. “Doit” implique des exigences obligatoires. Par exemple, “Un organisme doit établir le programme de GD”.2 Ceci est une déclaration d’obligation. Autrement dit, les organismes qui utilisent cette norme doivent avoir en place un programme de GD autorisé. Le mot « devrait » indique une recommandation tandis que « peut » correspond à une option, ou ce qui est permis dans les limites de la présente norme.

En plus de démontrer l’intégrité, l’authenticité et la fiabilité des enregistrements électroniques afin de répondre aux exigences en matière de preuve, les organismes doivent s’assurer que les enregistrements électroniques qu’ils créent, reçoivent et conservent dans les systèmes de tenue d’enregistrements électroniques sont conformes aux exigences du CAN/CGSB-72.34- 2017, afin d’assurer leur admissibilité dans les instances judiciaires. Comme indiqué:

Cette norme fournit un cadre et des lignes directrices pour la mise en œuvre et l’exploitation des systèmes de dossiers pour les enregistrements électroniques, que les renseignements qu’ils contiennent soient ou non éventuellement requis à titre de preuve. Ainsi, le respect de cette norme doit être considéré comme une démonstration de gestion responsable des affaires.

L’application de la norme aux procédures d’un organisme n’éliminera pas la possibilité de litiges, mais il est fort probable que cela rendra la production d’enregistrements électroniques plus faciles et leur acceptation dans une procédure juridique plus certaine.3

L’un des changements apportés grâce à la mise à jour CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 est que l’ONGC a retiré une norme complémentaire : CAN/CGSB-72.11-93 Microfilms et images électroniques à titre de preuve documentaire. Ce retrait est entré en vigueur le 24 janvier 2017.4 Le raisonnement qui a mené au retrait de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.11-93 est dû à son utilisation limitée et à l’appui général au sujet de sa révision. De plus, la section 3 de la partie III et la section 3 de la partie IV, traitant des images électroniques dans la norme CAN/CGSB 72.11-93, sont incorporées dans la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017. Les organismes peuvent toujours utiliser et référencer CAN/CGSB-72.11-93, mais cela n’est pas recommandé, puisqu’elle n’a plus de poids et n’est plus appuyée par l’ONGC. Par conséquent, les organismes devraient utiliser la version la plus récente de la norme, la CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017.

Exigences juridiques relatives aux enregistrements électroniques à titre de preuves documentaires

La section 5 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 détermine les exigences juridiques applicables aux enregistrements électroniques à titre de preuve documentaire.

Comme la version 2005, la nouvelle norme 2017 se concentre sur ces exigences juridiques en matière de recevabilité juridique:

[L ‘] utilisation d’un enregistrement électronique à titre de preuve exige la démonstration de l’authenticité de l’enregistrement, qui peut être faite en démontrant l’intégrité du système de dossiers électroniques dans lequel l’enregistrement est fait ou reçu ou stocké, et en démontrant que l’enregistrement a été fait “dans le cours normal des affaires” ou est par ailleurs exempté de la règle juridique interdisant le ouï-dire. 5

Il en résulte que les versions 2017 et 2005 sont essentiellement les mêmes, afin que les organismes utilisant la norme de 2005 puissent modifier leurs politiques, procédures et flux de travail pour se conformer à la nouvelle norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 sans avoir à recommencer. Ce qui est pratique.

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 fait constamment référence à la Loi sur la preuve au Canada et ne mentionne pas les lois provinciales ou territoriales. Les organismes qui ne sont pas assujettis à la juridiction fédérale canadienne devront examiner la loi provinciale ou territoriale qui s’applique à eux, au sujet de leurs enregistrements électroniques.

De plus, les organismes peuvent utiliser d’autres sources d’informations juridiques pour comprendre comment les cours et tribunaux du Canada interprètent ces exigences juridiques. Une source d’information utile à ce sujet est le site Web de l’Institut canadien d’information juridique: https://www.canlii.org/. CanLII, un organisme non gouvernemental à but non lucratif, offre en ligne un accès gratuit à des jugements de tribunaux, décisions judiciaires, lois et règlements provenant de toutes les provinces et de tous les territoires du Canada, avec une interface de recherche facile à utiliser. L’information juridique est disponible en anglais et en français. CanLII est l’une des meilleures sources d’information pour les avocats, ainsi que le grand public, pour consulter la loi canadienne.

La section5 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 souligne à juste titre que les organismes doivent prouver que leurs enregistrements électroniques sont juridiquement admissibles. Deux outils clés pour la preuve que les organismes peuvent utiliser sont: (1) Manuel de GD (2) Guide de gestion du système informatique. Ces outils devraient contenir les politiques et procédures autorisées de l’organisme servant à fournir les preuves documentaires que celui-ci satisfait les exigences en matière d’admissibilité juridique de ses enregistrements électroniques.

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 comporte de nouveaux éléments pour refléter les changements technologiques depuis 2005:

- Découverte électronique (preuve électronique);

- Révision assistée par la technologie (RAT) utilisant un logiciel spécifique de recherche;

- Mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques; et

- Signatures électroniques et

Découverte électronique (preuve électronique) et préparation aux litiges

Dans la section 5.3, pour la première fois, CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 fait référence à la découverte électronique au cours de litiges civils. La découverte électronique est une procédure préalable au procès, où les parties en litige sont tenues d’échanger les enregistrements électroniques pertinents, sous la supervision des tribunaux. Puisque les organismes créent et enregistrent maintenant des enregistrements électroniques en plus grand nombre, leur défi est de pouvoir rechercher, consulter et produire les enregistrements électroniques pertinents requis par les tribunaux canadiens, afin qu’ils puissent être admissibles à titre de preuve dans les procédures judiciaires.

En 2008, pour aider les organismes à la production d’enregistrements électroniques admissibles au Canada, les Principes de Sedona Canada portant sur la découverte électronique (Principes de Sedona Canada) ont été élaborés. Sedona Canada est une organisation bénévole non gouvernementale regroupant avocats, juges et technologues à travers le Canada. Les Principes de Sedona Canada sont en grande partie une norme volontaire, comme l’ONGC, sauf en Ontario. Depuis 2010, les principes de Sedona Canada sont obligatoirement utilisés dans les tribunaux de l’Ontario, en vertu des Règles de procédure civile de la province. À l’extérieur de l’Ontario, les principes de Sedona Canada sont acceptés dans les cours et les tribunaux du pays pour aider les parties à produire et à consulter les enregistrements électroniques pertinents, en temps opportun et de manière efficace et économique. À l’heure actuelle, il existe une jurisprudence canadienne en cours de développement en matière de Principes de Sedona Canada.

En 2015, à l’instar des changements apportés par l’ONGC en 2017 à la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34- 2005, Sedona Canada, pour tenir compte des changements dans les domaines technologiques et juridiques, a publié une deuxième édition mise à jour des Principes de Sedona Canada.6

En ce qui concerne la divulgation dans les procédures pénales, le CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 est référé, pour la première fois, dans R. c. Oler, 2014 ABPC 130 (CanLII).7 L’affaire Oler est un cas majeur pour plusieurs raisons. Premièrement, Oler est la première instance à considérer et à appliquer la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34 de 2005. Deuxièmement, Oler est aussi le premier cas au Canada à soutenir que le processus de numérisation d’un organisme est admissible à titre de preuve électronique, parce qu’il est conforme à la Loi sur la preuve au Canada, et à l’Alberta Evidence Act pour son utilisation des standards industriels. Troisièmement, le tribunal dans

l’affaire Oler est le premier au Canada à accepter la preuve d’expert en gestion des dossiers. L’expert dans l’affaire Oler était Uta Fox, co-auteure de cet article. Uta Fox est la première gestionnaire de GD reconnue au Canada pour avoir été acceptée à titre de témoin expert juridique qualifiée. À ce titre, elle a aidé le tribunal à déterminer l’admissibilité juridique d’enregistrements électroniques.

Il existe peu de jurisprudences au Canada sur la relation entre la GD et la loi. Il en faut plus, afin de faire progresser la profession de gestion des documents électroniques et de l’information, ainsi que l’admissibilité des documents, en particulier les enregistrements électroniques, dans les tribunaux canadiens. Cette situation devient d’autant plus critique au fur et à mesure que les organismes deviennent de plus en plus « numériques » et ne créent et gèrent que des enregistrements électroniques, et non des documents papier. Compte tenu de la prédilection des tribunaux canadiens à faire référence à des Normes nationales du Canada approuvées, telle que CAN/CGSB-72.34-20, l’affaire Oler est un pas dans la bonne direction pour la gestion des documents électroniques et de l’information.

Il est de plus en plus nécessaire que les professionnels de la GD soient acceptés devant les tribunaux en tant qu’experts, comme Uta Fox l’a été, pour les aider à déterminer l’admissibilité de la preuve électronique. Les tribunaux canadiens ne qualifient pas les personnes d’experts à la légère. Ils exigent des preuves démontrant qu’une personne possède les qualifications, la formation, les connaissances spécialisées et l’expertise nécessaires pour être qualifiées d’expert. De plus, la personne doit être indépendante et impartiale pour assister le tribunal en tant qu’expert.8 Les organismes qui, à l’instar du Service de police de Calgary dans l’affaire Oler, utilisent des systèmes de gestion des enregistrements électroniques et des documents et des dossiers (SGEDD), exploitent et gèrent des systèmes complexes de GD et de TI, avec des répercussions juridiques dépassant l’expérience du public ou de l’utilisateur occasionnel. Alors que de plus en plus d’organismes passent au SGEDD, il doit y avoir plus d’experts de GD attitrés par les tribunaux pour conseiller sur ces systèmes complexes, afin de déterminer l’admissibilité de leurs enregistrements électroniques dans les affaires civiles et criminelles. Oler est la première affaire au Canada qui autorise l’admissibilité des enregistrements électroniques numérisés à l’aide d’un SGDDE, à la place d’originaux sur papier. Nous devons développer la jurisprudence en matière de GD pour suivre le rythme de l’utilisation des SGDDE en affaires.

D’un point de vue juridique, ce sont des ajouts favorables à la norme. Les organismes peuvent se référer aux Principes de Sedona Canada et à l’affaire Oler, en plus de la norme CGSB 72.34- 2017, comme sources d’information sur les meilleures pratiques crédibles afin d’améliorer encore davantage la conformité juridique de l’organisme, et réduire ses risques juridiques.

Revue assistée par la technologie (RAT) et autres outils et techniques automatisés

La norme de 2005 est muette sur la revue assistée par la technologie. Elle est abordée pour la première fois dans la section 5.3.1 de CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017. La revue assistée utilise la technologie pour automatiser le processus d’identification des enregistrements électroniques pertinents. Comme la preuve électronique, CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 fait référence aux Principes de Sedona Canada, et avec raison. Les organismes utilisent de plus en plus la revue assistée par la technologie, et la jurisprudence canadienne y fait référence, ce qui en fait un autre ajout favorable.

Mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques

La section 5.4 de CAN/ONGC-72,34-2017 fait référence à une « mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques », qui était absente de la norme de 2005. De plus en plus appliquée à tous les dossiers, une mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques est un processus où un organisme conserve toute forme de document potentiellement pertinent lorsque le litige est raisonnablement prévu, ou en cours. Le risque encouru par un organisme pour ne pas avoir préservé les preuves électroniques sous une mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques est que des preuves pertinentes soient détruites par inadvertance, et donc indisponibles aux tribunaux pour déterminer la responsabilité ou la décharge. Quand un organisme détruit par inadvertance des preuves importantes, cela augmente son risque d’avoir à subir des sanctions juridiques par les tribunaux, qui sont mécontents lorsqu’il y a destruction de la preuve, car cela pourrait servir à subvertir la primauté du droit.

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 fait référence aux Principes de Sedona Canada concernant les mises en suspens pour des raisons juridiques. Ensemble, la CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 et les Principes de Sedona Canada permettent aux organismes de bien comprendre ce qu’il faut conserver, comment l’appliquer et comment éviter le risque de détruire ou de spolier par inadvertance des preuves électroniques pertinentes. Les deux normes soulignent le besoin de conseils juridiques d’experts dès que possible lorsqu’une mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques s’avère nécessaire.

Signatures

Pour ce qui est des signatures, la norme de 2005 ne comporte pas de section spécifique pour les signatures électroniques et papier, elle ne fait que les mentionner au passage.

Quant à la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017, elle consacre la section 5.5 aux signatures électroniques et manuscrites. Une signature manuscrite est généralement faite en encre, avec un sceau de papier ou même avec de la cire traditionnelle. La distinction entre les signatures électroniques et manuscrites est utile. De nombreux organismes utilisent aujourd’hui simultanément les deux types de signatures; il y a souvent confusion et incertitude au sein même des organismes quant à l’admissibilité juridique de ces deux signatures. La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 fournit les exigences de base pour leur utilisation, et spécifie quand demander l’avis d’un expert pour assurer leur admissibilité juridique.

Copies papier authentifiées pour les procédures judiciaires (« copies certifiées »)

Pour les « copies certifiées », la norme de 2005 de la section 5.6 exigeait que les copies papier soient authentifiées comme une « copie certifiée » de l’original, avec une signature pour améliorer sa recevabilité et son importance devant les tribunaux. Cette authentification devait être documentée avec des procédures.

Dans la version 2017, la section 5.6 est énoncée essentiellement comme la norme de 2005. La principale différence est que la norme de 2005 ne mentionne pas les « dossiers électroniques », ils sont implicites; la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017, quant à elle, utilise l’expression « enregistrements électroniques » pour préciser que les copies d’enregistrements électroniques doivent être authentifiées par signature comme étant des « copies certifiées » des enregistrements électroniques.

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 ajoute également qu’un affidavit peut être utilisé comme enregistrement d’authentification; la norme de 2005 ne mentionne pas l’affidavit. La nouvelle référence à l’utilisation d’un affidavit est utile, puisque c’est un outil usuel de preuve dans le processus de litige.

Programme de Gestion des documents (GD)

Les deux versions de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34 contiennent des dispositions sur l’établissement d’un programme de GD. La version 2005, intitulée « Création d’un système de GD » a été modifiée en 2017 pour devenir « Programme de gestion des documents d’archives ».

Avant de discuter des changements à la GD dans la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017, passons en revue ce qui est reporté de la norme de 2005, puisque ce sont des éléments essentiels pour votre programme de GD. Les sections 6.1 à 6.4.1 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 traitent des éléments fondamentaux qu’un organisme doit posséder en ce qui concerne: les concepts de GD, principes, méthodes et pratiques adoptés par l’organisme doivent démontrer qu’un programme de GD approprié est en place et fait partie intégrante du processus habituel et normal des activités de l’organisme en question.9

Par conséquent, les organismes doivent avoir :

- Un programme de GD autorisé;

- Une politique de GD autorisée;

- Un manuel de GD autorisé; et

- Un archiviste.10

À la section 6.1, il est mentionné que le programme de gestion des documents lui-même « doit prendre en charge un système de dossiers composé de procédures et de contrôles des dossiers appropriés qui complémentent les procédures opérationnelles de l’entreprise. »11 Un organisme doit:

- Établir le programme de GD;

- Élaborer une politique de GD, avec des définitions et des attributions de responsabilités;

- Concevoir des procédures de GD avec sa documentation connexe;

- Sélectionner et mettre en œuvre des technologies soutenant le système de GD;

- Établir des mesures de protection des documents, y compris des pistes de vérification et de sauvegarde; et

- Établir un processus d’assurance qualité des documents.12

Remarquez, ces déclarations sont des déclarations “doit”; ce qui signifie que l’organisme doit soutenir les systèmes de GD en utilisant des procédures d’enregistrement et des contrôles appropriés en harmonie avec les opérations commerciales.

Les organismes doivent établir un programme de GD, avoir une politique GD, utiliser des définitions, attribuer des responsabilités, élaborer des procédures, sélectionner des technologies, mettre en œuvre des processus de protection des documents et adopter un programme d’assurance qualité. Ce sont des facteurs non négociables qui doivent être en place avant même que l’organisme puisse commencer à se conformer à cette norme.

Responsabilité – Archiviste

Les deux versions, soit celle de 2005 et de 2017 du CAN/ONGC72.34, imposent aux organismes de nommer un archiviste, qui sera responsable de la mise en œuvre du programme de GD, et qui assurera son intégration aux activités régulières de l’organisme. De plus, l’archiviste est responsable de certifier que l’organisme met en œuvre la politique, le programme, et le manuel de GD. Le rôle et les responsabilités de l’archiviste doivent être définis dans une politique, un règlement ou une directive, car son rôle est essentiel à l’établissement et au maintien du programme de GD, et à la supervision de la conformité de l’organisme aux lois, normes et politiques ayant un impact sur le programme.

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 fournit des directives à l’archiviste en reconnaissant que la politique de l’organisme lui confère la responsabilité de maintenir et de modifier «…le manuel de GD, avec le soutien du personnel de TI, afin qu’il reflète l’état exact des documents d’archives et puisse constituer une preuve de la conformité du système avec la loi et cette norme.»13 Les responsabilités des employés ayant des fonctions de GD doivent également être définies à des fins de vérification de conformité. Cette directive s’applique à tous les employés d’un organisme qui ont des fonctions de GD, pas seulement les employés du département de GD. Afin de se conformer à la norme CGSB 72.34-2017, assurez-vous que votre organisme remplisse les exigences et les devoirs de la GD pour tous vos employés.

Politique de GD

Les deux versions de l’ONGC soulignent que la haute direction doit autoriser une politique de GD qui stipule que la gestion des enregistrements électroniques fait partie intégrante du cours normal des activités de l’organisme. De plus, la politique doit identifier et élaborer sur:

- Les dossiers applicables, systèmes de dossiers et exclusions (portée);

- Les normes pertinentes de GD et de la technologie de l’information, utilisées dans les programmes de GD;

- La responsabilité de l’archiviste pour le système de dossiers;

- La conformité du système de dossiers avec le manuel de GD, la loi, les normes nationales, internationales et industrielles;

- La responsabilité de l’archiviste quant au maintien et la mise à jour du manuel de GD;

- Les exigences relatives à la création, à la gestion, à l’utilisation et à la disposition des documents;

- Le travail conjoint du département informatique avec l’archiviste pour intégrer la GD dans le processus habituel des affaires; et

- Les processus de l’assurance qualité sont attribués à l’archiviste.14

Manuel de GD

Le manuel de GD est l’outil qui sert à regrouper toutes les procédures liées aux documents, afin d’assurer l’exhaustivité et la cohérence de la pratique15, et qui sont incluses dans les deux versions de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34. Les composants requis d’un manuel de GD, par exemple les procédures pour faire, recevoir, sauvegarder et supprimer des documents, sont également cohérents entre les versions. CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 souligne que le manuel de GD:

devra être tenu à jour et refléter avec précision la nature exacte, les fonctions, procédures et processus du système électronique de l’organisme, c’est-à-dire la façon dont ce système participe et soutient le processus habituel des affaires;16

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 indique que le manuel doit spécifier le fonctionnement et l’utilisation des systèmes électroniques et inclure des références à d’autres documents pertinents, par exemple le Guide de gestion du système des TI, les procédures opérationnelles ou la documentation du système des TI.17 Voilà un autre exemple de la norme contraignant les TI et la GD à collaborer pour se conformer aux exigences.

Alors que la GD communique ses exigences différemment des TI, il est clair que ces deux domaines ont des intérêts communs et le même but final: une meilleure gouvernance de l’information à propos de la gestion des dossiers électroniques. Il est tout à fait stratégique pour la GD et les TI de collaborer, car supporter un domaine fait avancer les buts et les objectifs de l’autre et, finalement, les deux en bénéficient. Les TI et la GD sont essentiellement des expressions différentes d’un même objectif. Vos parties prenantes se superposent en partie, vous partagez les mêmes risques et conséquences, ressources et priorités.

Le futur de la GD dépend de son implémentation et intégration réussie, à l’intérieur même d’un organisme. Les rouages internes entre la GD et les TI sont décisifs pour cette réussite, et elle ne dépend que de l’implication des deux parties dans cette méthodologie stratégique. Le plus tôt cette coopération de travail, ce développement de ressources, cette communication et assistance pour faire avancer le travail est établie, le mieux cela sera.

Garder le manuel à jour, en utilisant un processus d’examen formel à des moments prédéterminés, garantis que le manuel de GD continue de refléter les activités de GD pour les enregistrements électroniques, en temps réel.18

Votre politique, votre programme, votre manuel et votre archiviste combinés forment les assises et les aspects fondamentaux de vos opérations de GD. Les organismes ne sont pas conformes à la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 s’ils ne disposent pas d’une politique, d’un programme, d’un manuel ou d’un archiviste et qu’ils sont appelés à produire leurs dossiers électroniques à des fins judiciaires. Comme l’indique la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017, le respect de cette norme « devrait être considéré comme une démonstration de la gestion responsable des affaires ».19

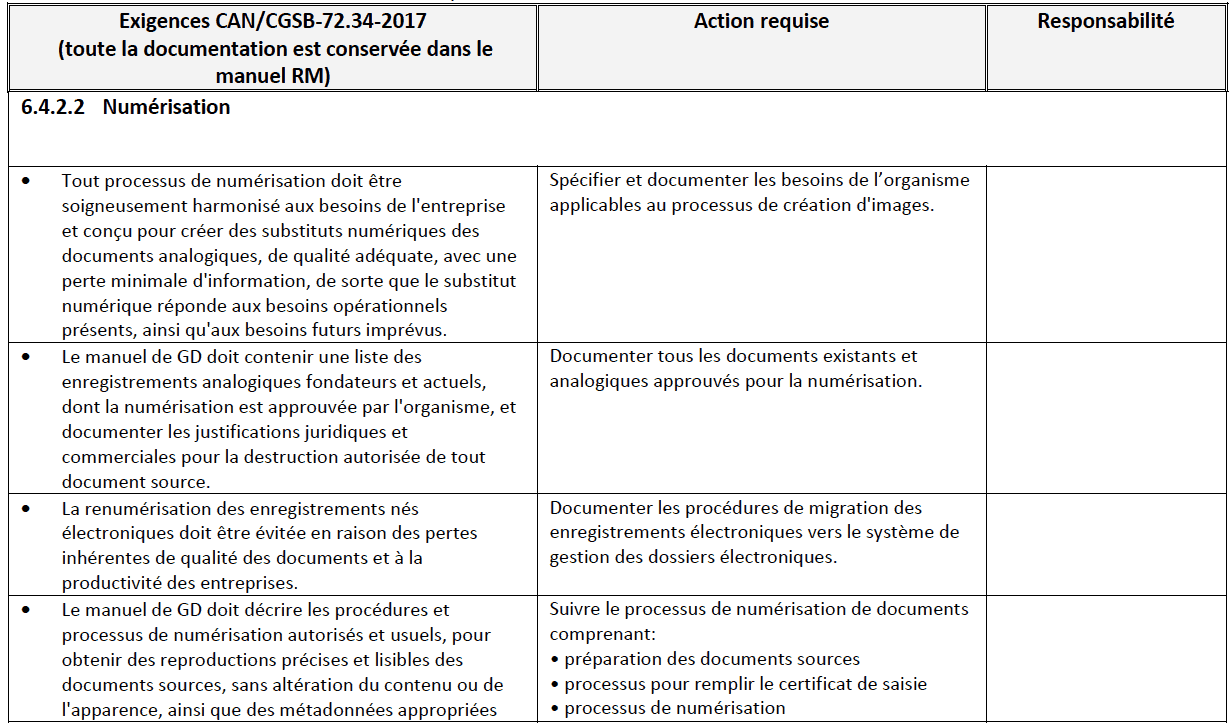

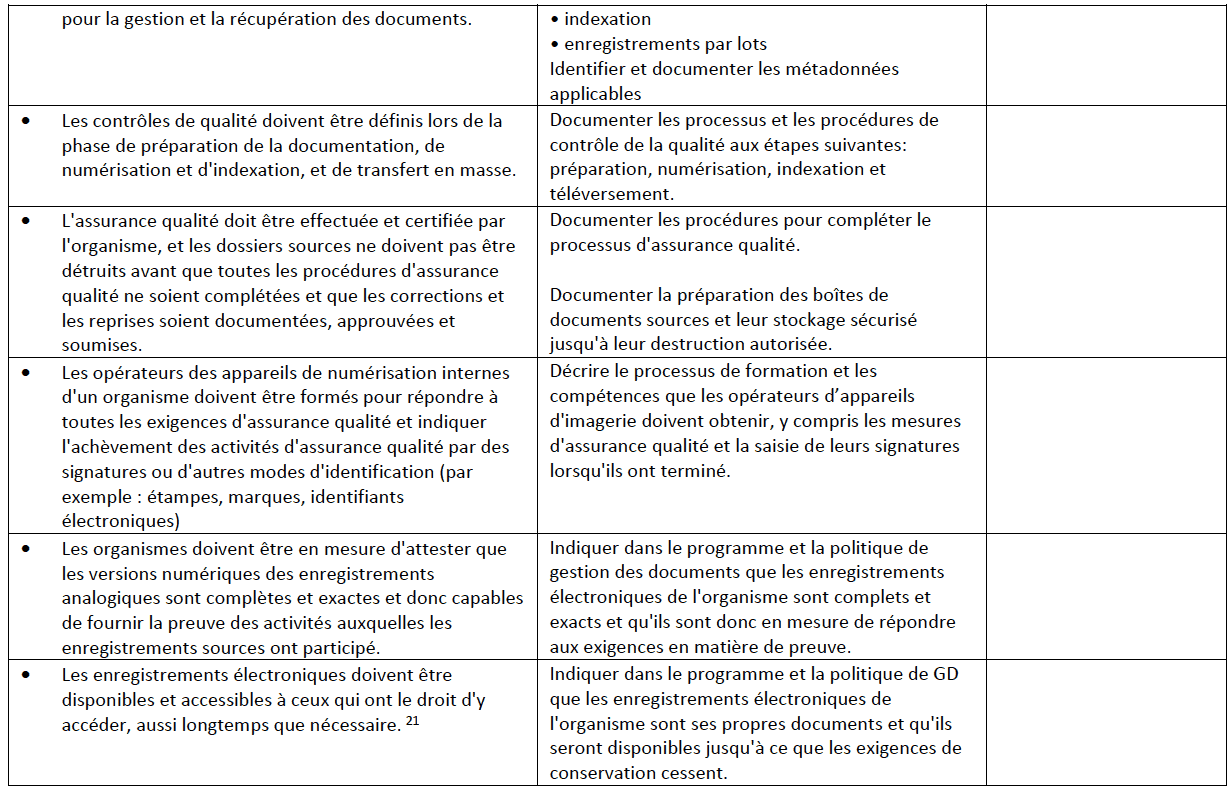

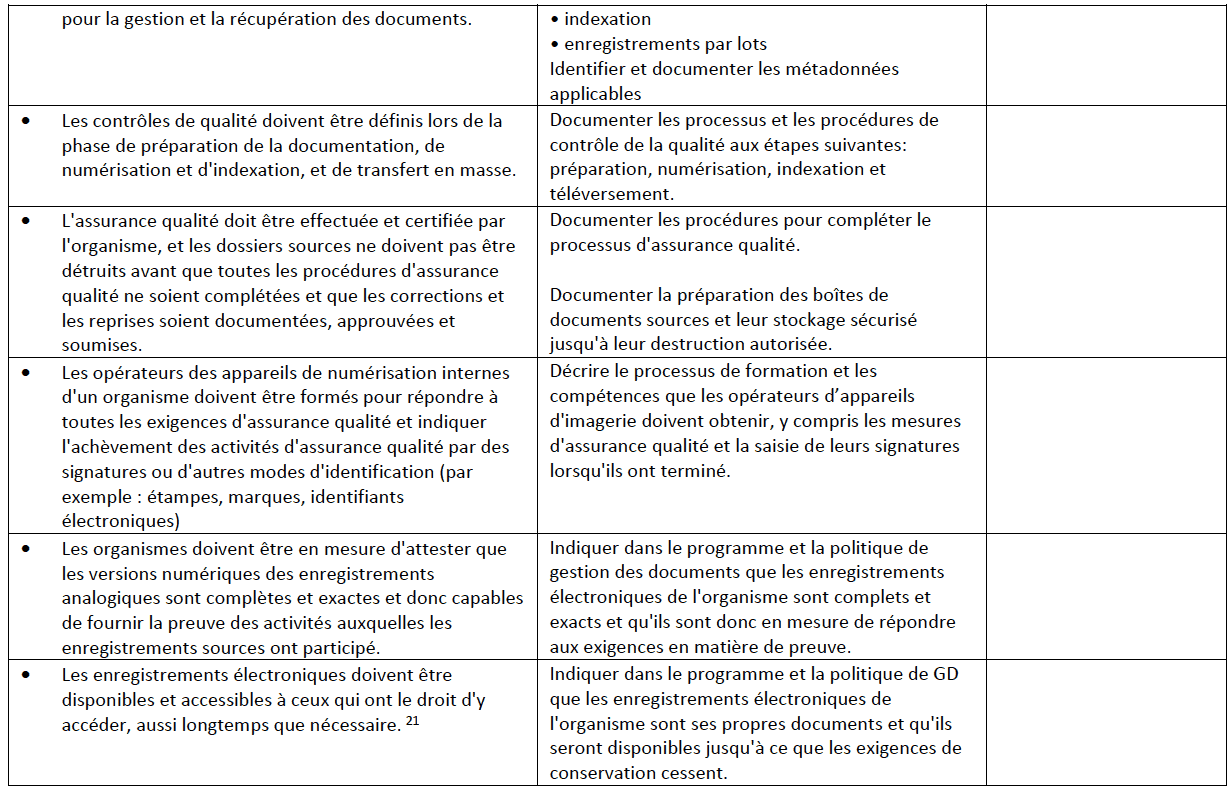

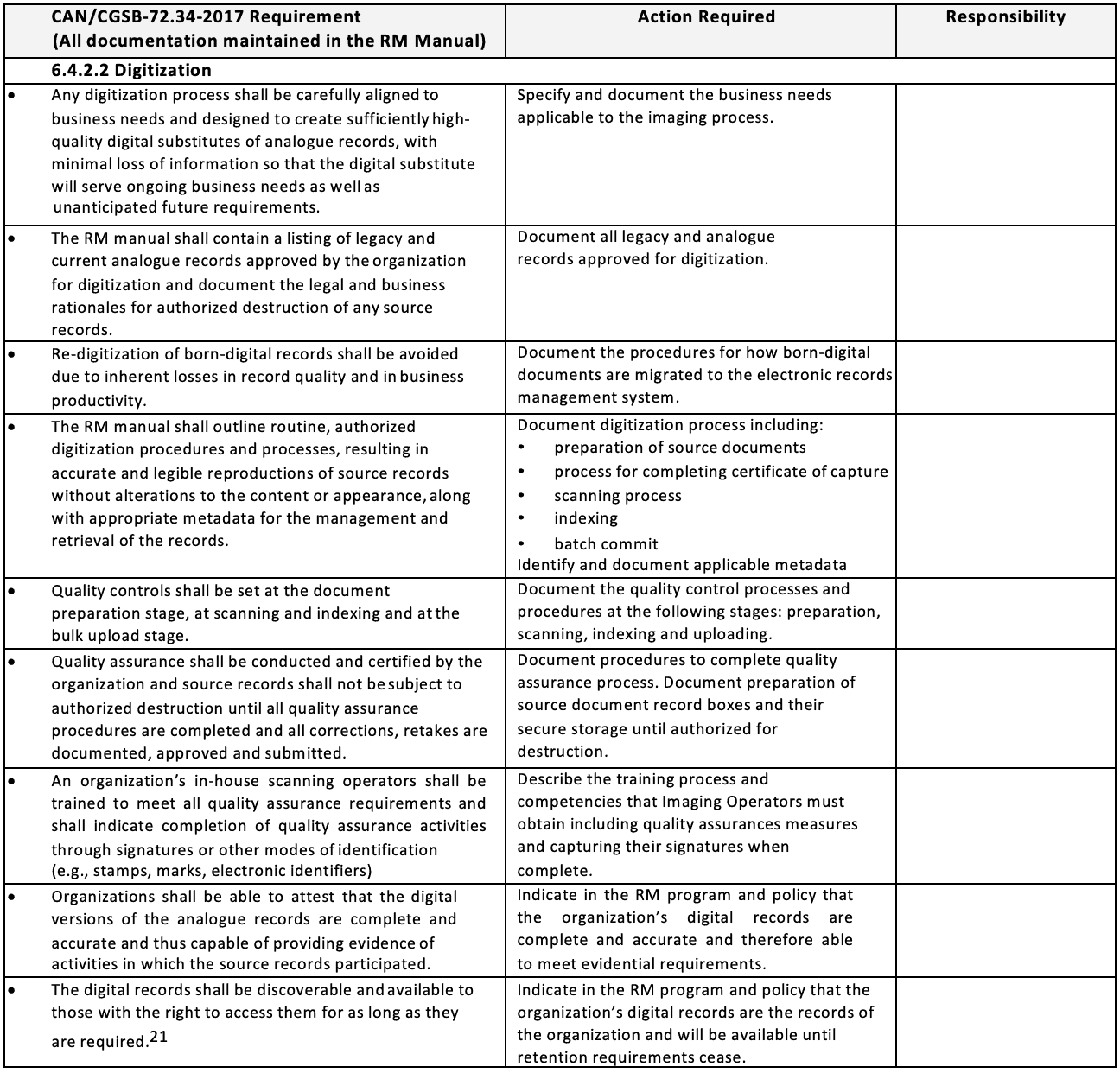

Numérisation

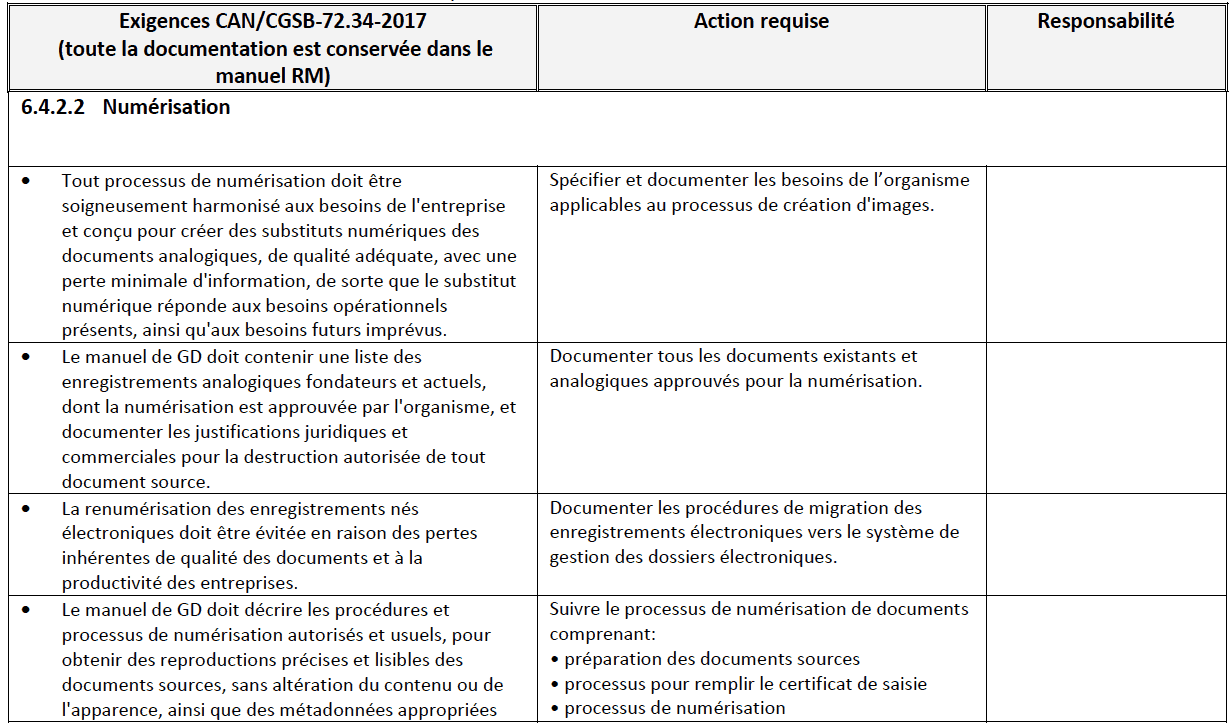

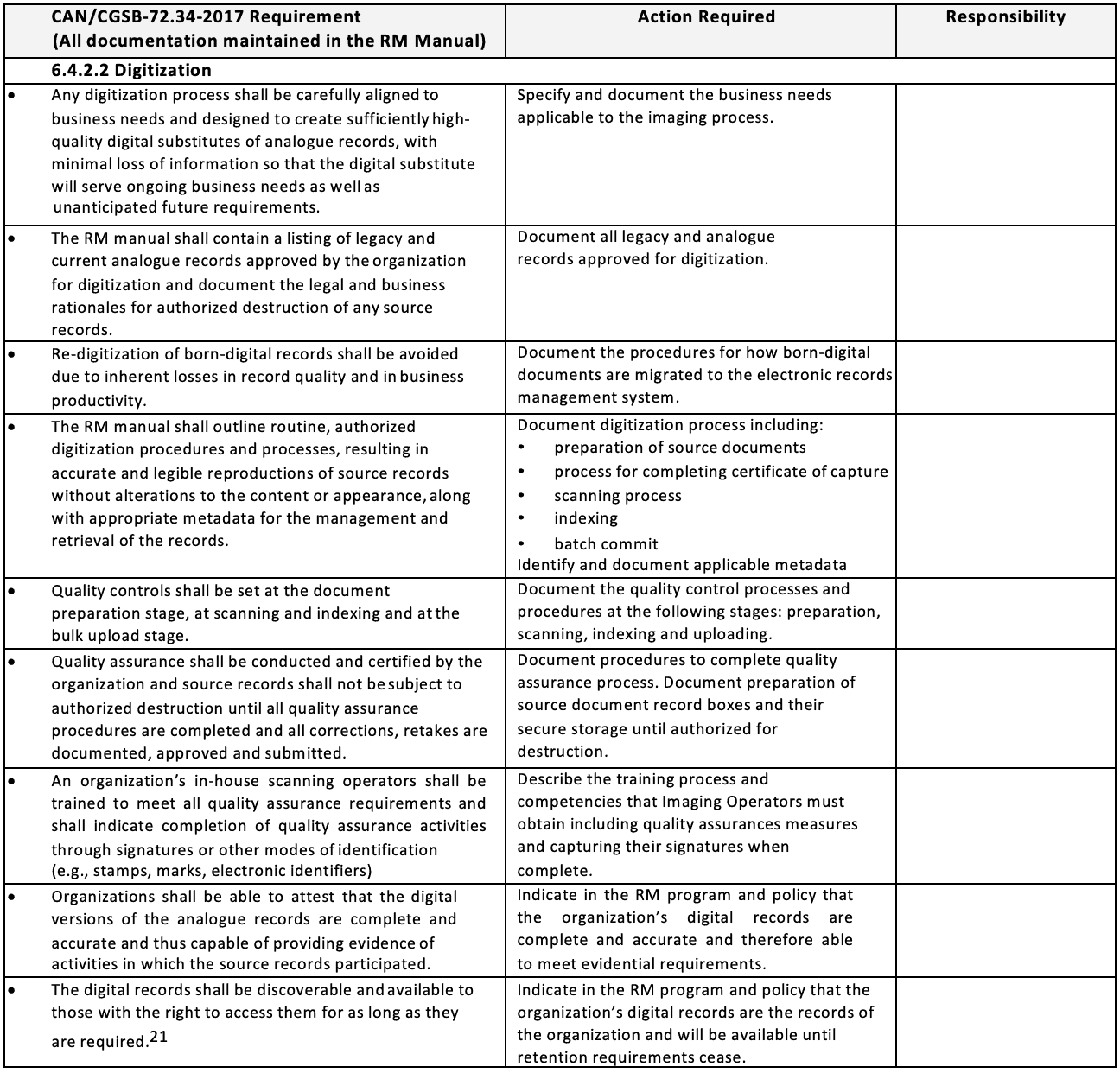

Tel qu’indiqué à la page 3, la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 incorpore les éléments fondamentaux de Microfilms et images électroniques comme preuve documentaire (CAN/CGSB- 72.34-11-93) requis pour la numérisation. Les organismes qui mettent en œuvre un programme d’imagerie dans leurs programmes de GD peuvent utiliser la liste de contrôle suivante qui énumère les exigences de CAN/CGSB-72.34-201720, décrites dans le Tableau I ci-dessous. Les organismes ayant un programme d’imagerie existant peuvent aussi utiliser cette liste de contrôle comme outil de vérification pour démontrer leur conformité à la norme CAN/CGSB- 72.34-2017.

Cette liste de contrôle fournit les exigences « doit », directement prises de la norme (voir la colonne « Exigences CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 » ci-dessous). Elle mentionne également les exigences qui doivent être adressées et appliquées, avec la colonne “Action requise”. Enfin, la colonne “Responsabilité” détaillera les postes responsables de la réalisation des actions. Cette liste de contrôle ne contient que des suggestions, et il est fortement recommandé de développer un système de suivi quelconque afin de documenter l’état de l’implémentation et son progrès.

Tableau I

Liste de contrôle pour la numérisation – 6.4.4.4 Numérisations

Exigences de conservation des dossiers

Un certain nombre de modifications ont été apportées à la section sur la conservation des documents dans la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017. La version de 2005 traitait des exigences en matière de consommation, de biens et de services lors de l’attribution de périodes de conservation, tandis que la version de 2017 adopte une approche commerciale générale. La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 stipule que pour attribuer des périodes de conservation appropriées, les personnes autorisées responsables des fonctions organisationnelles prises en charge par les documents (par exemple, représentation juridique, finances, RH) doivent être incluses dans les décisions d’évaluation et de conservation. Idéalement, les organismes devraient établir un comité de gestion des documents, composé d’experts en la matière, du juridique, de la finance, des ressources humaines et autres responsables, de ces décisions. Les décisions prises par le comité d’autorisation attribuant les périodes de conservation pour les séries de documents doivent être documentées dans le cadre du calendrier de conservation des documents, et liées au système de classification.

La norme fournit plusieurs facteurs critiques d’évaluation qui peuvent ultimement définir les exigences de rétention, notamment:

- Comment l’organisme utilise les documents, à l’interne et à l’externe;

- Le besoin d’accès des utilisateurs en cas de sinistre;

- La valeur financière, juridique, sociale, politique et historique des documents;

- Analyse coûts/avantages de la rétention;

- Impact sur l’organisme si les documents sont détruits; et

- La valeur probante des dossiers si nécessaires pour un litige, un audit ou une enquête.22

Les autres changements apportés à la norme de 2017 portent sur le système de dossiers de l’organisme et sur sa capacité à tenir compte des conservations à date d’échéance fixe, par date d’événement et permanente. L’archiviste doit examiner toutes les dispositions relatives aux dossiers avant qu’une décision de destruction ne soit prise afin de s’assurer que les documents dont l’élimination est prévue ne sont pas assujettis à une mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques, ou un contrôle organisationnel ou gouvernemental.23 Si tel est le cas, les documents doivent être suspendus du processus de destruction, tel que décrit à la section 5.4 Mise en suspens pour des raisons juridiques de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017.

Disposition des documents

Il y a des changements importants à la section sur la disposition dans la norme CAN/CGSB- 72.34-2017. La version de 2005 reconnaissait la disposition qui comprenait la destruction des documents et le transfert à une autre entité, mais il n’y avait pas de discussion sur le transfert des documents à un autre organisme ou sur la conservation des dossiers.

La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 rectifie cette situation en fournissant des détails substantiels sur le processus de disposition, la destruction des enregistrements électroniques, le transfert des documents à une autre entité et les pratiques de préservation des dossiers conservés de façon permanente ou à long terme.

Destruction d’enregistrements électroniques

Tel que mentionné, les deux versions de la norme reconnaissent que les documents doivent d’abord répondre aux exigences de conservation et être autorisées à être éliminées/détruites avant de commencer toute action de disposition. La norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 précise que le manuel GD doit permettre au système d’enregistrement de détruire, de modifier ou de corriger les documents, à l’aide d’un processus modifiable. Quant aux documents qui ont été détruits, les procédures du système doivent assurer que le document, ainsi que son localisateur, sont détruits. Il stipule également que la destruction des documents doit être complétée de manière à ne pas compromettre la confidentialité et la protection des renseignements personnels.24

Transfert d’enregistrements électroniques à une autre entité

Dans la section 6.4.6.4 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017, il est stipulé que le manuel GD d’un organisme doit documenter tous les documents transférés et acceptés par les archives (ou une autre entité), et que l’organisme qui transfère les documents et celui qui les reçoit doivent maintenir cette documentation. L’organisme destinataire peut exiger des informations supplémentaires telles que: l’identité du matériel et des logiciels qui ont généré les enregistrements, la documentation du programme décrivant le format, les codes de fichier, la disposition des fichiers et autres détails techniques du système de documents dans lequel les documents résidaient.25

Conservation des documents

La section 6.4.6.5 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 reconnaît que les organismes doivent s’assurer que leurs manuels de GD insistent sur le fait que la conservation des documents débute avec la création et la conservation des documents en formats de fichiers conservables, qui enregistrent les métadonnées d’identité et de tenue de documents requis. Tout au long du cycle de vie des documents, les organismes doivent démontrer que les enregistrements électroniques ont été créés, reçus et conservés dans le cours normal de leurs affaires et continuent de répondre aux exigences d’admissibilité en assurant leur authenticité.

Les organismes tenus de conserver des documents de manière permanente doivent s’assurer que leurs systèmes de tenue de documents sont capables de tenir en permanence des registres

– surtout à considérer lors de la sélection des systèmes de dossiers, tout comme la protection des documents contre l’obsolescence de logiciels.26

Conversion des documents et migration

La section 6.4.6.5.2 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 décrit la conversion des documents comme étant le changement d’informations enregistrées d’un format à un autre, tandis que la migration est le déplacement d’informations enregistrées d’un système des TI à un autre (les deux sont des méthodes d’éviter l’obsolescence des programmes, et les deux comportent des risques). La norme dénote qu’il y a deux types d’obsolescence :

- L’obsolescence des formats de fichiers – lorsque le programme ne peut ouvrir ou visionner le contenu du document. L’obsolescence des formats de fichiers peut être évitée par la conversion des documents ou le déplacement d’un document d’un format à un autre;

- L’obsolescence des systèmes – lorsqu’un système ou une application n’est plus supporté et les documents ne peuvent pas être récupérés. L’obsolescence des systèmes peut être remédiée par la migration des documents électroniques à un nouveau système.27

Les organismes doivent avoir une politique de conversion et de migration. De plus, cette politique doit être documentée dans votre manuel de GD et inclure les procédures adoptées pour assurer la protection et la préservation de la structure, du contenu, de l’identité et des métadonnées de conservation des documents. Cette protection et cette préservation doivent s’étendre à tous les dossiers électroniques, y compris les courriels, leurs pièces jointes, les liens, les preuves de livraison, les listes de distribution et les liens avec d’autres documents de l’organisme.

Toutefois, avant que toute activité de conversion ou de migration ne commence, la norme stipule que l’organisme doit identifier les éléments suivants:

- les fonctionnalités requises de l’ancien format;

- les fonctionnalités qui doivent être maintenues dans le nouveau format et le nouveau système; et,

- documenter toutes les décisions.

Surtout, la migration et la conversion doivent toutes deux être intégrées dans un processus d’affaires documenté, faisant partie du fonctionnement habituel du système électronique.28

Formats de conservation

La section 6.4.6.5.2 de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017 suggère aux organismes d’identifier les formats privilégiés pour la conservation des documents par type de documents. C’est-à-dire, quel type de document sera conservé et dans quel format. Les décisions concernant les formats de conservation doivent être fondées sur l’amplitude du changement qui peut être effectué avant que le document ne devienne trop dégradé pour servir de copie fiable au cours d’une procédure judiciaire. De plus, les décisions concernant le format de conservation doivent être documentées dans le manuel de GD. L’annexe C, sur la conservation, fournit des informations précieuses sur les formats de conservation.29

Assurance qualité

Les versions de 2005 et de 2017 exigent toutes deux que les organismes intègrent des mesures et des processus d’assurance qualité dans leurs programmes de GD.

L’assurance qualité signifie que le niveau de service approprié est défini et que le personnel connaît et comprend ce niveau de service. De plus, il faut que le personnel ait reçu la formation nécessaire pour offrir le niveau de service défini.

La mise en œuvre des processus d’assurance qualité est à la charge de l’archiviste et doit inclure l’évaluation du rendement, la surveillance de la conformité, les autoévaluations, les audits externes, le traitement des incidents et la documentation et certification du respect de toutes les obligations de GD. Les problèmes importants doivent être signalés à la haute direction, afin d’effectuer des modifications au programme de GD, si nécessaire.30

Éléments informatiques

Compte tenu de la tendance actuelle à la numérisation, les organismes adoptent des technologies plus rapidement que leur permet leur capacité à incorporer des protocoles appropriés dans leurs systèmes, planification technologique et gestion. Cela conduit à un chaos d’information et à des risques de non-conformité accrus, surtout lorsque les documents s’accumulent et se distribuent dans les différents systèmes, espaces, services, dispositifs et formats, et sous la garde des employés. Forbes et d’autres spécialistes du secteur estiment actuellement que l’information électronique double chaque année.31 Entre temps, sur le volume total de documents (papier et électronique), de nombreux utilisateurs des systèmes de GD estiment qu’approximativement 5-10% nécessiteront une conservation permanente. Ils conviennent, d’après l’expérience de Sharon Byrch, qu’approximativement 60% à 80% de l’information électronique d’un organisme consiste en des documents indésirables documents transitoires avec une valeur à court terme seulement, non durable tels que duplicatas, copies à titre informatif, versions obsolètes et travaux incomplets ou abandonnés; ou des documents qui sont expirés et ne sont plus nécessaires. Ces documents pourraient être légalement détruits, et de façon routinière, s’ils étaient facilement identifiables parmi les documents de l’entreprise qui sont encore nécessaires.

Les professionnels de l’informatique savent que le fouillis d’informations est coûteux. Les besoins en stockage de données et les coûts associés ne cessent d’augmenter à mesure que les entreprises continuent d’étendre leur empreinte numérique. De plus, trier l’information pertinente dans le fouillis est coûteux, en temps et en argent, pour les TI et la GD, et a un impact sur les employés; l’encombrement fait qu’il est difficile pour les employés d’identifier les documents transitoires parmi les documents officiels des entreprises lorsqu’ils recherchent des informations fiables et qui font autorité pour faire leur travail. C’est une situation désavantageuse pour toutes les parties concernées, et un facteur de motivation pour le changement et la mise en œuvre de la norme CAN/CGSB-72.34-2017, afin d’avoir une meilleure gestion des dossiers électroniques, une conformité accrue à la loi et une réduction des risques.

Au même moment où les entreprises se tournent vers le numérique pour gérer leur entreprise, les documents sur papier (analogiques) deviennent de plus en plus des documents d’archives. Par exemple, Sharon Byrch a constaté que, dans un organisme pour laquelle elle travaillait, il y avait un ratio d’environ 1:1000 de documents papier à numériques, ce qui signifie que pour chaque document papier créé, l’organisme a créé 1000 enregistrements électroniques. Ce ratio est une progression naturelle, en raison du déclin de la création de documents papier, et est courant dans plusieurs organismes.