Sagesse: 2019 Edition Volume IV

Winter 2019 Sagesse Publication

- 2019 Introduction to Sagesse.

- Ethical Concerns in the Provision of eHealth Services. By Meagan Collins, Nicole Doro, Ben Robinson, & Ariel Stables-Kennedy. Recipients of $1,000 in the 2018 ARMA Canada Essay Contest.

- IT & Modern Public Service: How to Avoid IT Project Failure and Promote Success. By Scarlett Kelly. Recipient of $600 in the 2018 ARMA Canada Essay Contest.

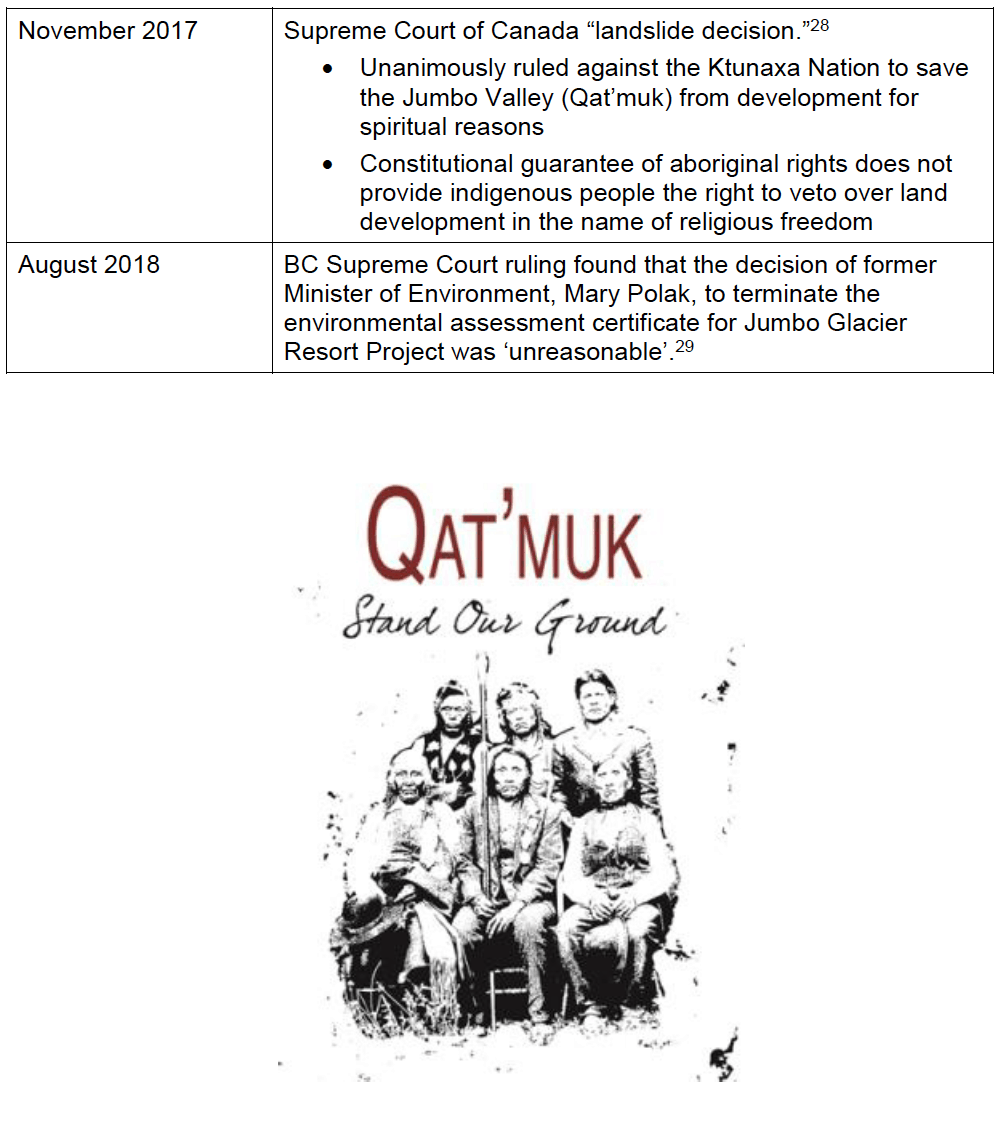

- Defending Traditional Rights in the Digital Age: Ktunaxa Nation Case Study. by Michelle Barroca, BA, MAS.

- Politique relative aux messages électroniques et son adoption. Par Barb Bellamy, CRM et Anne Rathbone, CRM.

- Email Policy and Adoption. by Barb Bellamy, CRM & Anne Rathbone, CRM.

- Thank you to John Bolton! by Alexandra Bradley, CRM, FAI

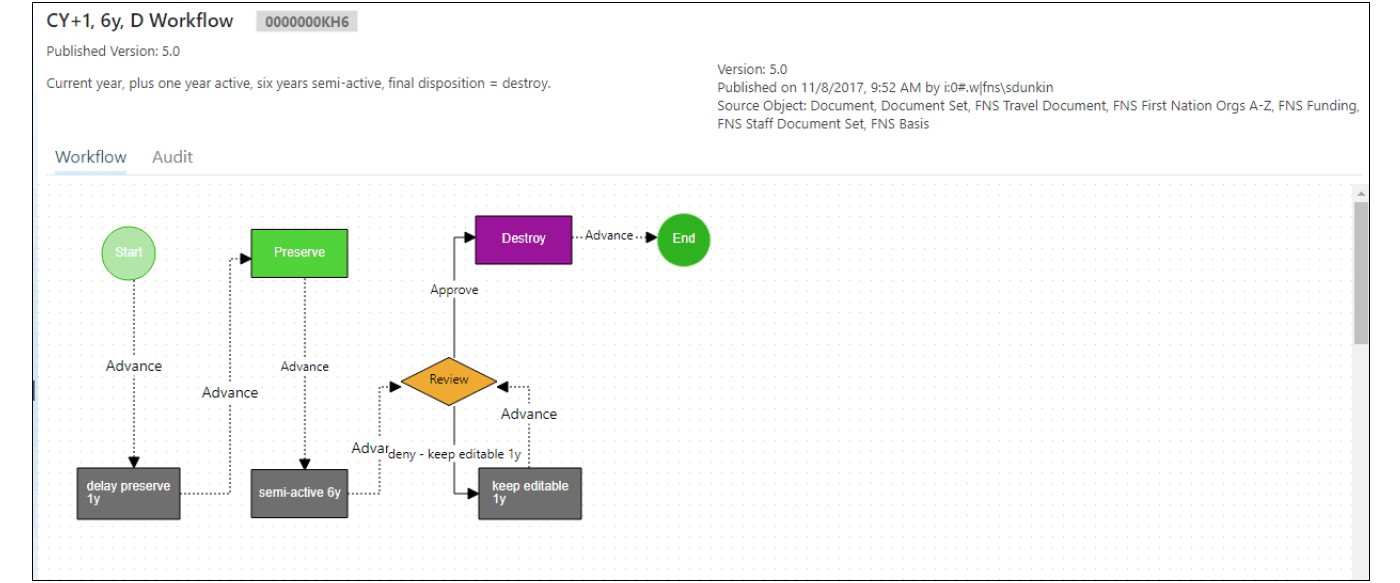

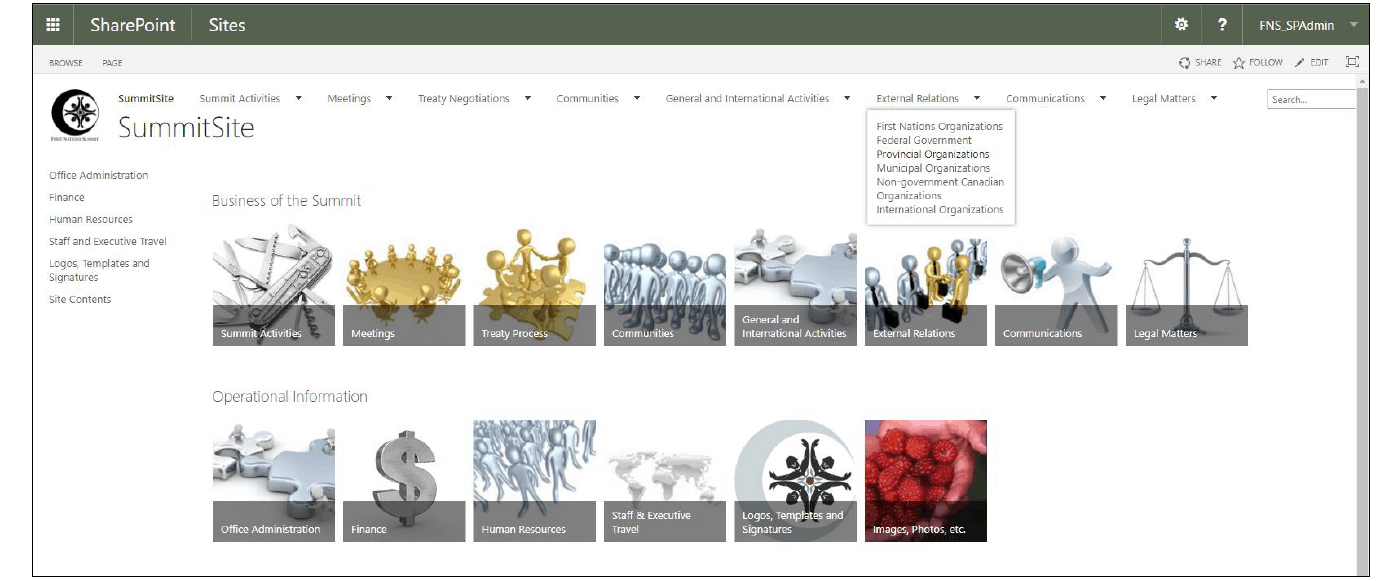

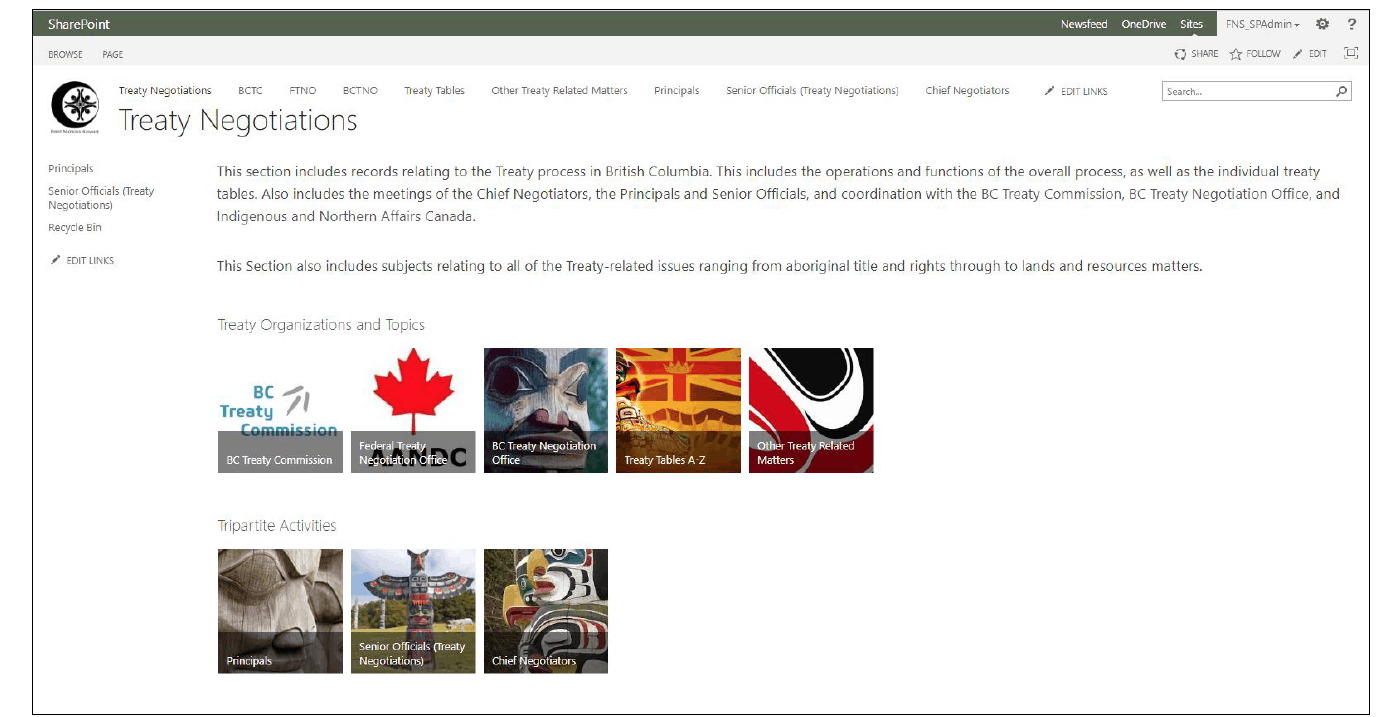

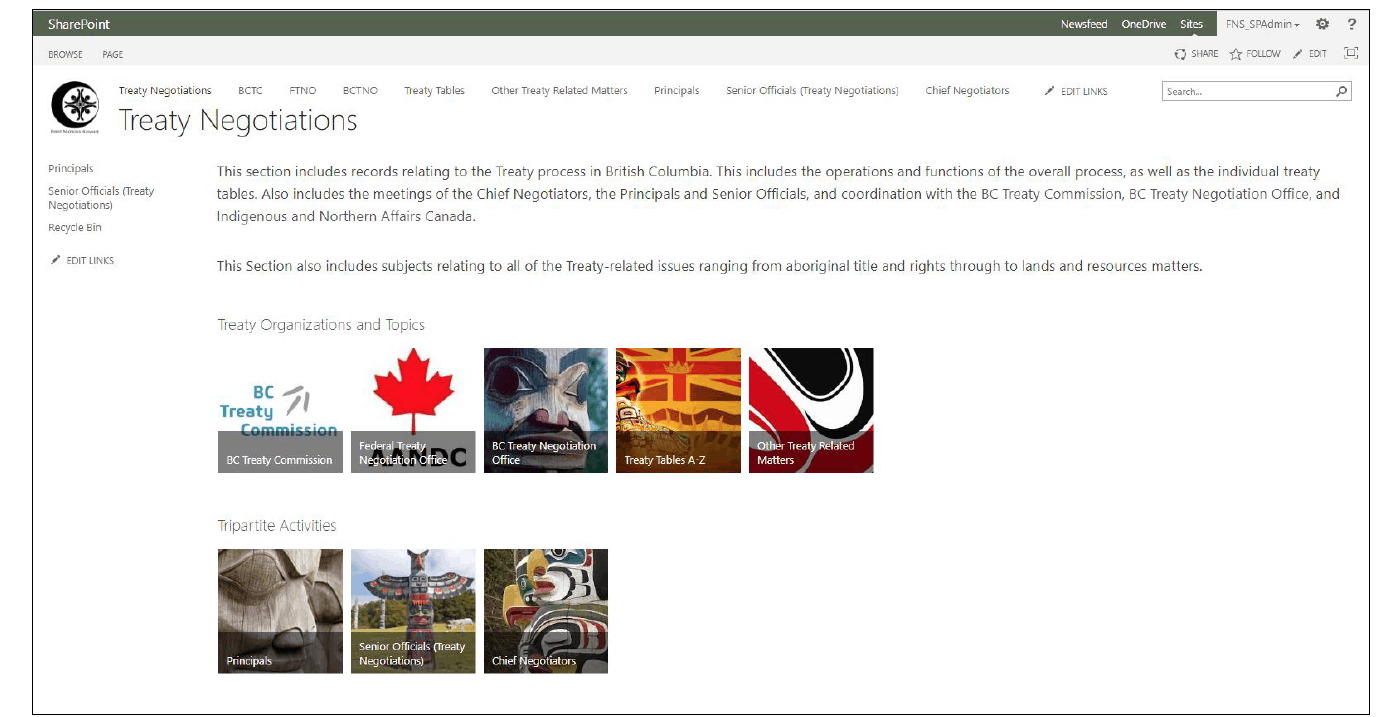

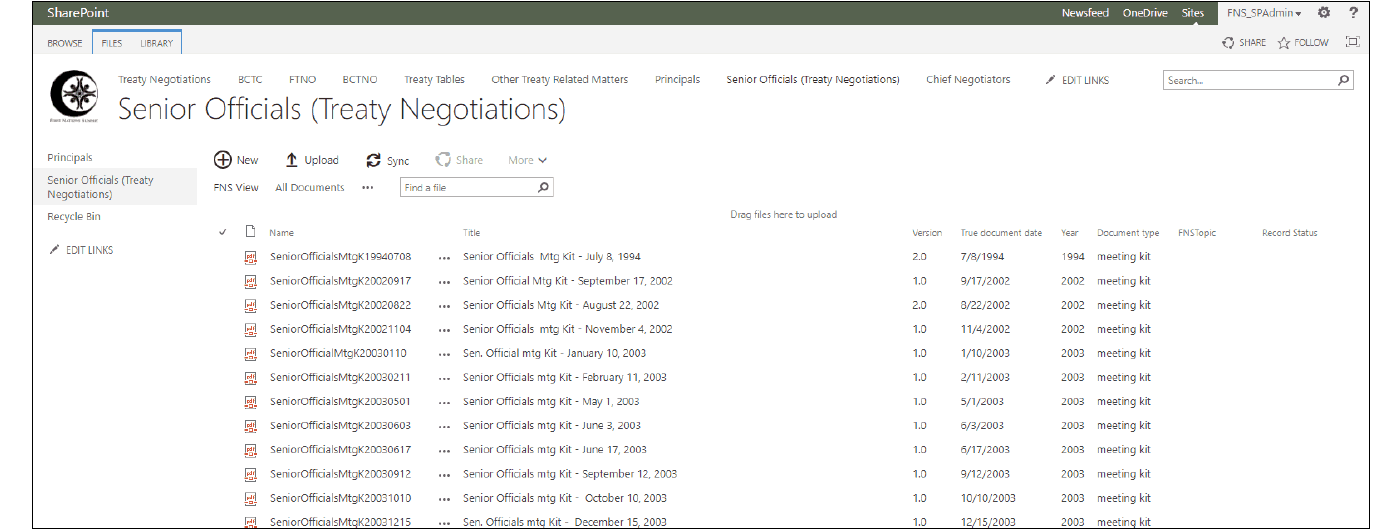

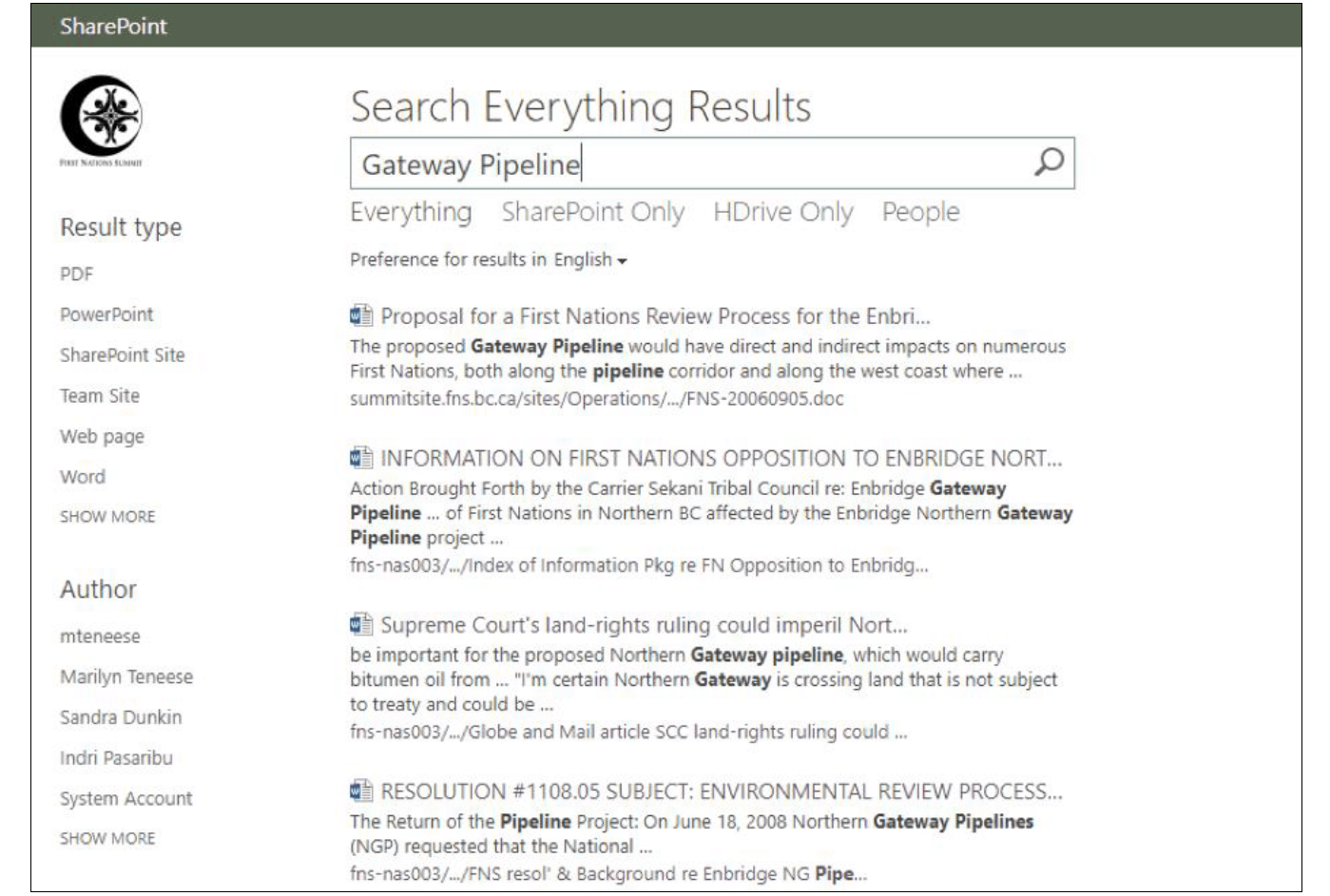

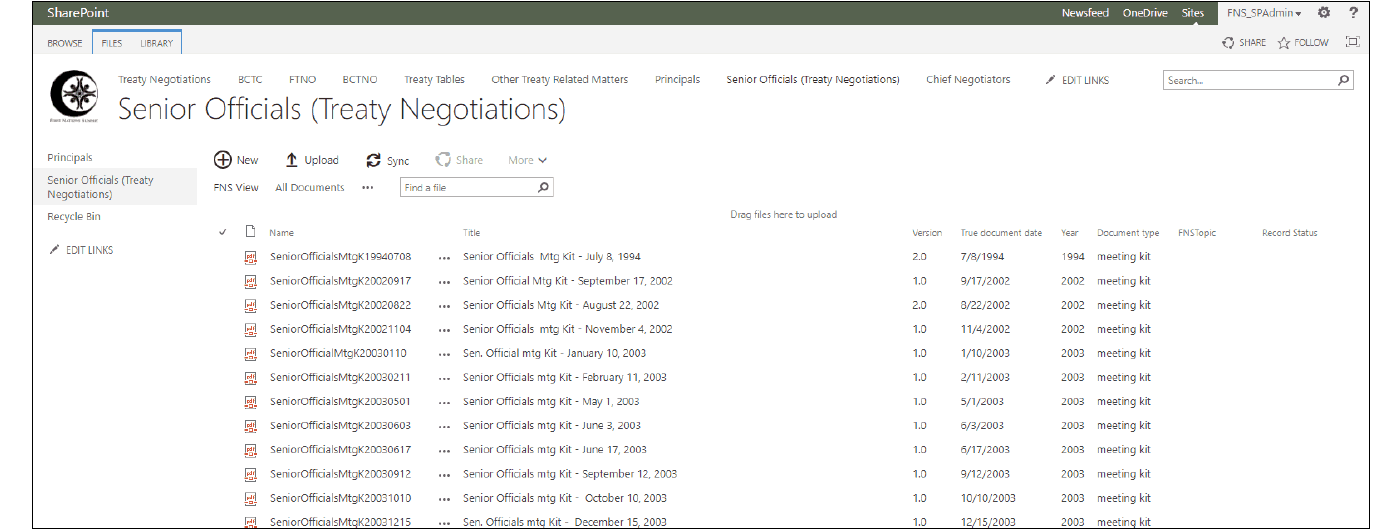

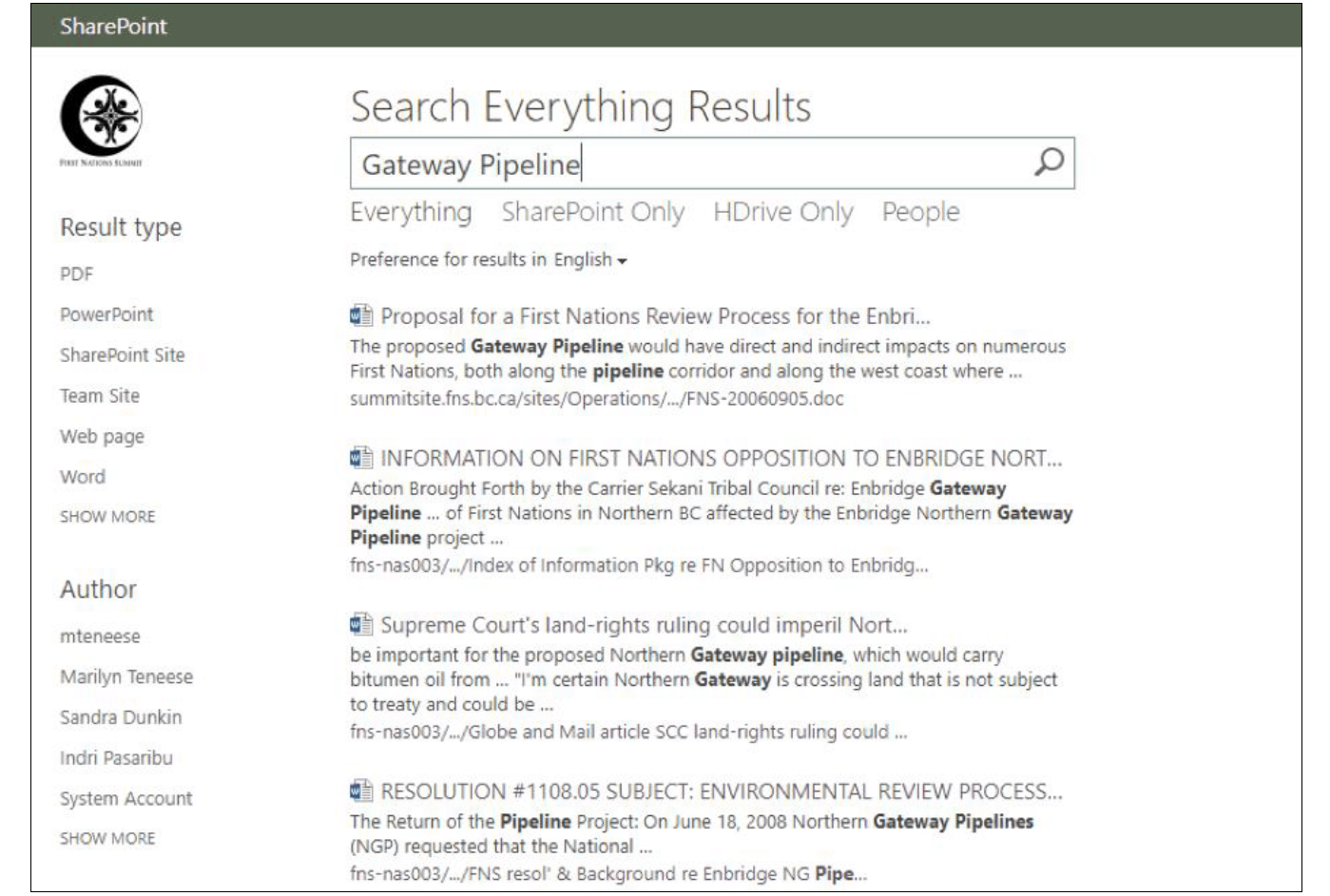

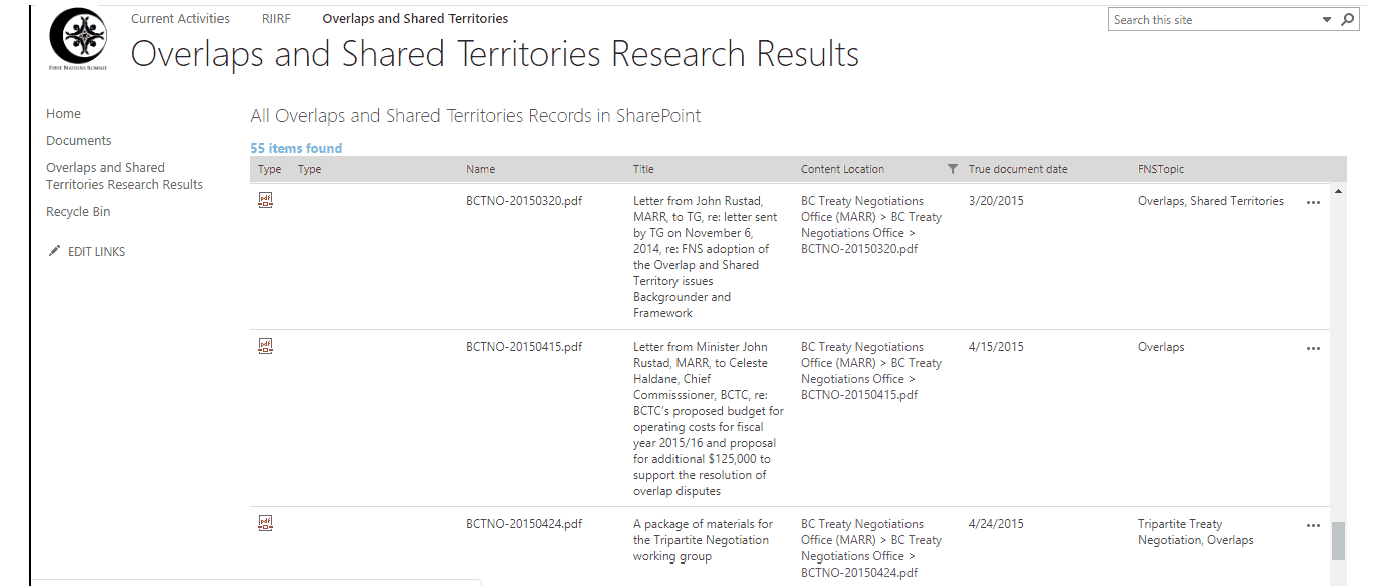

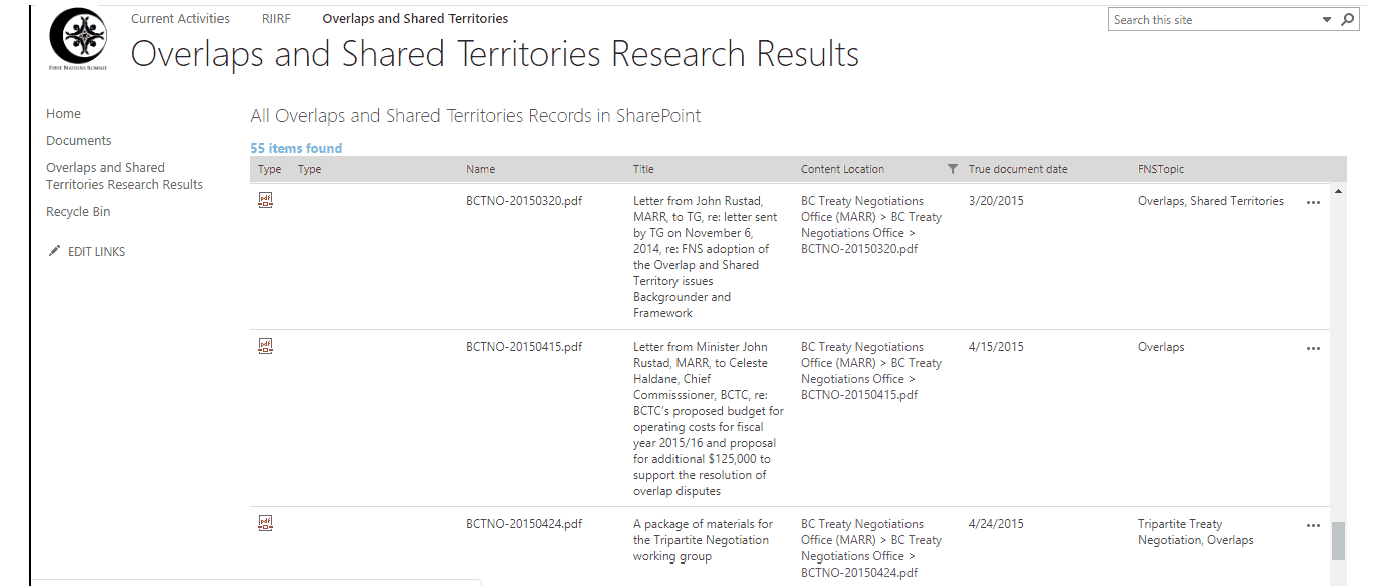

- Are we There Yet? Introduction to the SharePoint & Collabware Implementation at the First Nations Summit. by Sandra Dunkin, CRM, IGP & Sam Hoff

- Quand est-ce qu’on arrive? Introduction à l’implémentation de SharePoint & Collabware au First Nations Summit Society. Par Sandra Dunkin, CRM, IGP & Sam Hoff

- A Record of Service: The First Canadian Conference on Records Management “A Giant Success.” by Sue Rock, CRM

Biographies

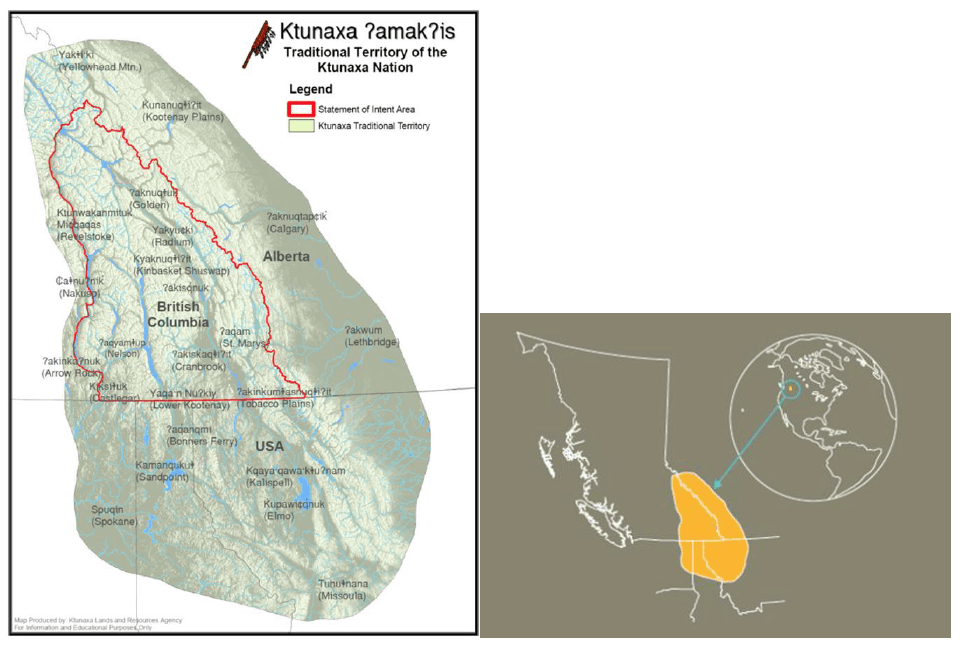

Michelle Barroca (BA, MAS) is an independent recorded information management consultant from the Kootenay region of BC. Michelle graduated from UBC’s School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies with a Master of Archival Studies degree in 2000. Shortly after university, she was hired as the City of Burnaby’s first records manager and archivist, and later worked at the City of Kelowna as the Records and Information Coordinator. For nearly a decade, Michelle has operated FY Information Management Consulting and provides services to various local governments and First Nations organizations, including the Ktunaxa Nation Council.

Barb Bellamy, CRM,has over 30 years of experience in Records and Information Management for the Utility and Energy industries. She currently specializes in Information Management Consulting and Acquisition and Divestment work within Suncor. Barbara is a Certified Records Manager and holds a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration.

Alexandra (Sandie) Bradley, CRM, FAI has been a records and information manager for over 40 years, and a member of ARMA for 35 years. Through her chapter, regional and international roles within ARMA, she is a mentor and teacher, researcher, writer and advocate for our profession. She is a Certified Records Manager and was made a Fellow of ARMA International (Number 47) in 2012. She is a member of the Vancouver Chapter, is currently a member of the Sagesse Editorial Board and also the Content Editorial Board for ARMA International.

Megan Collins holds her MA and Honours BA from Brock University in Political Science and is presently a MLIS student at Western University. She is currently completing a co-op posting working as an information management officer with the Federal Government. Her research interests include information policy, knowledge management, Big Data, privacy and surveillance.

Nicole Doro holds her MA and Honours BA in English and Critical Theory from McMaster University, and is presently a MLIS student at Western University. She is currently completing an Instructional and Research co-op at McMaster University. Her research interests include open access, institutional repositories, as well as privacy and surveillance.

Sandra Dunkin (MLIS, CRM, IGP) is the Records & Information Management Coordinator at the First Nations Summit (FNS) where she also has responsibility for IT. She is the project manager for the SharePoint implementation at the FNS and is also currently the out-going Chair of the Information Governance Advisory Committee for the First Nations Public Service Secretariat.

Sam Hoff is a Senior Consultant at Gravity Union. He is passionate about providing user experience focused solutions to meet document and records management needs. Having backgrounds in both the technical and human sides of technology and business, he has been focused on Enterprise Content Management and Records Management solutions based on SharePoint for the past seven years.

Scarlett Kelly holds both Master of Public Administration (MPA) and Master of Library and Information Studies (MLIS). Her research focuses on IT project management, strategic planning, information/data policy, and change management. Currently a Research Specialist at Canada Revenue Agency, Scarlett is gaining valuable experience in legal and business research.

Anne Rathbone has 22 years experience in the public sector establishing, implementing and maintaining records and information management programs. She earned her Certified Records Manager (CRM) designation in 2010. Currently, Anne is the Records Management Coordinator for the Sunshine Coast Regional District.

Ben Robinson is a poet, musician and librarian. In October 2017, Bird, Buried Press published his first poetry chapbook “Mayami.” In 2018 he was named the Emerging Artist in the Writing category at the Hamilton Arts Awards. He is currently preparing an article for publication on policing and security in the public library.

Sue Rock, CRM is a records management consultant with a diverse workload including records management assessments, records audits, classification systems and retention schedules. She ghost writes policies, procedures, memos, letters, debates, rebuttals, opinions, guidelines, action checklists and presentations. Sue’s educational background comprises a Bachelor of Arts, Université d’Ottawa, and a Professional Specialization Certificate in International Intellectual Property Law co-sponsored by both the University of Victoria, Canada and St. Peter’s College Oxford, England. She is a Past President, ARMA

Calgary Chapter, and a Chapter Member of the Year award winner. Her publications include “A Record of Service: Bob Morin, CRM” ARMA Canada Sagesse, “RIM’s Role in the Technology Lifecycle”, ARMA International, “Managing Privacy Conflicts Across Borders – Vendor Awareness and Action”, Security Shredding & Storage News, and team lead for ARMA International Guideline “Records Management for Information Technology Professionals.” Sue is owner of The Rockfiles Inc. and an operating partner of Trepanier Rock ™, with specific focus on ensuring records management principles are embedded

into information management technology solutions.

Ariel Stables-Kennedy holds a BSc in Kinesiology from the University of Waterloo and is currently completing her MLIS at Western University in London, Ontario. Her research interests include instructional design, the information literacy learning needs of STEM students, and information ethics.

Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management an ARMA Canada Publication Winter, 2019 Volume IV, Issue I

Introduction

Welcome to ARMA Canada’s fourth issue of Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management, an ARMA Canada publication.

Sagesse Editorial Team

The Sagesse Editorial Board would like to take this opportunity to gratefully acknowledge and thank John Bolton who was a founding member of Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management. John resigned mid 2018 after making many invaluable contributions to this publication. His impact on Sagesse and the RIM and IG community are significant. Sandie Bradley has captured some of his brilliance in an article titled “Thank you to John Bolton!” in this issue.

The Editorial Board would like to welcome Sandra Dunkin, MLIS, CRM, IGP to the editorial team. Sandra brings a wealth of ARMA and workplace experience, from her work on the ARMA Vancouver Chapter, the ARMA Canada team as Program Director, to her work at First Nations Summit. Sandra has already demonstrated her commitment and dedication to the Sagesse team performance. She also has an article in this edition – see “Are We There Yet?”

2018 University Contest

There’s a new addition to Sagesse’s 2019 edition and we are excited to share that in 2018, ARMA Canada and the Sagesse Editorial Board held an essay contest for graduate students enrolled in graduate information management programs in a number of Canadian universities. The article that best met the theme, Canadian Issues for Information Management, received $1,000 while the runner up received $600.

We are honoured to announce that the team of: Meagan Collins, Nicole Doro, Ben Robinson and Ariel Stables-Kennedy from the University of Western Ontario were the $1,000 recipients with their article “Privacy and Ethical Concerns in the Provision of eHealth Services.” Their article explores an ethical analysis of data collection policies of Canadian live eHealth service providers and comments to what extent they conform to the Canadian Medical Association’s Code of Ethics.

Scarlett Kelly, from Dalhousie University, was the $600 recipient with her article “Information Technology and Modern Public Service: How to Avoid IT Project Failure and Promote Success.” Scarlett looks at a global scan that indicates that IT projects may have as high as an 85% failure rate discussing it from the point of view of the people involved, IT processes and the product to deliver to users.

Congratulations to our students!

To our readers, prepare to be captivated with the content, writing and research in these articles as well as the others in this edition.

2019 Sagesse Articles

Continuing with Sagesse’s tradition of providing thought provoking content, this 2019 issue features the following articles:

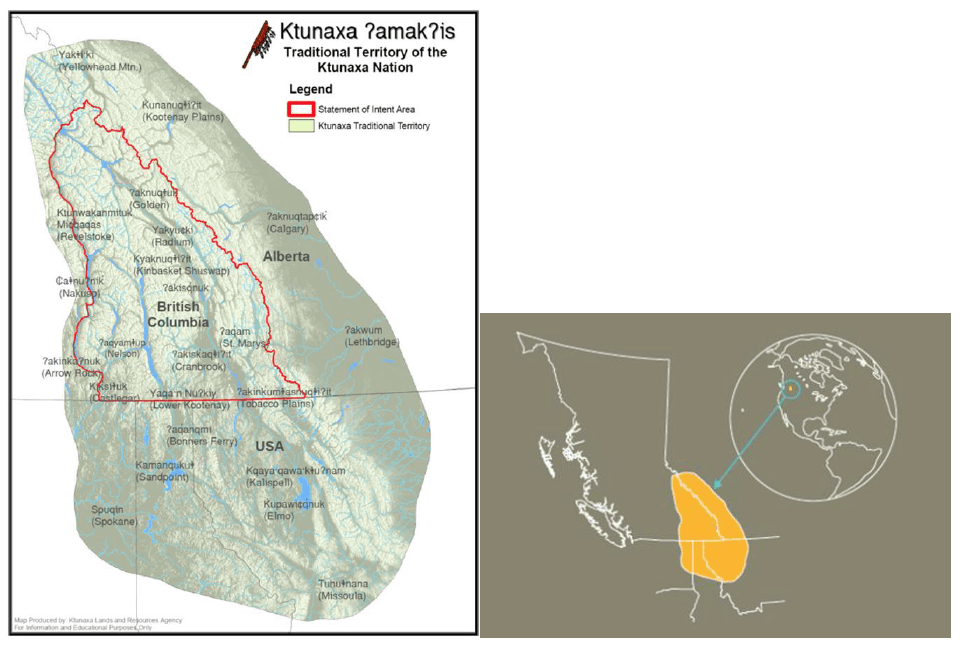

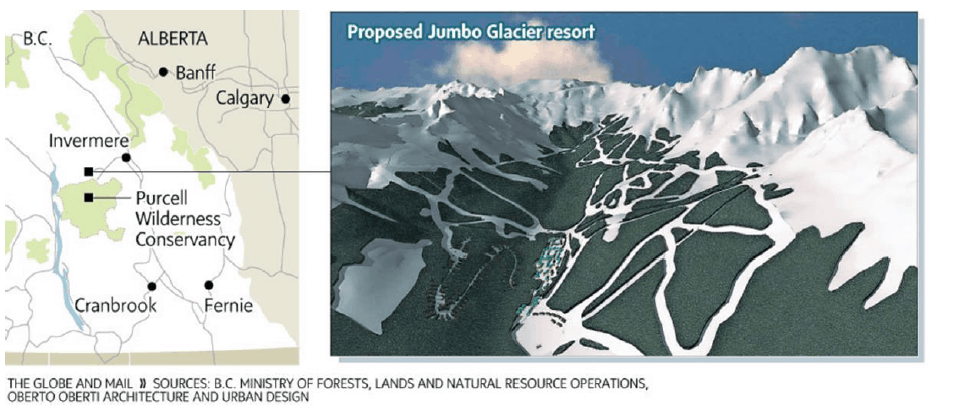

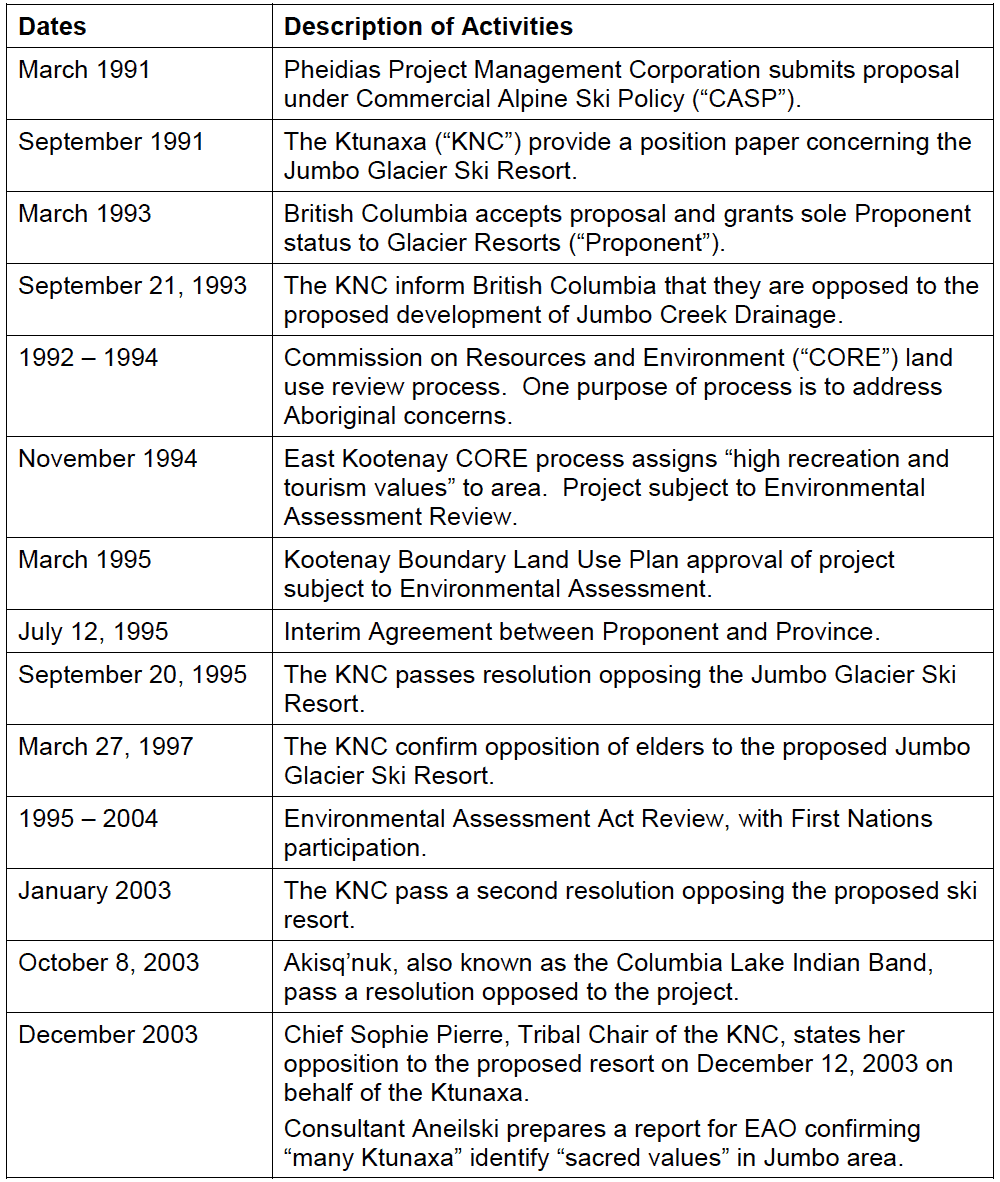

- Michelle Barroca, BA, MAS, provides a case study in her article “Defending Traditional Rights in the Digital Age: Ktunaxa Nation Case Study,” of Ktunaxa Nation’s experience with using business and cultural records to legally defend traditional rights in opposing permanent development in a culturally significant and ecologically sensitive area in British Columbia’s southeast quadrant.

- Barb Bellamy, CRM and Anne Rathbone, CRM, discuss the challenges an organization faces in establishing an email policy and the compliance issues the employees need to embrace in “Email Policy and Adoption.” They provide an excellent array of tools to assist this process by using catch phrases, branding and gamification. This paper has been translated into French.

- Alexandra (Sandie) Bradley, CRM, FAI, features an article that pays tribute to and provides the biography of John Bolton, CRM. John was a founding member of Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management, and his wisdom was a guiding light while a member of this team. In “Thank you to John Bolton,” she describes his RIM journey and the many accomplishments he achieved in his

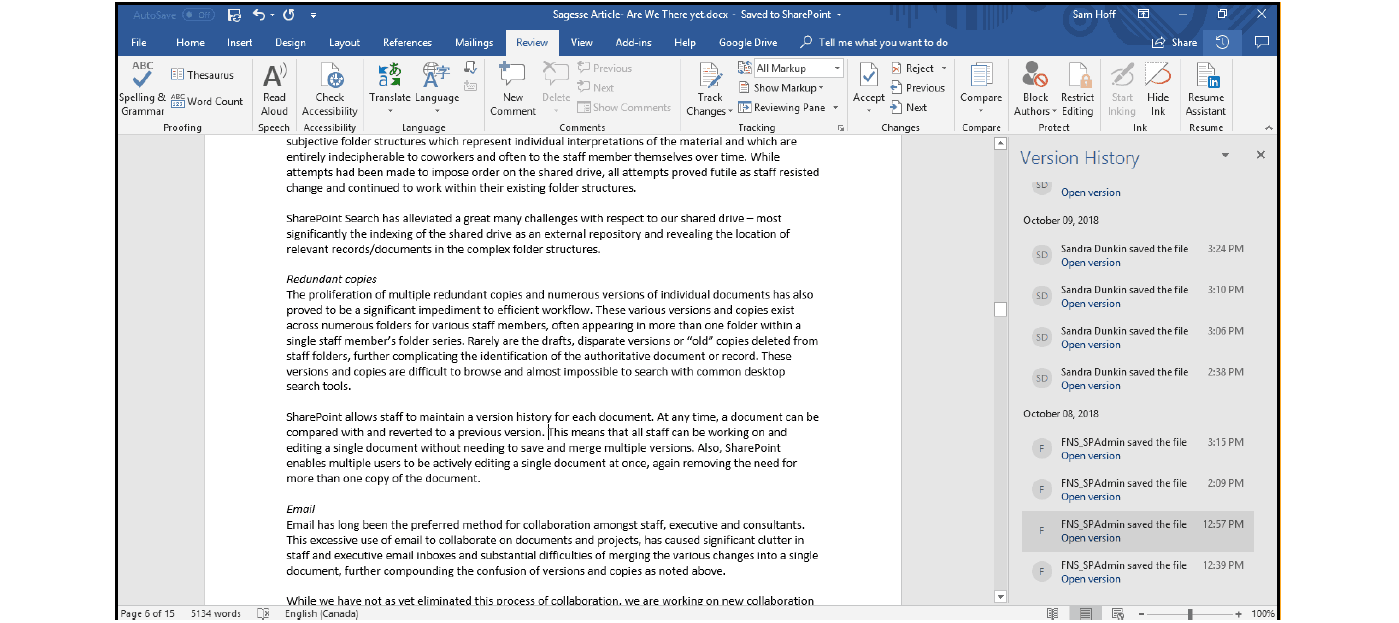

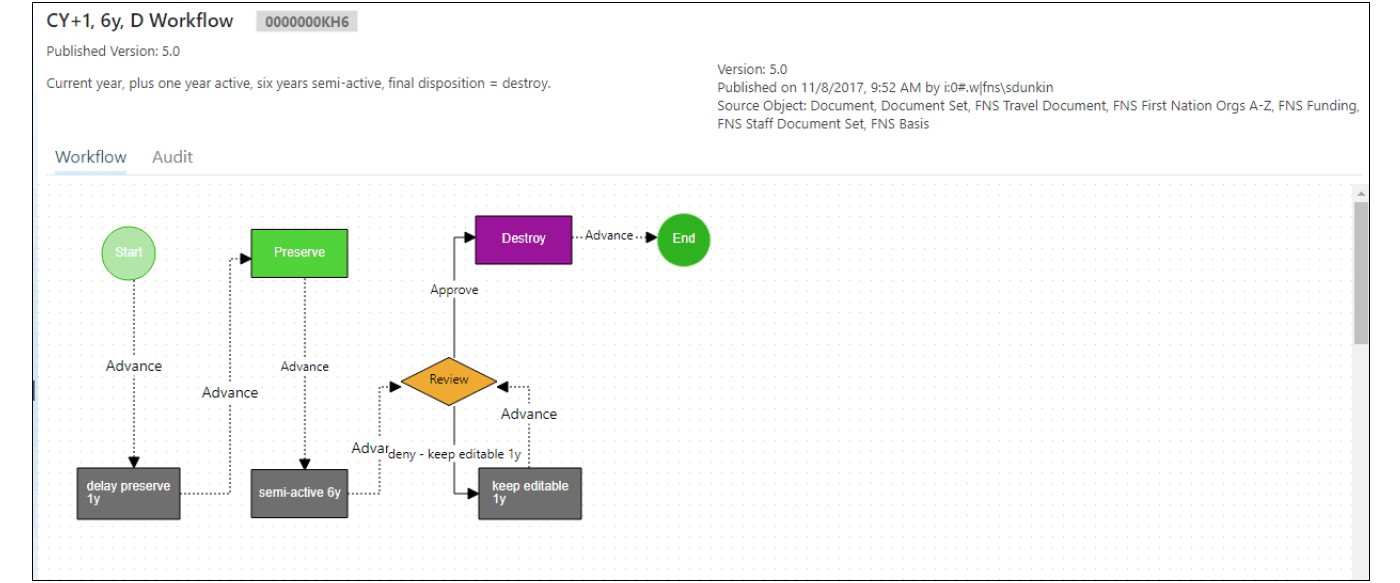

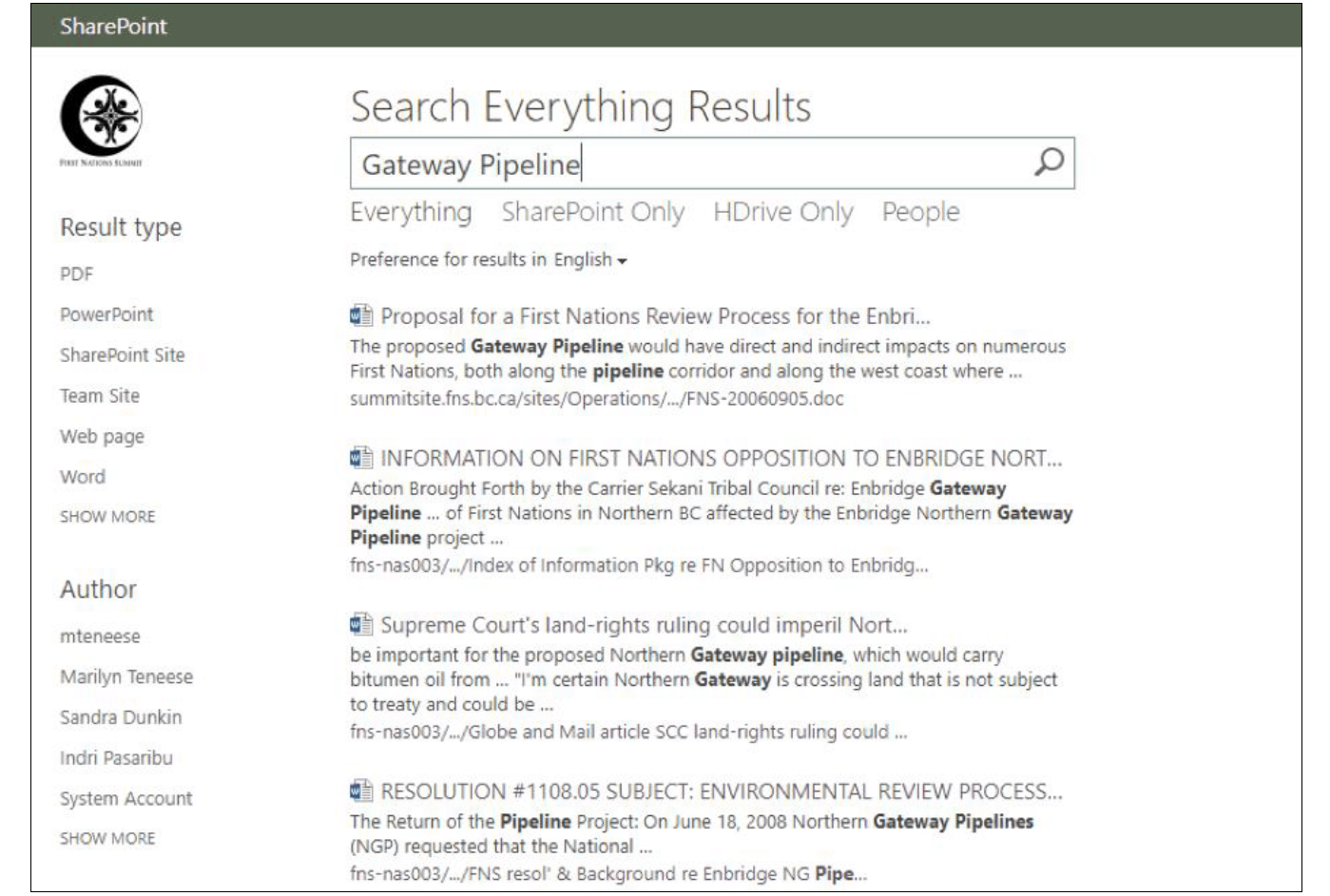

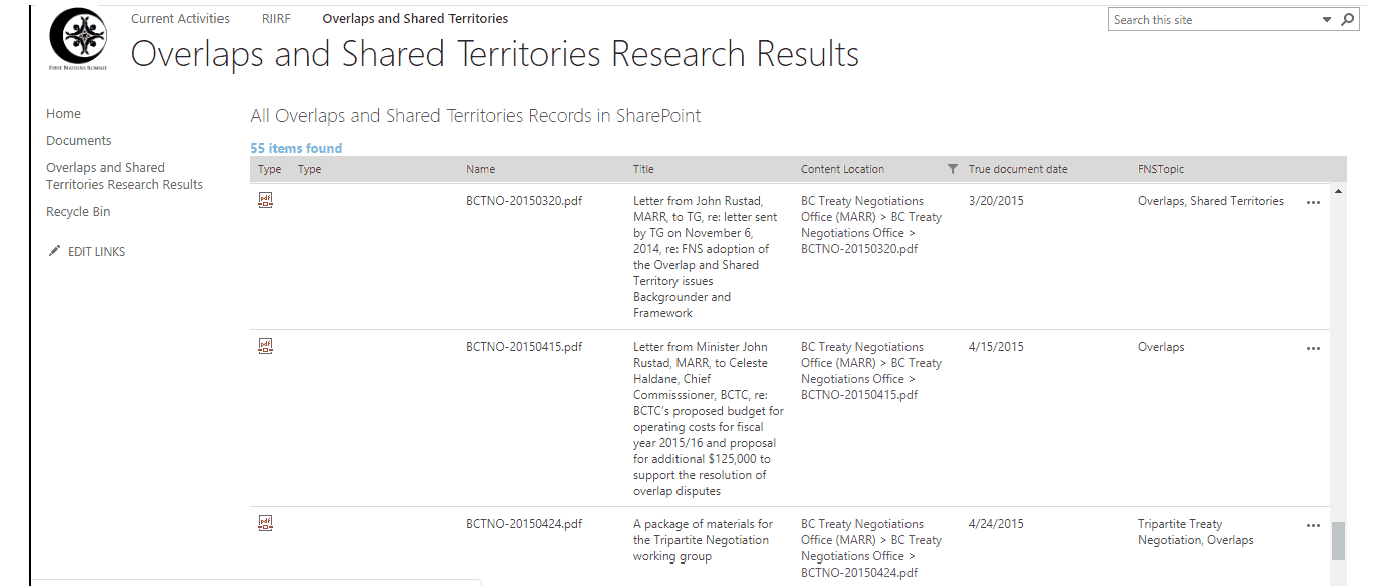

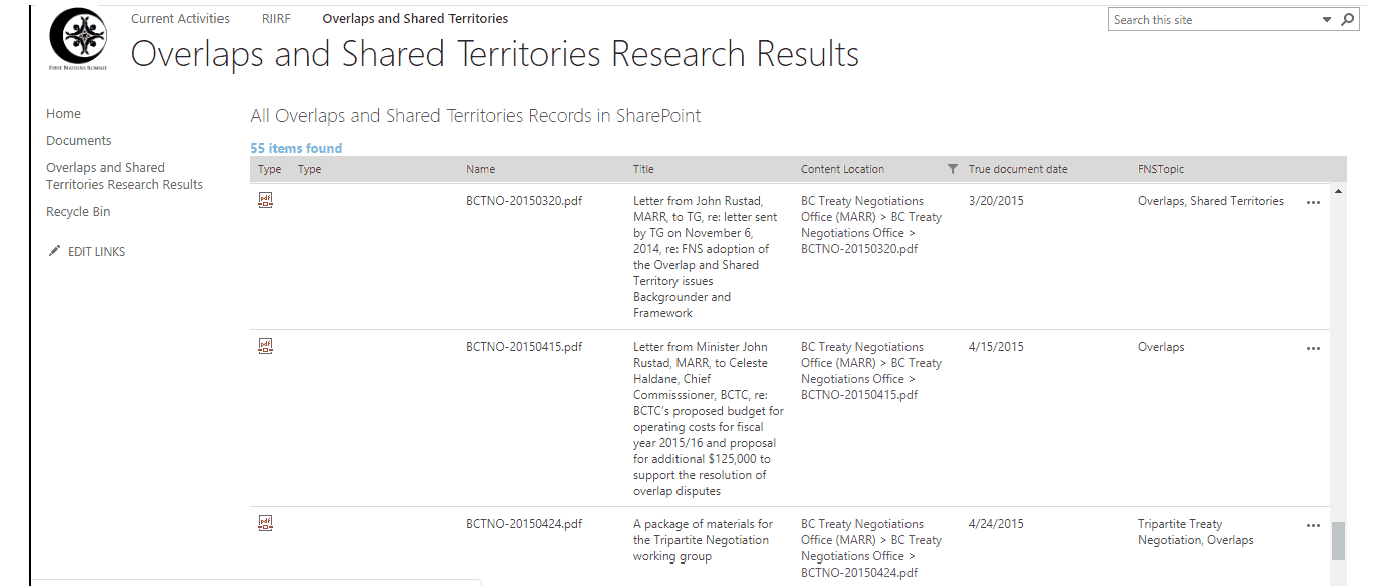

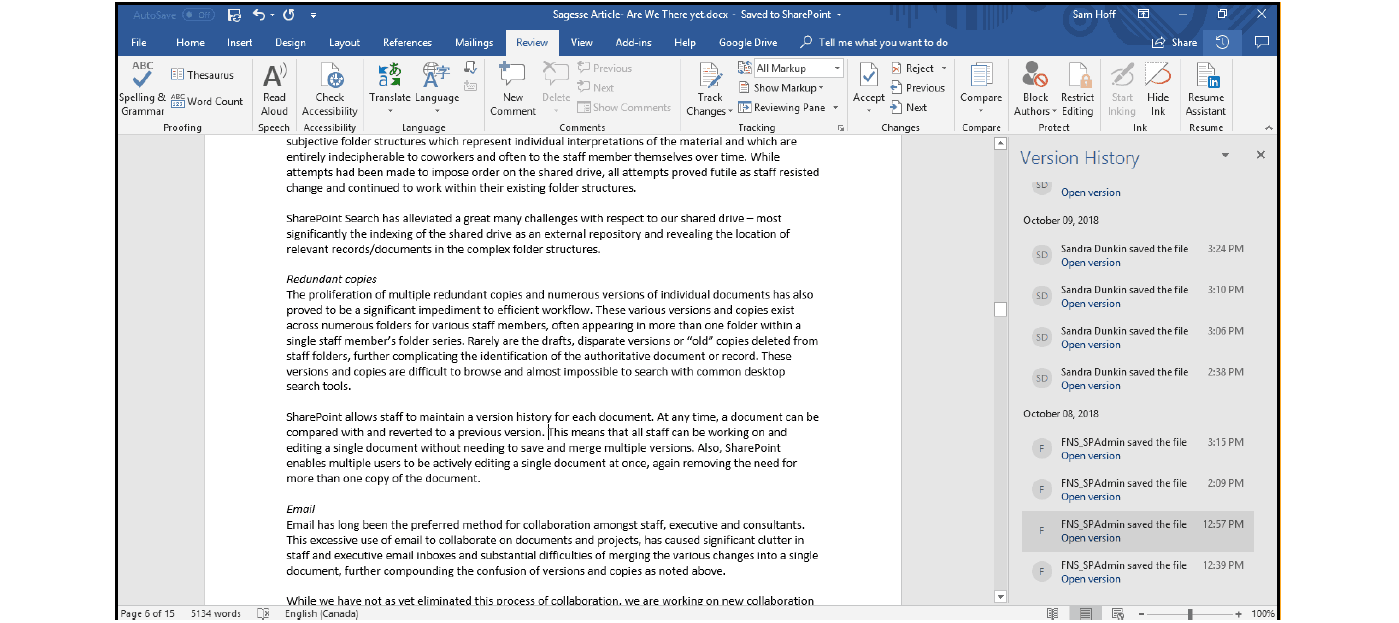

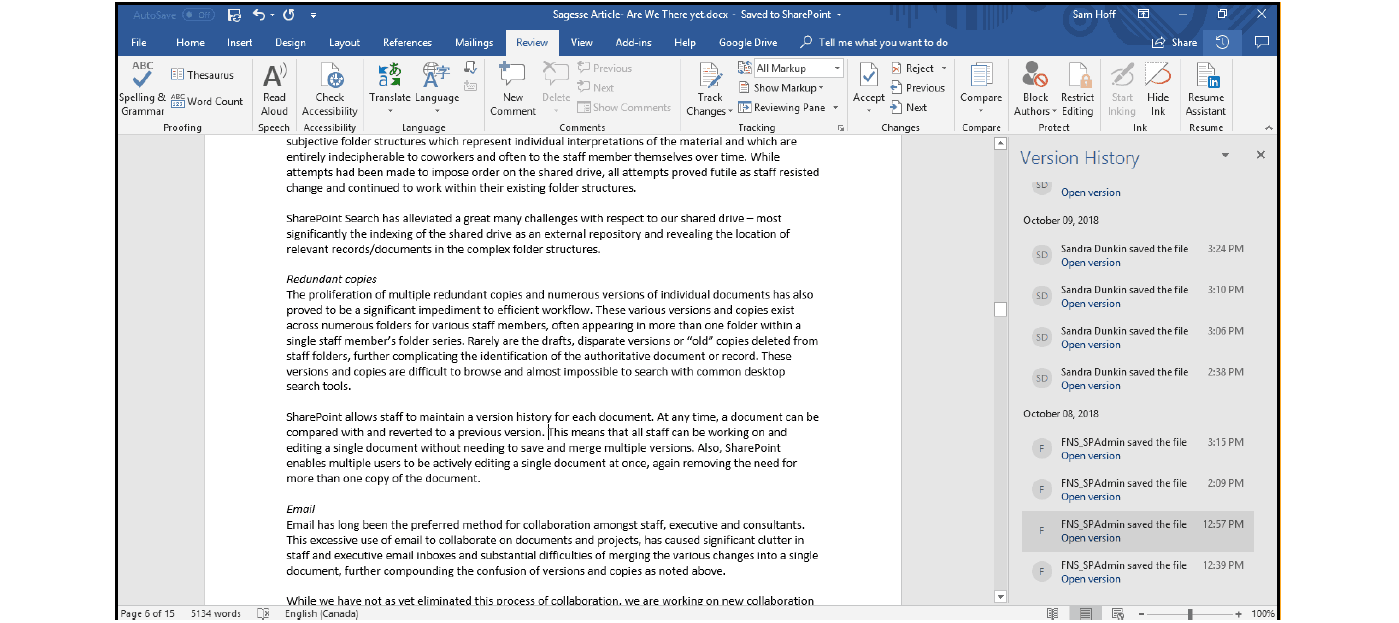

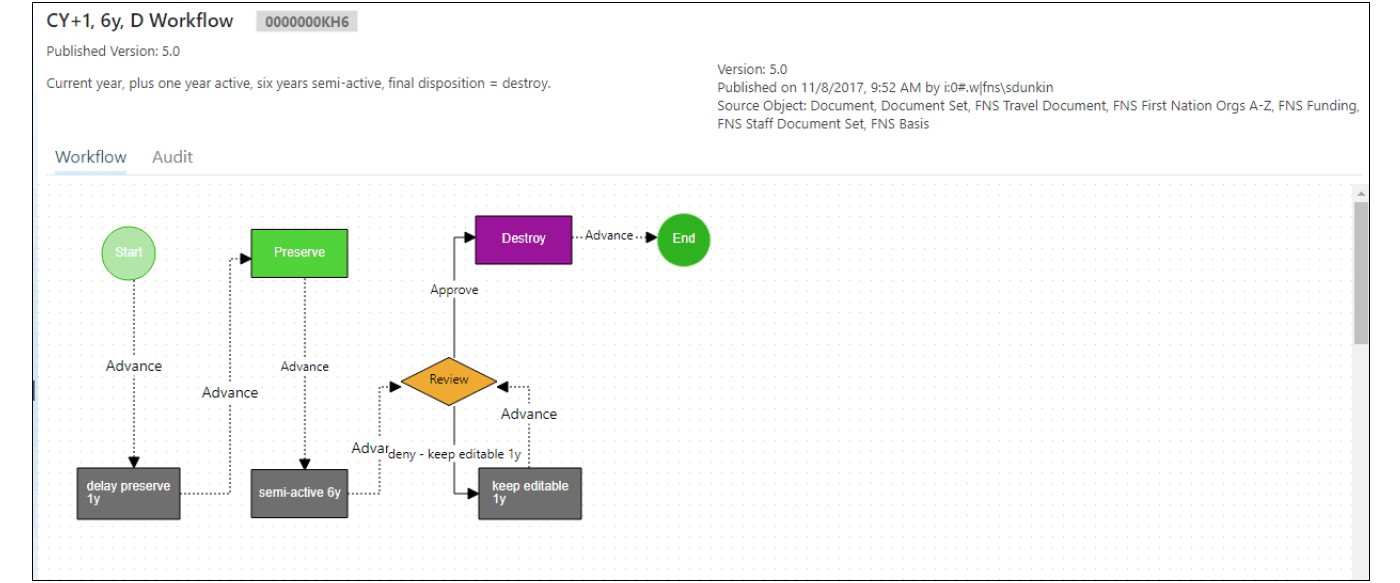

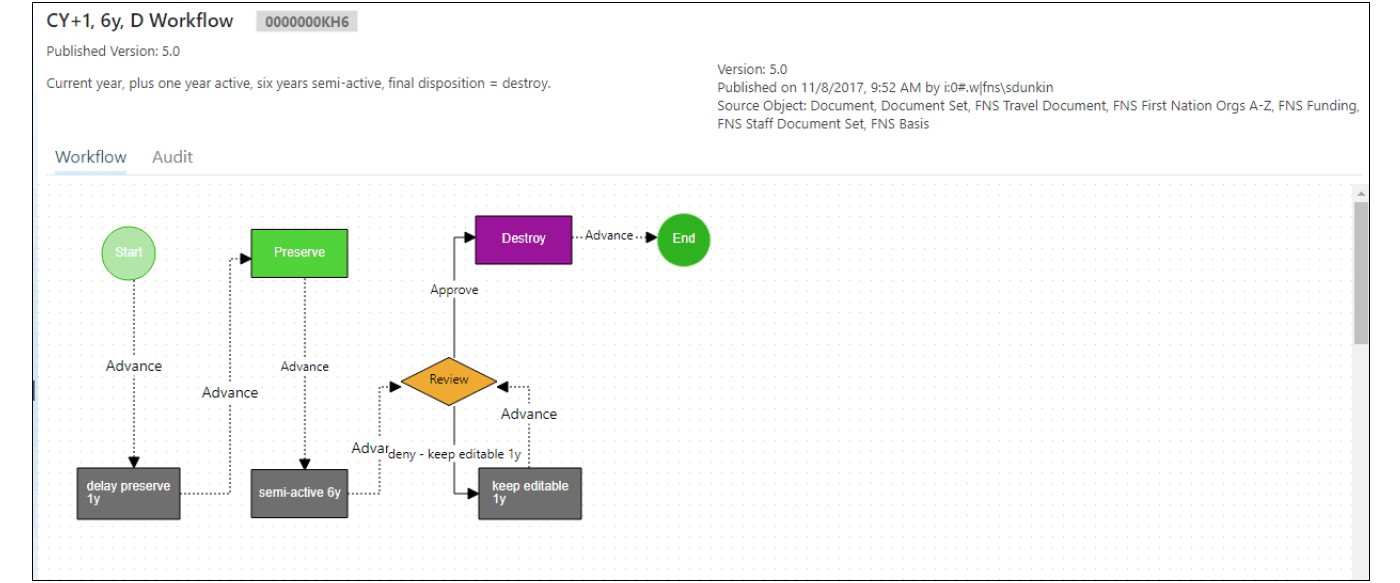

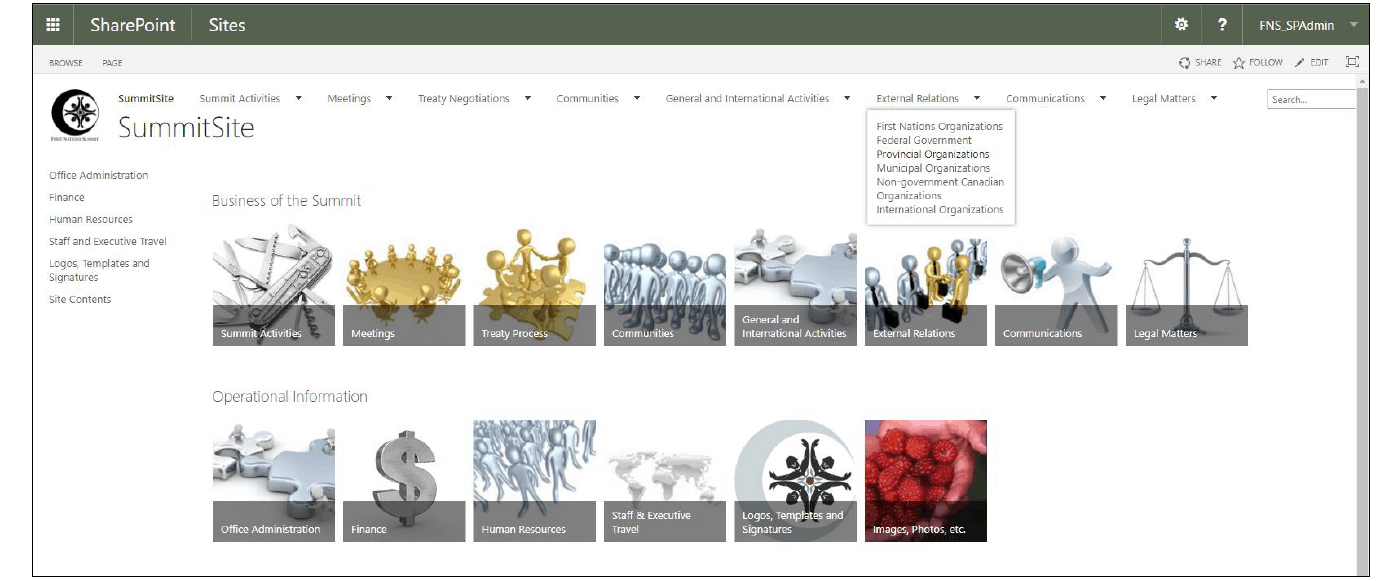

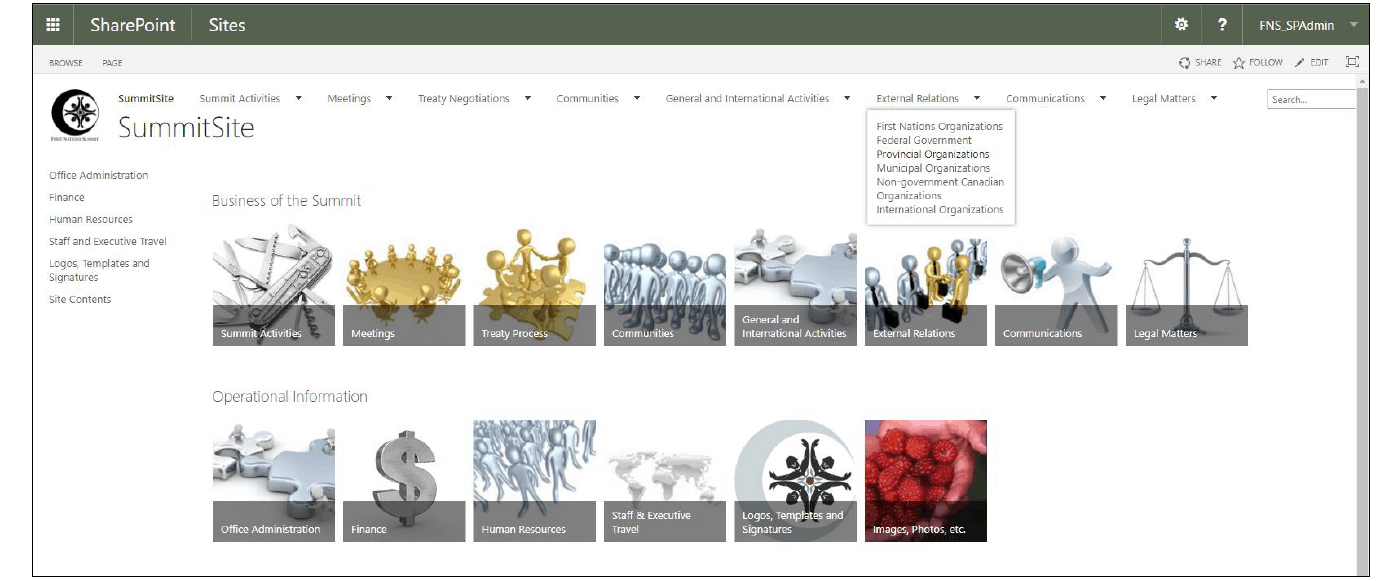

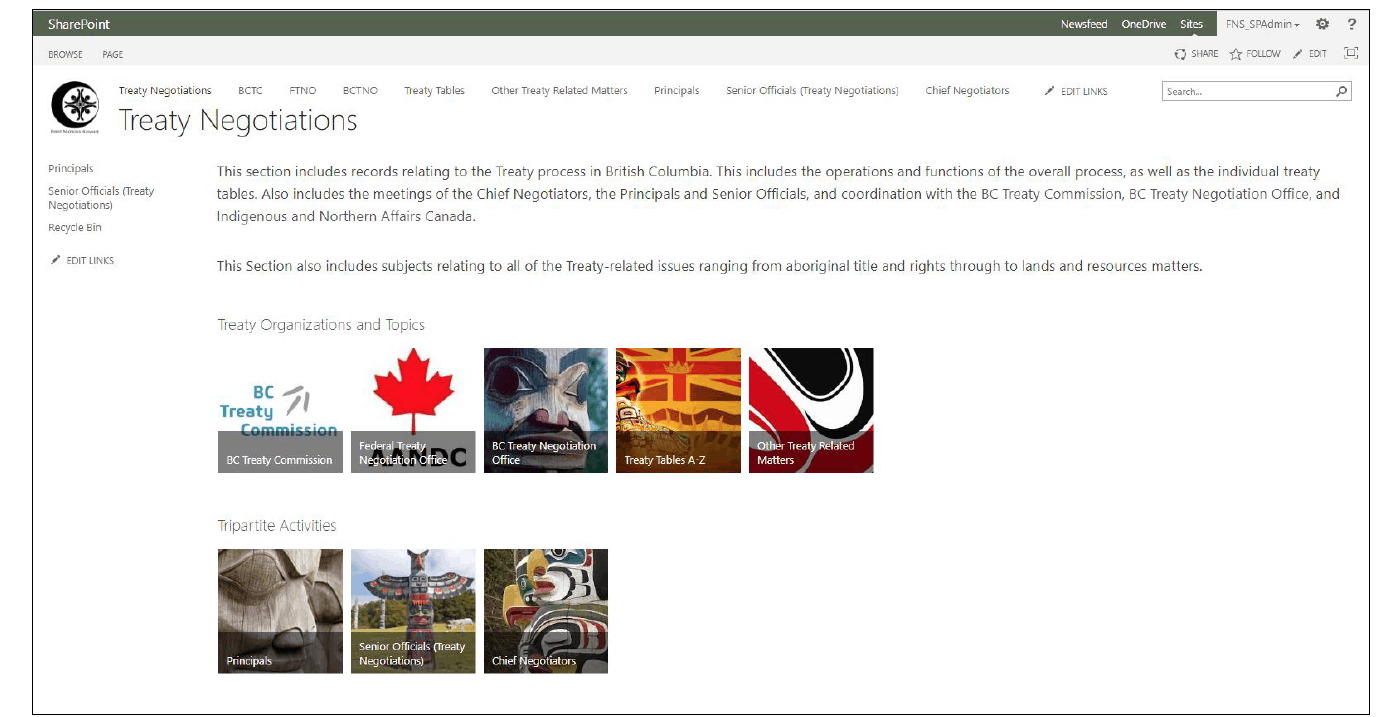

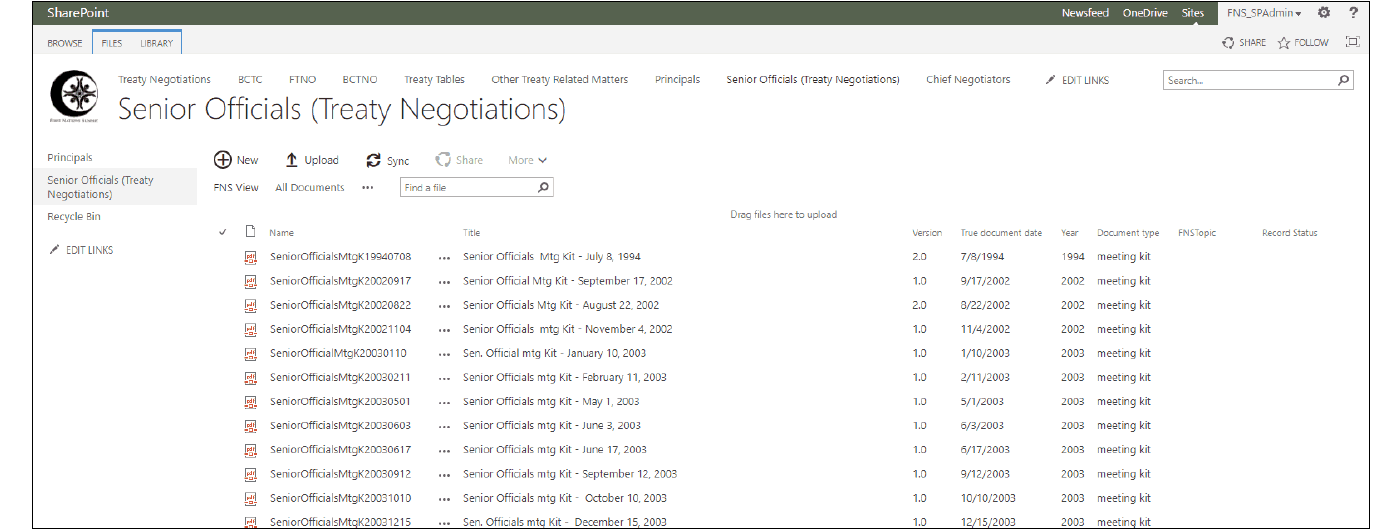

- “Are We There Yet?” an article by Sandra Dunkin, MLIS, CRM, IGP and Sam Hoff, ECM Consultant, explores a SharePoint implementation project conducted at the First Nations Summit while underscoring the lessons learned, missteps, failures and eventual successes. Also addressed are the challenges of change management, user training and adoption and various upgrades as users engage with SharePoint. This paper has also been translated into

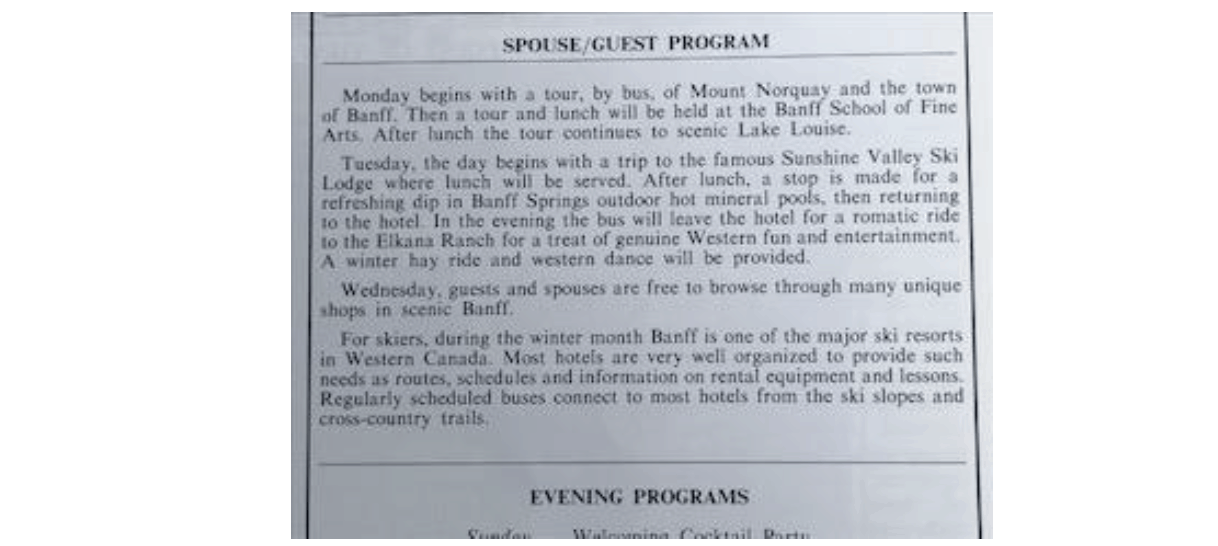

- Who doesn’t enjoy an ARMA Canada Conference? Sue Rock’s, CRM, article “A Record of Service: The First Canadian Conference on Records Management “A Giant Success,” looks back at the very first ARMA Canada conference, held in beautiful Banff, Alberta in February 1980. Discover how some of ARMA Canada traditions were developed and have evolved over the years.

Please note the disclaimer at the end of this Introduction stating the opinions expressed by the authors in this publication are not the opinions of ARMA Canada or the editorial committee. We are interested in hearing whether you agree or not with this content or have other thoughts or recommendations about the publication. Please share and forward to: sagesse@armacanada.org

If you are interested in providing an article for Sagesse or wish to obtain more information on writing for Sagesse, visit the ARMA Canada’s website – www.armacanada.org – see Sagesse.

Enjoy!

ARMA Canada’s Sagesse’s Editorial Review Committee:

Christine Ardern, CRM, FAI, IGP; Alexandra (Sandie) Bradley, CRM, FAI; Sandra Dunkin, MLIS, CRM, IGP; Stuart Rennie, JD, MLIS, BA (Hons.); Uta Fox, CRM, FAI, Director of Canadian Content.

Disclaimer

The contents of material published on the ARMA Canada website are for general information purposes only and are not intended to provide legal advice or opinion of any kind. The contents of this publication should not be relied upon. The contents of this publication should not be seen as a substitute for obtaining competent legal counsel or advice or other professional advice. If legal advice or counsel or other professional advice is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.

While ARMA Canada has made reasonable efforts to ensure that the contents of this publication are accurate, ARMA Canada does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, currency or completeness of the contents of this publication. Opinions of authors of material published on the ARMA Canada website are not an endorsement by ARMA Canada or ARMA International and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of ARMA Canada or ARMA International.

ARMA Canada expressly disclaims all representations, warranties, conditions and endorsements. In no event shall ARMA Canada, its directors, agents, consultants or employees be liable for any loss, damages or costs whatsoever, including (without limiting the generality of the foregoing) any direct, indirect, punitive, special, exemplary or consequential damages arising from, or in connection to, any use of any of the contents of this publication.

Material published on the ARMA Canada website may contain links to other websites. These links to other websites are not under the control of ARMA Canada and are merely provided solely for the convenience of users. ARMA Canada assumes no responsibility or guarantee for the accuracy or legality of material published on these other websites. ARMA Canada does not endorse these other websites or the material published there.

Privacy and Ethical Concerns in the Provision of eHealth Services

by Meagan Collins, Nicole Doro, Ben Robinson, and Ariel Stables-Kennedy

Introduction

The development of the internet and the advancement of digital technologies have resulted in life-saving access to information, especially within the medical industry. Whereas, before the introduction of these technologies, individuals would need to visit a doctor’s office for their health-related questions, they can now consult resources themselves on the internet. A study showed that 83% of internet users around the world have searched for health information1. In 2012, the number of Canadians who regularly used the internet to search for medical and health- related information at home was over 65%, making it the sixth most common use of the internet in Canada2. Along with increased access to medical information, Information Communication Technology (ICT) is also an integral tool in the field of health services known throughout Canada as eHealth.

eHealth is defined as blending the internet, telecommunications, and information technology with medical services provision3. According to the Government of Canada, the incorporation of eHealth into the mainstream medical treatment framework has been a significant priority for Canada over the past 20 years4. Since 2010, Canada has budgeted $20 billion towards the creation of a national health infostructure allowing for advances in several aspects of healthcare service models5. Integrated technologies now allow patients to receive medical care through telemedicine applications, a major benefit for those who live in rural areas or who are homebound. It also provides a more convenient service model by allowing patients affected by rare medical disorders to receive service from distant specialists6. The recognized benefits of this system have resulted in 53% of Canadian primary-care physicians using some form of electric medical reporting technologies, up from 14% in 20007. While the improvements to medical services were widely accepted as significantly beneficial, eHealth adoption also allowed for many potential advances in Health Informatics (HI).

HI “involves the application of information technology to facilitate the creation and use of health-related data, information and knowledge8.” As well, HI serves two functions in the eHealth model. First, it is designed to improve the experience of clinical practitioners through information and knowledge management. Second, it has also helped to improve the accessibility of health information for caregivers, patients and the public9. This emphasis on HI and the resulting data collection within these medical services has led to an increase in concerns surrounding the ethics of data collection in this particularly sensitive field10.

This study aims to add to the international discussion by performing an ethical analysis of the data collection policies of Canadian live eHealth service providers and to what extent they conform to the Canadian Medical Association’s (CMA) Code of Ethics. In addressing this question, this paper will begin with a brief overview of related work in the field of data privacy pertaining to medical information to situate this study within the overall discourse on the topic.

Next, the reasoning for using the CMA’s Code of Ethics as an ethical framework and the general methodological approach will be further explained. After exploring the results of the examination of the Privacy Policies and Terms of Use agreements of several eHealth service providers, the discussion will focus on the efficacy of current policy provisions and potential future research areas within this topic.

Literature review

Research analyzing the ethics of the eHealth industry began to emerge in the early 2000s.

The early literature was primarily theoretical, mostly addressing the possible implications of eHealth services and technologies as an emerging trend within the field. The progression of work in this area has grown to include more practical analyses, in addition to the theoretical studies on eHealth, as concerns about privacy, data collection, equality and quality of medical care have become more prominent. Prior studies that address data collection can be organized into four main categories. This paper will provide some background on the literature that focused on:

- the importance of protecting privacy and confidentiality in eHealth services as an ethical imperative for the industry;

- the need to have ethical standards and frameworks in place to regulate the collection and use of data in eHealth services;

- how the industry defines “health data” and how this impacts ethical data collection and use, and

- the integration of eHealth data and social media

Ethical Imperative of Privacy and Consent

Early research looked at the integration of ICT in the health field and discussed the potential implications of these technologies for patient privacy and confidentiality. Dyer framed the need for privacy as a tenet of the ethical code of the American Medical Association and discussed the emergence of eHealth technology as a threat to the patient-physician bond, which shifted to a physician-customer model11. Following this concern, other scholars focused on the need for privacy in order to ensure patients trust and understand the health system that their physicians operate within in order to feel safe providing sensitive but accurate information12 13 14 15. Chaet et al. addressed a further complication of this issue in their discussion of the potential breach of patient privacy through the use of third-party platforms stating, “websites that offer health information may not actually be as anonymous as visitors think; they may leak information to third parties through code on a website or implanted on patients’ computers16.”

Research on this topic has often been split between a focus on the need for collected information to be de-identified for the purposes of protecting individual anonymity while also emphasizing the need for flexibility in data collection to allow for advanced analysis of sensitive information for the benefit of improving the service delivery of our universal healthcare system17. Other studies look at embedding privacy in the very design of these online platforms to ensure protection of patient privacy but also to manage the custody of data and consent18.

Need for Ethical Provisions and Regulation

Studies that focused specifically on the ethical imperative of privacy within the medical services field are often related to other studies that speak to the need for regulations or ethical codes to be embedded within the eHealth framework. Wadhwa and Wright specifically address the issue that the ethics of the medical industry have always been evolving, and the move towards an eHealth model is just another example of a period when society needs to update its ethical understandings of the practice for the digital age19. Soenens was among the earlier voices on this issue stating the importance of ensuring the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath remains ingrained in eHealth services20. Other literature in this area looks beyond system design to examine physicians themselves as important privacy actors. Derse and Miller argue that physicians should only use eHealth systems that are transparent about their privacy policies and meet acceptable ethical standards of patient confidentiality21.

Another branch of research looks at the role state regulators play in the eHealth system.

Studies conducted on this topic have sought to examine how state privacy regulations in the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) have been characterized as barriers to the continued success and advances of eHealth systems22. They have also addressed the lack of regulation and the power of third-party organizations to control the management of personal health data23. Additional studies have explored the ownership of patient data in third-party platforms and the effect this has on whether medical data can be used for informed improvements to the medical care system for the benefit of the overall public good, especially in countries with publicly funded healthcare like Canada24.

Defining Health Data and Securitization

Along with analyzing medical data regulation, other studies addressed the secondary issue of how to understand and define personal health data from a regulatory perspective.

Kleinpeter highlights how recent digital devices enable the constant collection of personalized health data at an unprecedented level25. This type of collection makes it difficult for legislators to determine which types of data to regulate and how to regulate them. It would be important to make the distinction between data collected during an individual patient’s diagnosis versus anonymized data for the purpose of medical research. There may even be some types of patient data that should be legally prohibited to collect altogether.

Some critics have noted that the lack of clarity regarding ownership of this data makes it especially difficult to regulate ethically. For example, Lee noted that, “Unlike victims of breaches of financial data, to whom reparations can be made, victims of breaches of private health data cannot be ‘made whole’; information cannot be ‘taken back.’26”

eHealth, Social Media, and Medical Advertising

The growth of social media platforms has become a more common theme within eHealth data discourse. As more social media components are added to eHealth services and patients are encouraged to engage, individuals are sharing their health stories and providing their medical data to commercial platforms more regularly. Even when these platforms are managed by public healthcare systems, this increased sharing of health information makes the privacy issues much more complicated. While taking a largely positive view of social media sites and eHealth services, Winkelstein also echoes some of this concern27. Other studies have specifically analyzed third-party platforms and discussed how the ethical gaps in their processes should be addressed28. The literature has also addressed situations where health data has been released with informed consent but is later provided to a third-party organization which combines that data with non-health-related data in order to be able to do targeted advertising based on a patient’s particular health conditions29.

This extensive body of work, along with the structured literature review performed by Khoja, Durrani and Nayani shows that ethical and legal issues within the field of eHealth studies are, and will likely continue to be a significant research area30. Up until now, this research has tended to focus on the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe and has been largely theoretical in nature, analyzing and critiquing the system as a whole rather than undertaking in- depth analyses of individual services. As such, this study provides a unique perspective on the ethical discourses in eHealth by focusing specifically on the data collection and terms of use practices of major eHealth services within the Canadian healthcare system.

Theoretical Framework

The CMA Code of Ethics will serve as the ethical framework for this investigation of the chosen eHealth services. Specifically, the “Privacy and Confidentiality” codes from the CMA’s Code of Ethics were used to measure each platform on a pass-fail basis. This Code of Ethics was chosen as the framework because of its geographic and political relevance, as it “constitutes a compilation of provisions that can provide a common ethical framework for Canadian physicians31.” As physicians operating within the Canadian healthcare system are required to follow this code, it will be used as a framework to evaluate the recent evolution of this service model. As the CMA Code of Ethics was last updated in 2004 and deemed “still relevant” after a review in March of 2018, this study will include recommendations for future adaptation and revision32.

Methods

Since the objective of this research is to evaluate eHealth services and their publicly available privacy policies, the researchers located the platforms through popular online search methods. All searches were performed through Google, as it is the most popular search engine among Canadians and as such, likely where users will turn for their online health information33. The search queries used to locate the eHealth platforms were “Canada online health chat,” “Canada telehealth services,” “Canada live health chat,” “virtual doctor Canada,” “online doctor Canada free,” and relevant hits that appeared within the first one to three pages were selected.

Only services that facilitated conversations (including chats or teleconferences) between trained healthcare providers, whether that was a doctor, Registered Nurse, or Registered Nurse Practitioner, were considered. Mental health helplines that featured live chats were also considered, as these platforms had similar capabilities for live chat and thus, have potential implications for the privacy of users’ personal health data. Ultimately, 18 platforms were chosen for consideration based on this search criteria: GOeVISIT, National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC), sexualhealthontario, Dialogue, Ontario Telemedicine Network (OTN), Livecare, Viva Care, Maple, Equinoxe LifeCare (EQ Care), YourDoctors.Online, Medicuro, Mental Health Helpline, youthspace.ca, Toronto Distress Centre Online Chat and Text Service (ONTX), Medeo, MDKonsult, Akira, and Ask The Doctor.

The chosen inclusion criteria allowed for both mobile applications and websites (which may license to third-party vendors) to be considered. Although technically the term “telehealth” encompasses both telephone calls as well as digital health services, telephone health services (i.e. voice calls) were excluded to narrow the scope of the project. Platforms that offered services such as video chats were included provided these services were not the sole eHealth service available on that platform. All chosen platforms had a live, online communication exchange component, whether via a pre-arranged appointment for a text conversation, a videoconference (ex. Maple) or by waiting in a queue for the next available professional (ex. youthspace.ca, Mental Health Helpline).

First, each service was examined to determine its funding model (private, public, or non- profit), if advertisements were used, if the patient was charged a fee for the service, or if the services were funded through the existing provincial healthcare system. Each service’s social media presence was also examined to determine whether they promoted their social media channels to users, required their users’ social media information or provided the option to sign-in to the service using existing social media accounts. Next, the accessibility of each platform’s privacy information was evaluated. The researchers took note of the presence (or lack thereof) of the Privacy Policy on the home page, and if the Privacy Policy or Terms of Use discussed how data were collected and used. The reading level of the Privacy Policy and the Terms of Use were also evaluated using the Flesch-Kincaid readability assessment embedded in Microsoft Word.

This reading test approximates a grade level required to understand a document, based on average sentence length and the average number of syllables per word. For example, a score of 8.0 implies that someone in 8th grade could understand the document34. Finally, each platform’s Privacy Policy was compared to each of the CMA’s “Privacy and Confidentiality” Codes to see if it was compliant35.

A potential source of error for this study is that the authors do not have authoritative documents for these organizations and services. For example, some services did not appear to have privacy documents, user agreements, or explicit methods of funding after extensive searching by the researchers, however, this does not mean that those documents do not exist; they are simply inaccessible to the public. The fact that the authors of this study who have significant training in digital literacy and researching suggests that these documents are also likely inaccessible to the general population using these services.

Results

Business Model

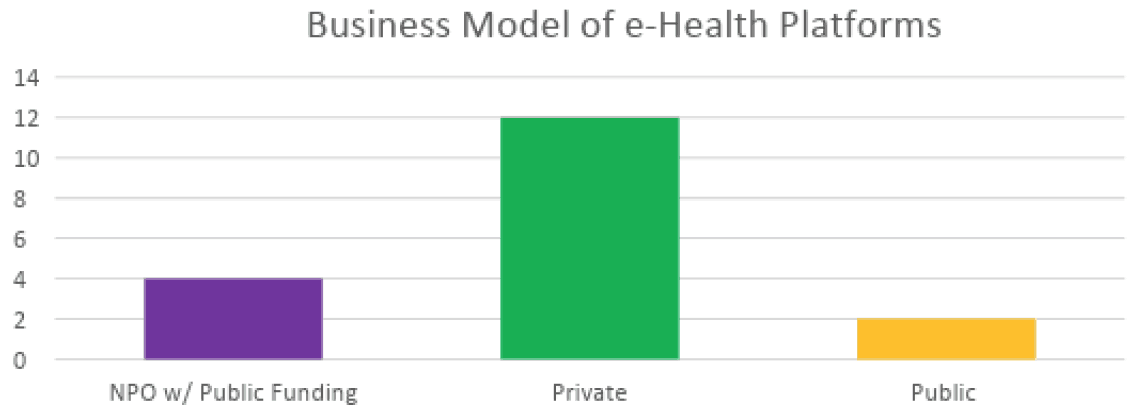

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the majority of eHealth services were privately owned and operated (12). Beyond this, the other funding models included ownership by a non-profit organization receiving government funding (4) and publicly funded services (2).

Figure 1: Business models of the surveyed eHealth services

All of the publicly funded and non-profit eHealth services examined for this study were free to Canadian users. While some private eHealth services were free, most charged a fee for access to their product. Two models emerged: a pay-per-visit model and a membership-based model. The mean cost of accessing a pay-per-visit eHealth service was $42.89 Canadian dollars (CAD) while the median cost was $45 CAD. Alternatively, subscription-based models ranged from $15 CAD to $150 CAD per-month per-member.

Only two services, Livecare and Viva Care, both privately owned and operated, utilized advertisements.

User Data Collection

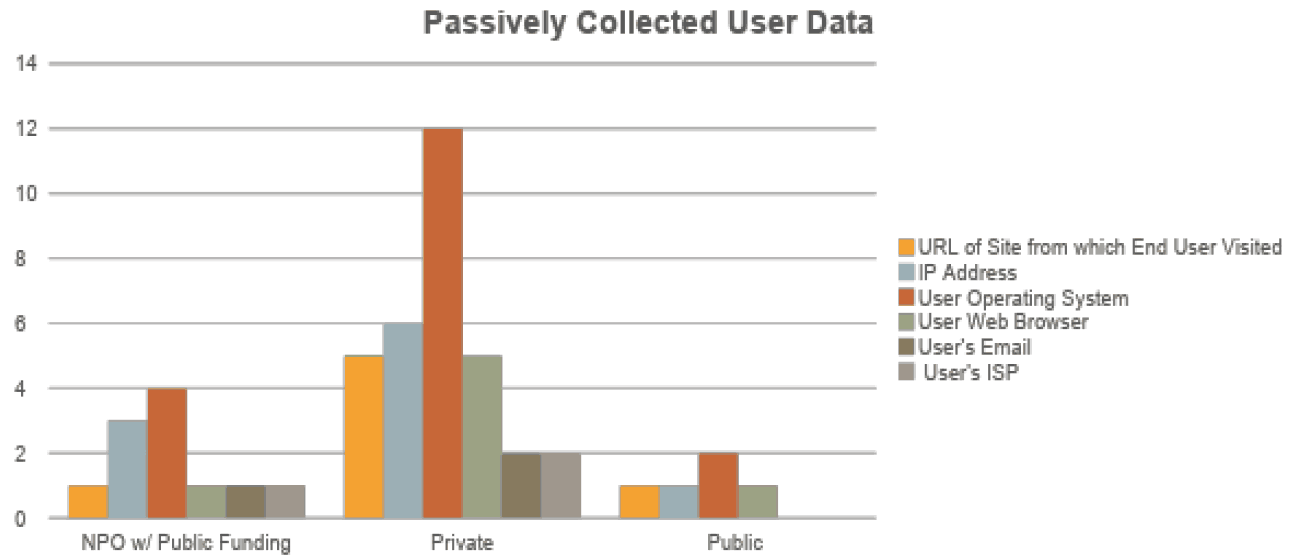

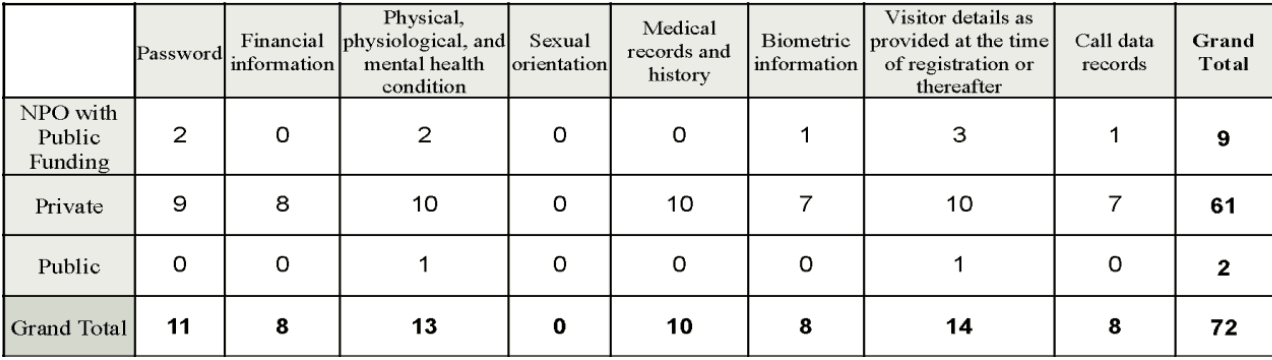

Private eHealth services collected both active and passive data more frequently than public or non-profit eHealth services.

Figure 4: Frequency measurement of passively collected user data, grouped by business model.

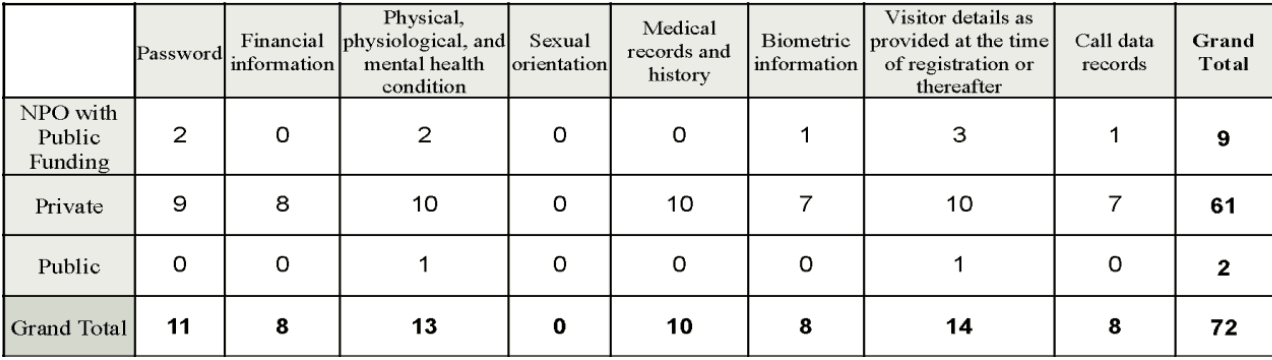

Actively Collected User Data

Figure 5: Frequency measurement of actively collected user data, grouped by business model.

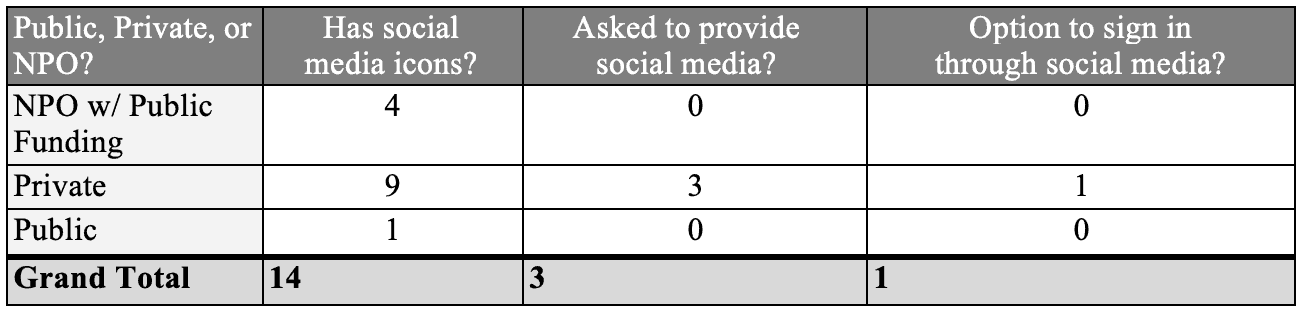

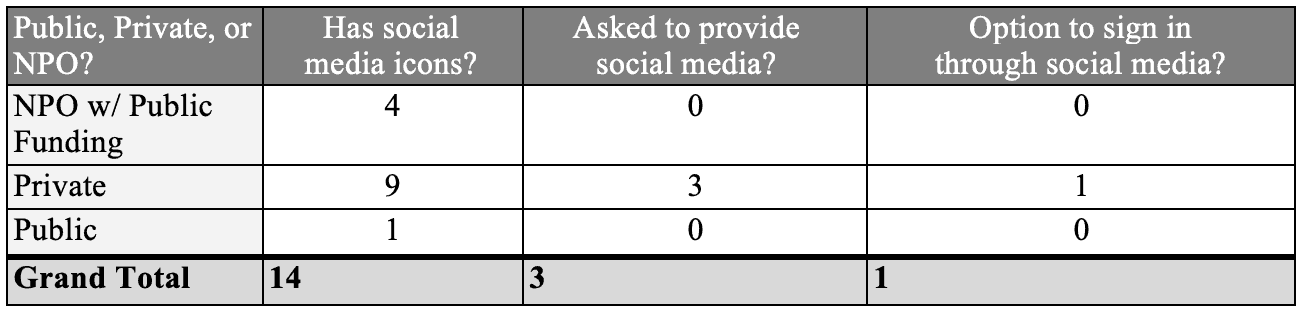

Social Media

Only one service (YourDoctors.Online) allowed for sign-in through a third-party social media application. While the use of social media by these eHealth services could simply be viewed as a marketing or communication tactic, having users connect their social media accounts with these services may also present a further opportunity for data collection. One service directly requested social media information from users (GOeVisit) and two had an app available for download through a Google Play or an Apple account (Livecare and Maple) which would then be connected to other social media information (i.e. Google +).

Figure 6: Depth of social media engagement that services presented, grouped based on business model.

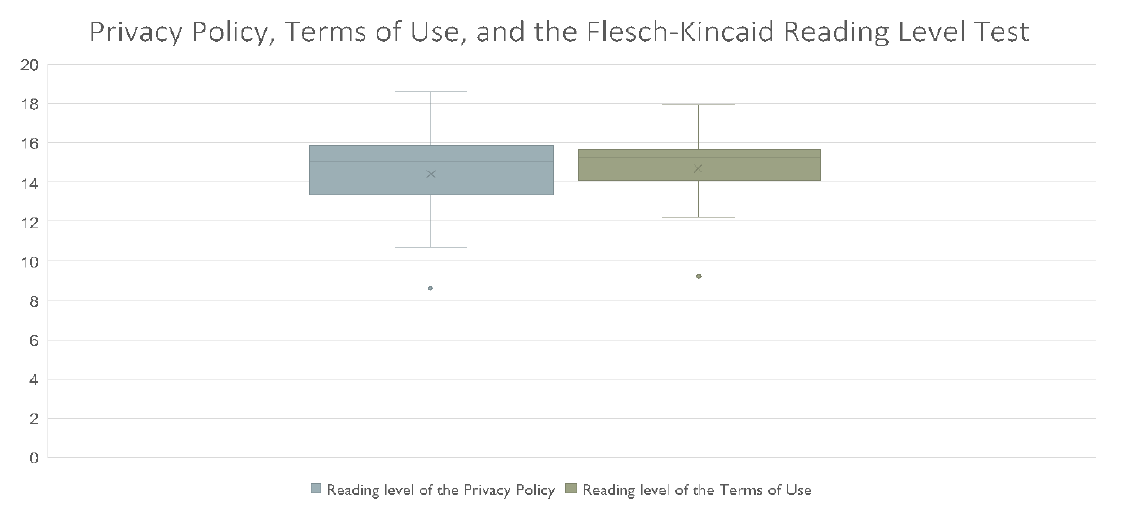

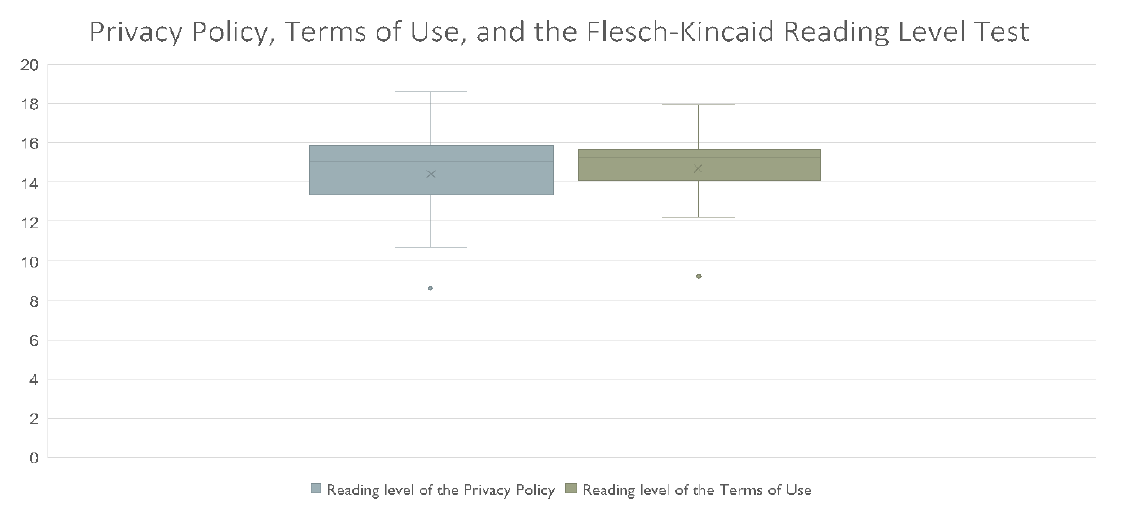

Privacy Policy, Terms of Use, and the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level Test

Seventy-two percent of the services had privacy policies that were accessible from the home page. Sexualhealthontario, MDKonsult, and Ask The Doctors had neither a Privacy Policy nor a Terms of Use agreement.

The measures of central tendency for the Privacy Policies and Terms of Use show that both provisions tended to be similarly difficult to read and were often written above a high school reading level. Privacy policy scores and measures of central tendencies were calculated based on the 14 services that had privacy policies. Sexualhealthontario, youthspace.ca, MDKonsult, and Ask The Doctor did not have privacy policies and thus were factored out.

Terms of Use scores and measures of central tendencies were calculated based on the 13 platforms that had Terms of Use agreements. Sexualhealthontario, Medicuro, Mental Health Helpline, MDKonsult, and Ask The Doctor did not have Terms of Use agreements.

One service, GOeVISIT, had some problematic data policies, such as the note that the service uses both FaceTime and Skype which are not bound by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States and that their data were stored by Rogers. This service did, however, make note that they employ a Privacy Officer. Whether or not the Privacy Officer offsets the possibility for data leakage is a point for ethical consideration.

Privacy Policy: Range = 8.6-18.6, median =15.1 and mean = 14.4; Terms of Use: range = 9.2- 17.9, median=14.7 and mean =15.4.

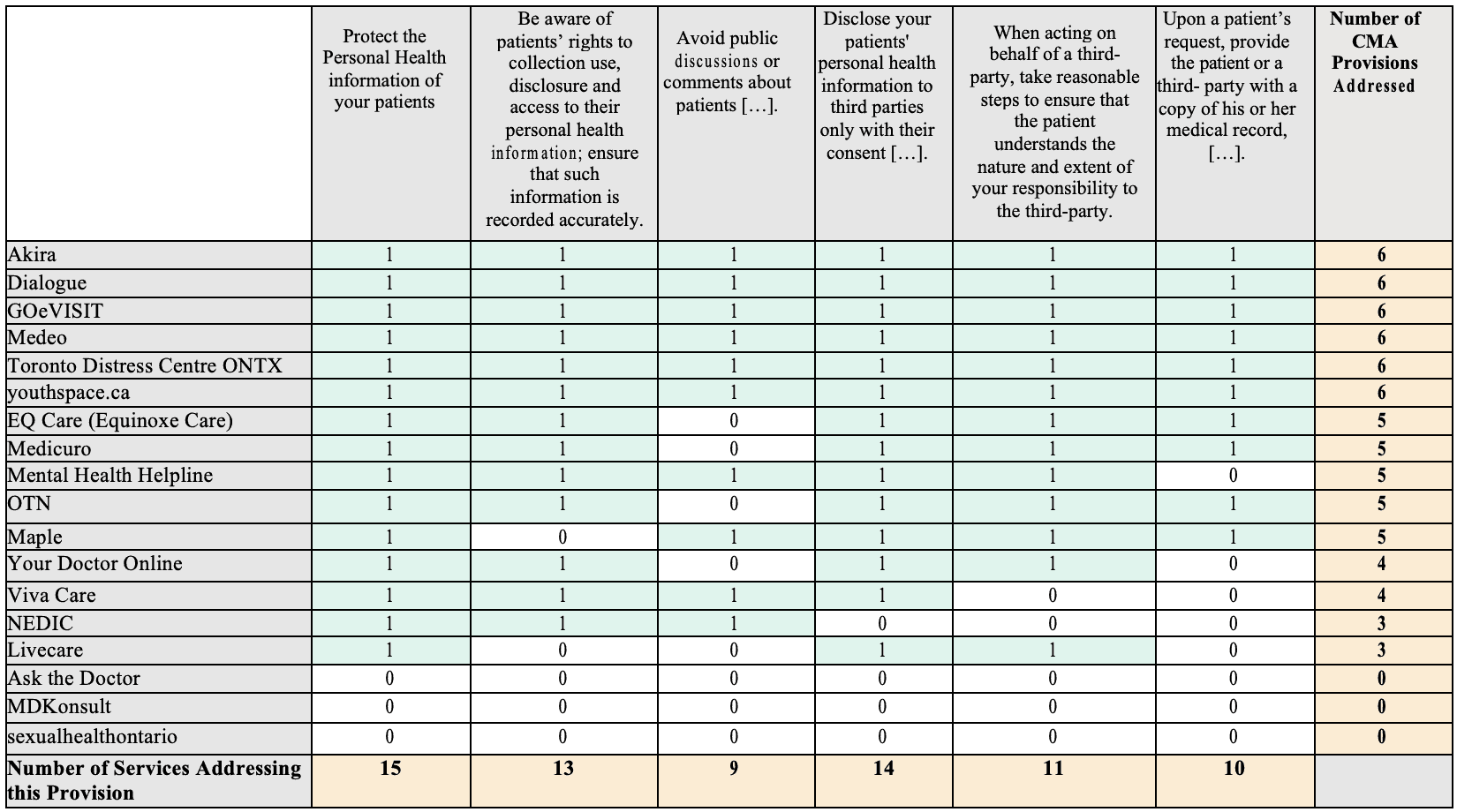

Canadian Medical Association Code of Ethics

In order to analyze compliance to the CMA’s Privacy Policy, the authors analyzed each service’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use agreement to locate the following ethical code provisions (depicted in Figure 8): protection of personal health information, awareness of patient rights, avoidance of public discussion, disclosure of information to third parties only with consent, action to take steps to inform patients about responsibility to third parties, and providing patients with a copy of medical records upon request. Each item was coded as “one” if the provision was satisfied by the service or coded as “zero” if the provision was not met for any reason (either the item was not addressed in the Privacy Policy or Terms of Use Agreement or the documents were not accessible).

Mean CMA adherence = 4.17 provisions, Median= 5 provisions.

Discussion

CMA’s Privacy and Confidentiality Codes

Of the 15 services surveyed which had an explicit privacy policy, six of these met the CMA’s provisions for Privacy and Confidentiality, while the remaining nine services had privacy statements that met at least half of the CMA provisions. It is important to note that when a service-provider’s policy did not make explicit mention of one of the CMA provisions, it was read as though the service provider was not abiding by the code. While the absence of a provision in the privacy policy does not necessarily mean that the service provider is not abiding by the CMA provisions, this absence is instructive. These policies tend to be quite lengthy and thorough, and so for the clarity of these policies all privacy measures taken ought to be stated explicitly.

As for adherence to specific CMA codes, the services that were examined had a policy that affirmed their general commitment to “Protect the personal health information of [their] patients36.” This code is quite general but the unanimous adherence suggest at the very least, a basic understanding and engagement with privacy concerns. Likewise, all but one service explicitly affirmed that they would only disclose personal information with consent or as required by law and would notify patients of any breaches.

The two codes which were most often unobserved (five of 15 services not mentioning them) were avoiding public discussion of sensitive information and providing patients with a copy of their medical record upon request. LiveCare (Private) and NEDIC (Non-Profit Organization) each failed to explicitly address three of the CMA’s six codes, the most of any of the services with available privacy policies. It is important to note that there seems to be little discernible difference between public or not-for-profit organizations and private companies when it comes to observance of the CMA’s Privacy and Confidentiality Codes.

Business Model

As with any organization, understanding the funding model is intrinsic to understanding how it functions. Our primary concern regarding the funding models was borne out of the popular internet maxim, “[i]f you are not paying for it, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold37.” Of particular concern was the issue that if there was not a clear revenue stream for a service, then perhaps the personal health data of users was at risk of being sold.

While a service may appear to be free for the user, there is the possibility that the owners of the applications may attempt to generate revenue in other ways that the consumer is implicated in but unaware of. Even for these ostensibly “free” private healthcare services, there must be some sort of revenue stream, and if there is no cost for the user, then it is possible the selling of user data could be a source of income. Leontiadis et al.38 found that 77% of the top free mobile applications were supported through targeted ads which required access to personal information, and that 94% of these applications also requested network access, which could potentially result in data being leaked. Since free applications tend to request more privacy permissions than paid applications, it is important to understand how the current advertisement model works.

Of the eHealth services that were surveyed, two were publicly funded, run directly by the Ontario government and offered free of charge (Ontario Mental Health Helpline and Sexual Health Ontario). In these situations, the funding models were quite clear. Beyond these publicly administered services, there were four services which were run by independent, not-for-profit organizations (NEDIC, Toronto Distress Centre, youthspace.ca and OTN). Of these four not-for- profits, OTN is the only one that is funded exclusively by the provincial government. The other three services are funded with a mix of grants (public and private), private donation, and corporate sponsorship including Dove, Bell Canada and RBC for NEDIC, Hydro One Inc. and TD Bank Group for the Toronto Distress Centre and Canada Post for youthspace.ca39 40 41.

The remaining 12 services surveyed were privately funded, for-profit organizations. Of these 12, seven of the services (Maple, EQ Care, YourDoctors.online, Medicuro, MDKonsult, Akira, Ask the Doctor) charged patients a clear fee for each consultation ranging between $15 and $150. Dialogue has a similar fee-based model except, in this case, the fees are paid by the employer. Similarly, the fees for Livecare and Medeo are paid by healthcare providers in order to have access to “resources and support to help [them] maximize revenue42.” Lastly, Viva Care and GOeVisit are private companies which provide service to any patients with provincial healthcare coverage. While there is no direct fee for Canadian residents to use GOeVisit, non- Canadians can also access the service for $49.95 per consultation43. Advertisements were relatively rare with only the privately-operated Livecare and Viva Care utilizing them.

While the presence of a clear revenue stream does not preclude the selling of a user data, a lack of evidence of fee or grant based revenue streams should raise a red flag.

Accessibility of Privacy Information

As previously mentioned, the protection of personally identifiable health-related information has traditionally been held to very high standards. There are strict regulations surrounding storing and keeping physical and digital health records by medical practitioners and the advent of new technologies like telehealth and eHealth present new challenges to sensitive health information and its protection. While the policies surrounding physical medical charts might be quite straightforward, things begin to get more complex with eHealth and the inclusion of video conference recordings or chat logs.

When dealing with any sensitive information, the disclosure of privacy policies is critical to the patient’s understanding of what will be done with their information. Having a Privacy Policy and Terms of Use document visible on the homepage of a website signals to the consumer that their privacy is being considered and that the service provider is aware of the serious responsibility that comes with access to such information. While simply having a Privacy Policy and Terms of Use document does not mean that data is necessarily being dealt with appropriately, it does reflect a certain level of awareness and sensitivity.

Of the 18 surveyed services, 12 had both a Privacy Policy and a Terms of Use document, two, Medicuro, Mental Health Helpline, had only a Privacy Policy, one, Youthspace.ca, had a Terms of Use and the remaining three, MDKonsult, askthedoctor, sexualhealthontario had neither. While the presence of one, either a Privacy Policy or a Terms of Use, may be sufficient to ensure patient privacy, services that lacked any visible policies whatsoever were quite concerning.

As stated above, Derse and Miller stressed the importance of physicians only engaging with eHealth services which had defined privacy policies in order to be sure that their patients’ information would remain confidential44. This recommendation for discretion over eHealth services applies to patients as well, since a number of eHealth services examined (namely MDKonsult, Ask the Doctor and sexualhealthontario), do not disclose what will be done with the patient’s information. It is important to note that publicly funded organizations are not necessarily more forthcoming about their data use compared to private organizations as sexualhealthontario, which is a provincial government program, and lacks a privacy policy entirely.

Reading Level of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

An important facet of ensuring privacy policies are accessible is the reading level of the Privacy Policy documents themselves. Having a Privacy Policy and Terms of Use that can be easily found on a service’s website will not be very helpful to users if the documents are full of legal jargon that they cannot understand. Of the documents available, both the mean and the median reading level hovered around grade 14-15 or second-third year of university. While 54% of Canadians between the ages of 25-64 have a post-secondary degree, and could presumably read at this level, a discernible portion of the population would still have difficulty trying to understand these policies45.

Without the ability to read and understand these documents it is difficult for individuals to make informed decisions about their healthcare and the use of their health data. This, of course, is assuming that individuals with a post-secondary education will make it to the privacy policy in the footer of these websites. Many of these sites have sleek and eye-catching designs which require the user to scroll past long pages outlining the benefits of their services, with videos that grab the user’s attention, in order to find the privacy policies at the bottom of the webpage.

Social Media

The majority of the services that were surveyed have social media buttons linking to their various accounts. While the presence of these services on social media and their request (implied or explicit) for users to follow them is not problematic, the request for greater connection between the patient and the healthcare provider increases the amount of data that could possibly be breached.

This is especially pertinent for the services which explicitly involved third-party social media applications. YourDoctors.Online allowed for users to sign-in using an existing Facebook or Gmail account. This is problematic as it links the sensitive health data already held by YourDoctors.Online to further personally identifiable information. Similarly, both Livecare and Maple had apps downloadable through Google Play or Apple accounts again linking the existing data these services hold about a user to data from other online services. These two apps also present additional privacy concerns as they have access to information on your device including images, general storage, camera, and microphone which are implicated in gathering sensitive health information on the platform.

While it does not utilize social media specifically, GOeVisit facilitates its live consultations using Facetime or Skype. The involvement of these third parties is explained in their Privacy Policy which states:

…you assume all risks associated with disclosing your information through Skype™. You understand that, while Skype™ does not warrant that it complies with the HIPAA Security Rule, Skype™ does state that it uses well-known standards-based encryption algorithms to protect Skype™ users’ communications against unauthorized persons. You acknowledge that you have had the opportunity to review information about Skype™’s privacy, available here and its security, available here46.

While GOeVisit is compliant with each of the CMA’s six codes, sensitive health data could still be at risk when it comes into contact with third parties like Skype. Though companies like Skype use encryption, the fact that they are not in the business of securing health data specifically raises ethical concerns about the security of that data.

As more and more parties become involved in healthcare provision, the already complex issue of privacy in eHealth service becomes even more complicated. As seen above in the Skype statement, it is often assumed that the patient has taken the time to read the Privacy Policies and Terms of Use documents for the third parties involved in providing eHealth service, even if the links to these documents are not prominently displayed. Not only does a user have to locate and understand the service provider’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use (if they are available), they must do the same for each of the third-party applications involved.

Further Research

While this study was primarily limited to a Canadian context, eHealth services are becoming more popular around the world. Further research could compare the situation in Canada with eHealth service in other countries. Investigating the difference between eHealth service in a public healthcare setting like Canada and a private system like the United States would be of particular interest. Specifically, in countries with private healthcare systems, citizens who would otherwise have to pay for healthcare may be more likely to turn to a free healthcare application. Studying the data collection and privacy policies of popular eHealth applications in these countries would also be of interest.

Additionally, another direction for future research could include a study that is qualitative in nature which seeks to explore what users of these services understand as personal health data. Such a study could explore understandings of the confidentiality of sensitive health data through the lens of a post-privacy society where data sharing is more prevalent.

Conclusion

In investigating the data we collected on 18 live eHealth chat services hosted in Canada, we came to a number of conclusions about the state of privacy in Canadian eHealth service.

First, that eHealth platforms which had a public-facing Privacy Policy made at least some reference to the CMA’s Privacy and Confidentiality codes. These codes were just updated in 2018 and we believe that they are a helpful starting point for any eHealth services in Canada to begin addressing their Privacy Policies. As such, we recommend that existing and future eHealth service providers strive to meet each of the six codes if they do not already.

We were concerned about the possible sale of patient data by service-providers, and we were encouraged to find that each of the services that we researched had a clear funding model in place. Though this does not necessarily mean that patient data is well protected, we did not have any immediate concerns about the sale of data.

Perhaps the greatest barrier we identified for patients in understanding how their health data would be used was a lack of accessible privacy policies. We separated this notion of accessibility into two parts, the first being the presence of policy documents that can be found on the homepage of the website. While the majority of service-providers had both Privacy Policies and a Terms of Use documents that were easily accessible, it was concerning that three services had no public-facing policy documents whatsoever.

The second part of accessibility relates to reading levels required to read and comprehend these policies. The mean reading level required to read the policy documents accessed was between Grade 14-15 meaning that the roughly 46% of Canadians between the ages of 25-64 who do not have a postsecondary education may be unable to fully understand these documents. We recommend that organizations which are interested in having patients understand their privacy policies, ensure that they are written in plain language and easily understood.

Finally, the integration of social media applications and other third-party service- providers like Skype and Facetime into eHealth services raised ethical concerns for us. While eHealth providers in Canada are bound by strict regulations these third-parties do not necessarily have the same responsibilities. When third-party involvement is unavoidable, we recommend that the primary eHealth provider be as open as possible about privacy policies.

Works Cited

blue_beetle. 2010. “User-driven discontent.” MetaFilter. Accessed 2018 March. https://www.metafilter.com/95152/Userdriven–discontent#3256046.

Boyer, C. 2012. “The Internet and Health: International Approaches to Evaluating the Quality of Web-Based Health Information. In C. George, D. Whitehouse, & P. Duquenoy, eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges.” 245-274. Berlin: Springer.

Canada’s Health Informatics Association. 2012. ” Health Informatics Professional Core Competencies.” Canada’s Health Informatics Association. November. https://digitalhealthcanada.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Health-Informatics-Core- Compet.

Canadian Medical Association. 2018. CMA Policy: CMA Code of Ethics (Update 2004). March.

Accessed March 2018. https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets- library/document/en/advocacy/policy- research/CMA_Policy_Code_of_ethics_of_the_Canadian_Medical_Association_Update_ 2004_PD04-06-e.pdf

Carey, M. 2001. “The Internet Healthcare Coalition: eHealth Ethics Initiative.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 101(8), 878.

Chaet, D., R. Clearfield, J. E. Sabin, and K. Skimming. 2017. ” Ethical practice in Telehealth and Telemedicine.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(10), October: 1136–1140.

Denecke, K., P. Bamidis, C. Bond, E. Gabarron, M. Househ, A. Lau, and M. Hansen. 2015. “Ethical Issues of Social Media Usage in Healthcare.” Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 10(1), 137-147.

Derse, A. R., and T. E. Miller. 2008. “Net Effect: Professional and Ethical Challenges of Medicine Online.” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 453-464.

Di lorio, C. T., and F Carinci. 2013. “Privacy and Health Care Information Systems: Where is the Balance?” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 77-105. Berlin: Springer.

Distress Centres. 2016. “Distress Centres 2016 Annual Report.” Distress Centres. Accessed March 2018. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a03516264b05fad2cec401c/t/5a15e64871c10b644 b17793e/1511384651949/DC-Annual-Report-2016.pdf.

Dobby, Christine. 2013. “More than 90% of Canadians Can’t Get Enough of Google Poll.” Financial Post. January 07. Accessed 2018. http://business.financialpost.com/technology/more-than-90-of- canadians-cant-get – enough-of-google-poll.

Duquenoy, P., Mekawie, N. M., & Springett, M. 2012. “Patients, Trust and Ethics in Information Privacy eHealth.” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 275-295. Berlin: Springer.

Dyer, K. A. 2001. “Ethical Challenges of Medicine and Health on the Internet: A Review.”

Journal of Medical Internet Research, April-June.

Eysenbach, G., G. Yihune, K. Lampe, P. Cross, and D. Brickley. 2000. “Quality management, certification and rating of health information on the Net with MedCERTAIN: using a medPICS/RDF/XML metadata structure for implementing eHealth ethics and creating and rating of health information on the Net…” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2E1.

Fleming, D. A., K. E. Edison, and H Pak. 2009. “Telehealth ethics.” Telemedicine Journal and e- Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 797-803.

Geangu, I. P., D. A. Gârdan, and O. A. Orzan. 2014. “Medical Services Consumer Protection in the Context of eHealth Development.” Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice 6 (1): 473-482.

GOeVisit. 2018. “How it Works.” Accessed March 2018. https://goevisit.com/how-it-works Government of Canada. 2010. “eHealth.” Government of Canada. August 9.

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/ehealth.html Information and Communications Technology Council. 2009. “eHealth in Canada Current

Trends and Future Challenges.” Information and Communications Technology Council. April. https://www.ictc–ctic.ca/wp- content/uploads/2012/06/ICTC_eHealthSitAnalysis_EN_04-09.pdf.

Kaplan, B., and S Litewka. 2008. “Ethical challenges of telemedicine and telehealth.” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 401-416.

Khoja, S., H. Durrani, and P. F Nayani. 2012. “Scope of Policy Issues in eHealth: Results From a Structured Literature Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, E34.

Kleinpeter, E. 2017. “Four Ethical Issues of “E-Health”.” Irbm, 245-249.

Lee, L. M. 2017. “Ethics and subsequent use of electronic health record data.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 143-146.

Leontiadis, I., C. Efstratiou, M. Picone, and C Mascolo. 2012. “Don’t kill my ads! Balancing privacy in an ad-supported mobile application market.” 12th Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems & Applications. San Diego, CA: HotMobile ’12.

Liang, B., T. L. Mackey, and K. M. Lovett. 2011. ” eHealth Ethics: The Online Medical Marketplace and Emerging Ethical Issues. Ethics in Biology, Engineering and Medicine.” 253-265.

Livecare. 2018. ” Home.” https://www.livecare.ca/connect

Michalopoulos, S. 2016. “E-health and the ‘fine line’ of big data.” Euractiv. December 15. https://www.euractiv.com/section/health-consumers/news/special-report-e-health-and- the-fine-line-of-big-data/.

Microsoft. 2018. “Test your document’s readability.” Office Support. Accessed March 2018. https://support.office.com/en-us/article/Test-your-document-s-readability-85b4969e- e80a-4777-8dd3-f7fc3c8b3fd2# toc342546558

MyCare MedTech Inc. 2018. “Privacy Policy.” https://goevisit.com/privacy-policy NEDIC. 2014. “Funding and Community Partners.” http://nedic.ca/about/funding-and-community-partners.

NEED2. 2016. “Funders.” https://need2.ca/funders/.

Razmak, J., and C. H. Bélanger. 2017. “Comparing Canadian physicians and patients on their use of e-health tools.” Technology in Society, 102-112.

Rippen, H., and R. Ahmad. 2000. “e-Health Code of Ethics.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, April: E9.

Rodwin, M. A. 2010. “Patient data: property, privacy & the public interest.” American Journal of Law & Medicine, 586-618.

Samavi, R., and T. Topaloglou. 2008. “Designing Privacy-Aware Personal Health Record.” In ER Workshops, 12-21. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Soenens, E. 2008. “Identity Management Systems in Healthcare: The Issue of Patient Identifiers.” IFIP AICT 298: The Future of Identity in the Information Society, 55-66.

StatCounter. 2018. “Search Engine Market Share in Canada.” March. http://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/canada.

Statistics Canada. 2013. “Canadian Internet use survey, Internet use, by age group, Internet activity, sex, level of education and household income.” Statistics Canada. October 28. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=3580153&&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=31&tabMode=dataTable&csid=.

—. 2017. “Education in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census.” Statistics Canada. from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/171129/dq171129a-eng.htm.

Wadhwa, K., and D. Wright. 2012. “eHealth:Frameworks for Assessing Ethical Impacts.” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and Duquenoy, 183-210. Berlin: Springer.

Webster, P. C. 2010. “Canada’s ehealth software “Tower of Babel”.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, December 14.

Whitehouse, D., and P. Duquenoy. 2008. “Applied Ethics and eHealth: Principles, Identity, and RFID.” IFIP AICT 298: The Future of Identity in the Information Society, 43-55.

Winkelstein, P. 2012. “Medicine 2.0: Ethical Challenges of Social Media for the Health Profession.” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 227-243. Berlin: Springer.

Geangu, P., D. A. Gârdan, and O. A. Orzan. 2014. “Medical Services Consumer Protection in the Context of eHealth Development.” Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice 6 (1): 473-482.

Statistics Canada. 2013. “Canadian Internet use survey, Internet use, by age group, Internet activity, sex, level of education and household income.” Statistics Canada. Accessed October 28. https://goo.gl/sbzMVZ.

Geangu, Gârdan, & Orzan, 2014, p.

Government of Canada. 2010. “eHealth.” Government of Canada. Accessed August 9.https://goo.gl/JFX5bS.

Webster, P. C. 2010. “Canada’s ehealth software “Tower of Babel”.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182 (18). Accessed March 2018. http://www.cmaj.ca/content/182/18/1945

Chaet, D., R. Clearfield, J. E. Sabin, and K. Skimming. 2017. ” Ethical practice in Telehealth and ”

Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(10), October: 1136–1140.

Razmak, J., and C. H. Bélanger. 2017. “Comparing Canadian physicians and patients on their use of e-health tools.” Technology in Society Volume 51: 102-112.

Canada’s Health Informatics Association. 2012. ” Health Informatics Professional Core Competencies .” Canada’s Health Informatics Association. Accessed November 2018. https://digitalhealthcanada.com

Information and Communications Technology 2009. “eHealth in Canada Current Trends and Future Challenges.” Information and Communications Technology Council p. 5. Accessed April 2018. https://goo.gl/cGgg9q

Khoja, , H. Durrani, and P. F Nayani. 2012. “Scope of Policy Issues in eHealth: Results From a Structured Literature Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research Volume 14, Issue 1 p.E34.

Dyer, K. A. 2001. “Ethical Challenges of Medicine and Health on the Internet: A Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 3(2) E23.

Duquenoy, P., Mekawie, N. M., & Springett, M. 2012. “Patients, Trust and Ethics in Information Privacy eHealth.” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 275-295. Berlin: Townsend, A., Leese, J., Adam, P., McDonald, M., Li, L. C., Kerr, S., & Backman, C. L. (2015). “eHealth,

Participatory Medicine, and Ethical Care: A Focus Group Study of Patients’ and Health Care Providers’ Use of Health-Related Information.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(6), e155.

Fleming, D. A., Edison H. A, and Pak, A. 2009. “Telehealth ethics.” Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, (15)8 p. 797-803.

Kaplan, B., and Litewka, S. 2008. “Ethical challenges of telemedicine and telehealth.” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, (17), Issue 4 p. 401-416.

16 Chaet, et al. 2017. p.1136–1140.

Whitehouse, D., and P. Duquenoy. 2008. “Applied Ethics and eHealth: Principles, Identity, and RFID.” IFIP AICT 298: The Future of Identity in the Information Society, 43-55.

Samavi, R., and T. Topaloglou. 2008. “Designing Privacy-Aware Personal Health Record.” In ER Workshops, 12-Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Wadhwa, K., and D. Wright. 2012. “eHealth:Frameworks for Assessing Ethical Impacts.” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 183-210. Berlin: 20 Soenens, E. 2008. “Identity Management Systems in Healthcare: The Issue of Patient Identifiers.” IFIP AICT 298: The Future of Identity in the Information Society, 55-66.

Derse, A. R., and T. E. Miller. 2008. “Net Effect: Professional and Ethical Challenges of Medicine Online.”Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 17(4) 453-464.

Di lorio, C. T., and F. Carinci. 2013. “Privacy and Health Care Information Systems: Where is the Balance?” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 77-105. Berlin: Springer.

Boyer, C. 2012. “The Internet and Health: International Approaches to Evaluating the Quality of Web-Based Health Information. In C. George, D. Whitehouse, & P. Duquenoy, eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges.” 245-274. Berlin:

Rodwin, M. A. 2010. “Patient data: property, privacy & the public interest.” American Journal of Law & Medicine, 586-618.

Kleinpeter, E. 2017. “Four Ethical Issues of “E-Health”.” IRBM, 38(5) 245-249.

Lee, L. M. 2017. “Ethics and subsequent use of electronic health record data.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics, Volume 71 143-146.

Winkelstein, P. 2012. “Medicine 2.0: Ethical Challenges of Social Media for the Health Profession.” In eHealth: Legal, Ethical and Governance Challenges, by C. George, D. Whitehouse and P. Duquenoy, 227-243. Berlin: Springer.

Liang, B., T. L. Mackey, and K. M. Lovett. 2011.” eHealth Ethics: The Online Medical Marketplace and

Emerging Ethical Issues. Ethics in Biology, Engineering and Medicine,p 253-265; Denecke, K., P. Bamidis, C. Bond, E. Gabarron, M. Househ, A. Lau, and M. Hansen. 2015. “Ethical Issues of Social Media Usage in Healthcare.” Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 10(1), p.137-147.

Michalopoulos, S. 2016. “E-health and the ‘fine line’ of big data.” Euractiv. Accessed March https://goo.gl/PrXN2X.

Khoja et al. 2012.

Canadian Medical Association. 2018. CMA Policy: CMA Code of Ethics (Update 2004). March. Accessed March 2018. https://goo.gl/RBkrnS

Canadian Medical Association.

2018. “Search Engine Market Share in Canada.” Accessed March 2018. http://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/canada.; Dobby, Christine. 2013. “More than 90% of Canadians Can’t Get Enough of Google: Poll.” Financial Post. January 07. Accessed 2018. https://goo.gl/HtgcP2 34 Microsoft. 2018. “Test your document’s readability.” Office Support. Accessed March 2018. https://goo.gl/AcPxro.

Canadian Medical Association.

2010. “User-driven discontent.” MetaFilter. (Blog comment). Accessed 2018 March. https://www.metafilter.com/95152/Userdriven-discontent#3256046.

Leontiadis, I., C. Efstratiou, M. Picone, and C Mascolo. 2012. “Don’t kill my ads! Balancing privacy in an ad-supported mobile application market.” 12th Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems & Applications. San Diego, CA: HotMobile ’12.

2018. “How it Works.” Accessed March 2018. https://goevisit.com/how-it-works.

Distress Centres. 2016. “Distress Centres 2016 Annual Report.” Distress Centres. Accessed March https://goo.gl/JiWKud.

2016. “Funders.” https://need2.ca/funders/.

2018. ” Home.” https://www.livecare.ca/connect.

Derse, A. R., and T. E. Miller. 2008. “Net Effect: Professional and Ethical Challenges of Medicine Online”. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 453-464.

Statistics Canada. 2017. “Education in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census.” Statistics Canada. from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171129/dq171129a-eng.htm

MyCare MedTech Inc. 2018. “Privacy Policy.” Accessed March 2018. https://goevisit.com/privacy-policy.

Information Technology and Modern Public Service:

How to Avoid IT Project Failure and Promote Success

Scarlett Kelly

Table of Content

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2

Background……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2

What are IT project failures and IT projects success?……………………………………………………………. 3

The factors that determine IT project failures……………………………………………………………………….. 5

People…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6

Process……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7

Product……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11

Case study……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 12

Recommendations for promoting IT projects success………………………………………………………….. 13

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 15

References……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 17

Introduction

Successful information technology (IT) projects have the potential to support and transform governmental functions to a higher level of efficiency and cost-effectiveness when delivering services to end-users.1 In this sense, the ideal state is that successful IT projects have the potential to improve public service functions and deliver services to citizens more efficiently and cost effectively.2 However, a global scan shows that IT projects have as high as 85% failure rates and only 15% success rates.3

The reality is that Canada seldom receives such benefits because of the repeated IT project failures and many unanswered questions behind these failures. How can we define IT project failures and successes? Who are the most important stakeholders in any IT project? Facing the negative consequences of IT project failures, especially the financial burden, is the purpose of this paper which performs an in-depth analysis of IT project failure/success factors with real-life examples, including the Phoenix pay system4 as a case study.

To answer the research question “what are the factors that contribute to the success or the failures of IT projects in governments,” this paper will examine the three key factors of IT projects — the people involved, IT processes (purpose of the project, planning, and implementation with a focus on external/internal management), and product to deliver to users. After presenting a holistic understanding of IT project failures, this paper will make actionable recommendations in the Canadian context for promoting IT project success.

Based on the research done to date, the key finding is that many of the IT projects are politically motivated and departmental staff expertise is often overlooked. Lack of leadership and sufficient in-house IT knowledge appears to have made governments make decisions by instinct, so the failure of linking IT products with the internal departmental function becomes inevitable.

Background

The application of IT in the government fundamentally changed the government in no less a way than the French revolution reshaped Europe or printing technology shaped the western civilization.5 6 Electronic government, or e-government provides a channel for citizens to directly communicate with the government in an online environment, which enhances citizen engagement, provides new information presentation, and consultation.7 However, IT projects do not always return benefits. The Auditor General of Canada (Auditor General) found that in the Department of National Defence (DND), IT project implementation took on average seven years after a long seven-year funding approval.8 Moreover, by 1994 about $1.2 billion out of $3.2 billion in the IT program budget was not supported by a plan that monitors expenditure and the implementation process, and $700 million could have been saved if 11 projects had been implemented based on priority.9

In addition to the technology failure, IT disruptions frequently happens because of:

- the failure of planning, managing and decision-making when implementing IT products;

- the lack of control and risk 10

Three main factors contribute to the IT failure or success in the government—people, process and product.11

- People include government departments, external stakeholders, and citizens/end-users.

- The IT project process begins with finding the right project and ends with implementing the project within a specific timeline. In other words, the IT process is a business process which includes defining the purpose of introducing IT products (the question why), listing all the desired features of the product, purchasing or manufacturing the product by establishing partnerships with the private sector, developing a detailed and complete implementation plan (financing, deadlines, evaluation, and accountability), managing the implementation both internally and externally, and delivering a functioning final product. Both senior management commitment and project management play vital roles in the IT process because of the complex relations between the public and private sectors as well as the considerations within the government and with end-users, which will be discussed in detail in the “process” section.

- Product includes the technology selected for users and its performance

The three components are inter-related; for example, when people fail to work together and develop a common goal, the IT process will not go smoothly and meet the goals all stakeholders agreed upon. The obstacles in the IT product implementation process can lead to malfunctioning projects which directly result in the final products not meeting the needs of the stakeholders. However, this relationship is not linear. For example, any problems in the process could change the relations among the people involved, which can change the final product and the performance evaluation framework. All these will be discussed in detail in the next few sections of this paper.

What are IT project failures and IT project successes?

IT project success is defined as most/all stakeholder groups having attained their major goals and there are no significant undesirable outcomes of IT process and products. 12 Such success is achieved by following project schedules, staying in budget, and delivering a final IT product that functions fully as expected. No part in the people, process, and product IT project lifecycle can fail.

The opposite of IT project success, IT project failure, can be defined as project outcomes are not what stakeholders initially expected. Such failure is caused by fragmented planning and mistakes in implementation, project management, and decision-making. These may include, ignoring stakeholders’ needs or the departmental operations that are less ideal for IT product implementation and management, where control and risk prevention are lacking.13 IT project failures can result in delayed schedules, high costs, system uselessness and/or reliability problems, 14 and worst of all, the loss of public confidence in government’s ability and accountability when handling taxpayer’s money. Fear of potential IT project failure can make governments hesitate when considering introducing IT products or deciding not to adopt IT products to eliminate risks. Therefore, IT failure could result in a vicious cycle: less innovation in IT projects due to fear, less effort put into IT projects because of the repeated and perceived failure, and less chance for success.

One of the many examples of IT project failure is the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s attempt to build a fully integrated system, Agconnex, for farmers which resulted in a $14 million failure.15 Another example is the Automated Land and Mineral Record System (ALMRS) system in the U.S., which aimed to improve the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) ability to record, maintain, and retrieve information on land description and ownership. ALMRS’s major software component—Initial Operating Capability (IOC)—failed to meet BLM’s needs and was not deployable. 16 This is because BLM failed to strengthen its investment management system acquisition processes and an overall project plan and timeline for actions.17 After spending $411 million, including $67 million spending on the IOC software development, the project was terminated in 1998.18

The factors that determine IT project failures

Introducing IT products to organizations is not a linear technological change but involves complex human factors. 19 Three main factors—people, process, and product—contribute to IT project failure or success in governments. 20 Any interruptions in the people, process, and product implementation stages can result in ripple effects and eventually the project’s failure. For example, when there is stakeholder resistance, reaching a common goal and developing plans becomes more difficult. Such resistance also results in delays in project scheduling and difficulty in managing the IT implementation. There are no sequential relationships: any delay in the schedule can result in difficulty in management which then affects stakeholder and user confidence, as demonstrated in the graph below.

People

As the initial step that leads to IT project failures/successes, the people factor includes government departments, external/private sector stakeholders, and citizens/end-users. 21 The quality of departmental collaboration, stakeholder support/resistance and end-users’ comments on product functionality requirements can all become factors in the potential IT project failure/success.

First, the quality of departmental collaboration can initiate smooth IT planning, but the lack of an effective cross-departmental IT strategy and working governance can be a problem.22 For example, the Sustainable Access in Rural India (SARI) project in Tamil Nadu, India, was an e-government project that used a Wireless-in-Local Loop (WLL) technology to provide internet connections to 39 rural villages in the region.23 A lack of clearly defined goals appeared from the beginning—the program only transformed applications from paper-based to electronic submission without changing the traditional less-transparent back-office operations.24 Such a product did not meet the end-users’ expectations; only 12 villages used the service regularly.25 Furthermore, there was no cross functional service delivery framework due to the lack of collaboration with other levels of government and the failure continued in the long run. 26 There was also no sustained public leadership and commitment, either: the involved officials and staff constantly changed and there was no consistent support for the new technology which induced changes in the traditional roles, authorities and network.27

Second, the development of IT projects often involves multiple stakeholders who have different management styles and goals. 28 Their willingness to collaborate directly affects the project success or failure. For example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the U.S. is responsible for the security of cyber space. Its programs are aimed at recovery efforts for public and private internet systems, identifying laws and regulations regarding recovery in the event of a major internet disruption, evaluating plans for recovery, and assessing challenges.29 Clarification of roles and responsibilities is crucial because in the course of internet recovery, the private sector owns and operates the majority of the internet.30 Yet there was no consensus among public and private stakeholders about what DHS’ role was or when it should get involved.31 The private sector was reluctant to share information on internet performance with the government, but the government could only take limited actions due to legal issues.32 Such lack of stakeholder engagement directly resulted in the DHS programs failure.

Third, end-users are one of the most crucial components, since their approval of service quality and product functionality indicates the success of IT projects. Meeting end-user’ performance expectations, such as system usefulness and information quality, becomes key to earning their approval on the technology deliverable. Romania’s e-government success largely depended on how its services meet the citizens’ needs of usefulness, ease of use and quality and trust of e- government services.33 In this sense, IT products’ ability to influence citizens’ choices, offer personalized services, and build trust become three pillars to make citizens accept IT products.34

Process