Sagesse: 2020 Edition Volume V

Sagesse 2020, Volume V, Issue I

1-Introduction [web link] [pdf]

2- Achieving Perfect PITCH [web link] [pdf]

3- Our Phygital World and Information Management [web link] [pdf]

4- Preserving the Legacy of Residential Schooling Through a Rawlsian Framework [web link] [pdf]

5- Préserver l’héritage des pensionnats indiens en s’appuyant sur les principes de Rawls [web link] [pdf]

6- The Transformational Impacts of Big Data and Analytics [web link] [pdf]

7- Les effets transformateurs des mégadonnées et del’analytique [web link] [pdf]

8- Tribute to Leonora Casey [web link] [pdf]

9- Smart wearables and Canadian Privacy: Consumer concerns and participation in the ecosystem of the Internet of Things (IoT) [web link] [pdf]

10- In memory of Ivan Saunders… [web link] [pdf]

White Papers 2020

Whitepaper– Integrate Digital Preservation into Your Information Governance Program [web link] [pdf]

Whitepaper– Case Study: Migrating a Billion-Dollar Government Agency to a New Records System [web link] [pdf]

Introduction

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes. Contains 1200 words

Welcome to ARMA Canada’s fifth issue of Sagesse: Journal of Canadian Records and Information Management, an ARMA Canada publication.

Sagesse’s Editorial Team

Sagesse’s Editorial Board welcomes Barbara Bellamy, CRM, as ARMA Canada’s Director of Canadian Content, effective July 1, 2020. Barbara has a wealth of ARMA experience, at the Chapter level with her volunteer work on the ARMA Calgary Chapter as well her contributions to ARMA International’s Education Foundation (AIEF). She co-authored an article that appeared in Sagesse’s 2019 edition (see “Email Policy and Adoption”) and is a regular speaker at ARMA Canada conferences. Barbara has already taken a leading role with moving Sagesse forward as you will see in reading this edition. She is a most valuable addition to the team. Welcome Barbara.

We also welcome Pat Burns, CRM, to the Sagesse team. Pat also has an extensive resume with ARMA Canada, ARMA International and the ARMA New Brunswick Chapter. She was Chapter President for many years, was ARMA Canada’s Region Director for 4 years and then spent valuable time with ARMA International and the Institute of Certified Records Managers. We are thrilled to work with Pat and have her and her expertise on our team!

Congratulations are extended to Sagesse’s editorial board member Stuart Rennie who received ARMA International’s Company of Fellows distinction (Fellow of ARMA International or FAI) at ARMA International’s conference in 2019 at Nashville. Stuart is the 6th FAI in Canada.

University Essay Contest

ARMA Canada held its second essay contest for graduate students enrolled in graduate information management programs in Canadian universities in 2019. We are pleased to announce that the team of Alissa Droog, Dayna Yankovich, and Laura Sedgwick, from Western University, were the $1,000 recipients with their article “Preserving the Legacy of Residential Schooling Through a Rawlsian Framework.” Their article focuses on what some have called a controversial decision made by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2017 when it ruled that student records from the government’s truth and reconciliation initiative, specifically the Independent Assessment Process (IAP records), which related to how survivors of residential schooling systems were treated, should be destroyed.

The recipient of the $600 award was Emily Speight, from Dalhousie University, for her article, “Smart Wearables and Canadian Privacy: Consumer Concerns and Participation in the Ecosystem of the Internet of Things (IoT).” Her article focuses on the plethora of smart technologies, from smart cars to smart clothing, and the Internet of Things (IoT) potential to revolutionize how we live, yet there appears to be resistance to those technologies. How should that resistance change to improve consumer engagement?

Congratulations to our students!

Sagesse’s New Feature – White Papers

Be sure to check out Sagesse’s newest feature, white papers, published in addition to the Sagesse articles. You’ll find the white papers on the ARMA Canada’s website at https://armacanada.org/, in About Sagesse, https://armacanada.org/portfolio/sagesse/.

In 2019 two white papers were published:

- “Choosing a Software – Getting to the Request for Proposal (RFP),” by Brenda Prowse, CRM, and

- “Bring Order to Chaos: Regaining Control of Unstructured Data,” by Jacques Sauve.

The 2020 edition of Sagesse features the following white papers:

- “Integrate Digital Preservation into your Information Governance Program,” by Lori J. Ashley, and

- “Case Study: Migrating a Billion-dollar Government Agency to a New Records System,” by Jas Shukla.

2020 Sagesse Articles

- Giles Grouch examines “Our Phygital World and Information Management,” and the rapid advances made by information technologies calling that phenomena “a phygital” world or a blend of physical and digital. While he states that our devices, smartphones, laptops, watches, etc., blur the line between personal and work information, new approaches in thinking about information and communication are required.

- In keeping with changes in the business and academic landscape, Christy Walters and Chrystal Walters’ article discusses “The Transformational Impacts of Big Data and Analytics.” Their article looks at an evolving positive view of big data and its transformational impacts on business and discusses the innovative ways data analytics has evolved and how it is transforming today’s business landscape.?

- Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you must briefly and without any visuals present to a group of non-records and information management professionals the value of a retention schedule? Sue Rock, CRM, did, and shares that experience in her article entitled “Achieving Perfect “PITCH.” She also has excellent suggestions on how to prepare the impeccable 30-second sound bite on the role of records in a business setting.

Sagesse’s editorial board would also like to take this opportunity to acknowledge two outstanding members of ARMA Canada’s team who recently passed.

-

Ivan Sanders, see article “In memory of Ivan Saunders,” and

-

Leonora Casey, see article “Tribute to Leonora Casey.”

Both articles appear in this issue of Sagesse. Ivan was for many years ARMA Canada’s Conference Director and a member of ARMA Saskatchewan Chapter. Leonora was ARMA Canada’s webmaster and a member of ARMA Calgary and ARMA Vancouver Island Chapters. We miss them both.

Please note the disclaimer at the end of this Introduction stating the opinions expressed by the authors in this publication are not the opinions of ARMA Canada or the editorial committee. We are interested in hearing whether you agree or not with this content or have other thoughts or recommendations about the publication. Please share and forward to: sagesse@armacanada.org

If you are interested in providing an article for Sagesse, or wish to obtain more information on writing for Sagesse, contact us at sagesse@armacanada.org.

Enjoy!

ARMA Canada’s Sagesse’s Editorial Review Committee:

Christine Ardern, CRM, FAI, IGP; Barbara Bellamy, CRM, incoming ARMA Canada Director of Canadian Content; Alexandra (Sandie) Bradley, CRM, FAI; Pat Burns, CRM; Sandra Dunkin, MLIS, CRM, IGP; Stuart Rennie, JD, MLIS, BA (Hons.), FAI; Uta Fox, CRM, FAI, outgoing Director of Canadian Content.

Disclaimer

The contents of material published on the ARMA Canada website are for general information purposes only and are not intended to provide legal advice or opinion of any kind. The contents of this publication should not be relied upon. The contents of this publication should not be seen as a substitute for obtaining competent legal counsel or advice or other professional advice. If legal advice or counsel or other professional advice is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.

While ARMA Canada has made reasonable efforts to ensure that the contents of this publication are accurate, ARMA Canada does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, currency or completeness of the contents of this publication. Opinions of authors of material published on the ARMA Canada website are not an endorsement by ARMA Canada or ARMA International and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of ARMA Canada or ARMA International.

ARMA Canada expressly disclaims all representations, warranties, conditions and endorsements. In no event shall ARMA Canada, its directors, agents, consultants or employees be liable for any loss, damages or costs whatsoever, including (without limiting the generality of the foregoing) any direct, indirect, punitive, special, exemplary or consequential damages arising from, or in connection to, any use of any of the contents of this publication.

Material published on the ARMA Canada website may contain links to other websites. These links to other websites are not under the control of ARMA Canada and are merely provided solely for the convenience of users. ARMA Canada assumes no responsibility or guarantee for the accuracy or legality of material published on these other websites. ARMA Canada does not endorse these other websites or the material published there.

Achieving Perfect “PITCH”

By Sue Rock, CRM

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes. Contains 2042 words

Introduction

Imagine you are sitting with a panel of records experts, in front of a group of keen Data Architects, and you have just 10 minutes to present the value of a retention schedule. And, you can’t use any visuals. How would you strive to achieve the perfect pitch?

The theme for this article focuses on a case study of how the long-established fundamental of records management, the records retention schedule, was pitched to a group of Data Architects.

The Opportunity

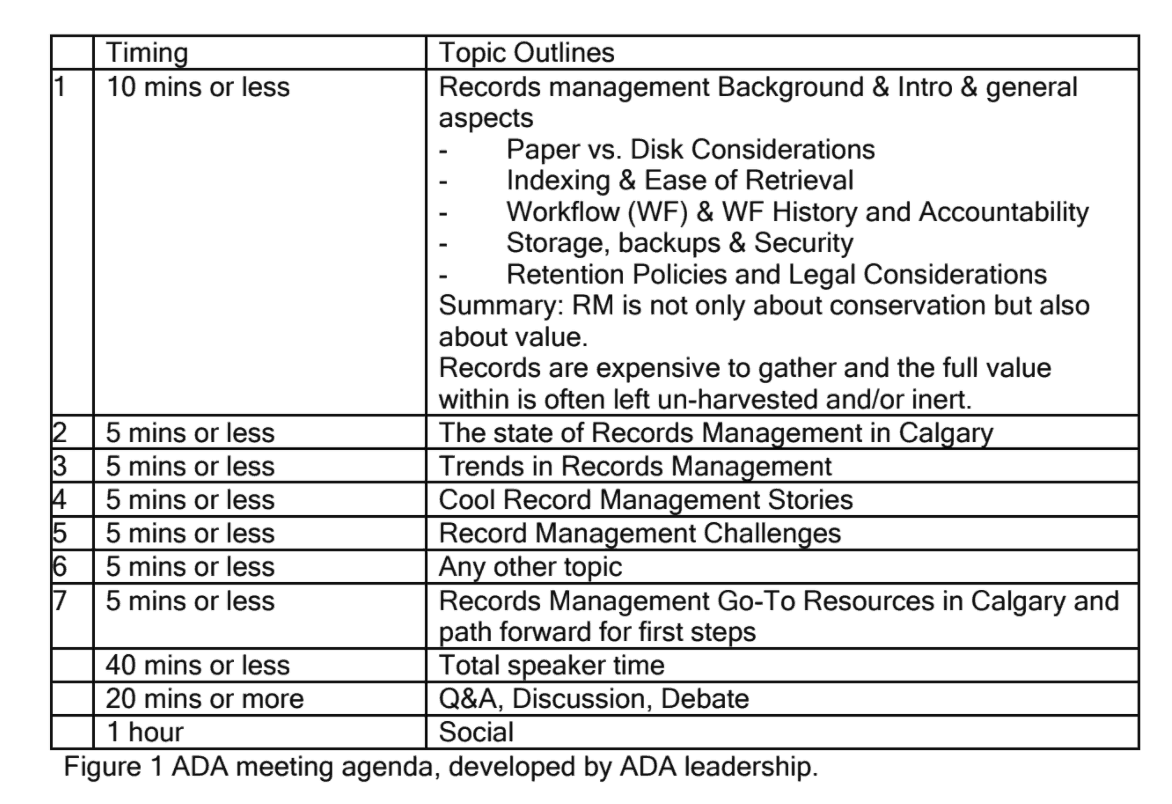

An opportunity was extended to present, among a panel of records managers, the topic ‘Retention Policies and Legal Considerations’ to the Alberta Data Architecture Association (ADA) in “10 minutes or less”.

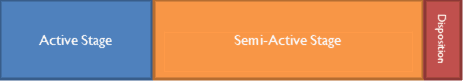

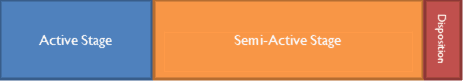

ADA indicated in its outreach that it expected an informal, information sharing session, followed by a social. The invitation specified expectations as illustrated in Figure 1. Stringent as the time allotments were, it was encouraging that the group’s leadership had developed an ambitious plan to receive an overview of records management. Three records managers responded enthusiastically to the invitation.

The Agenda

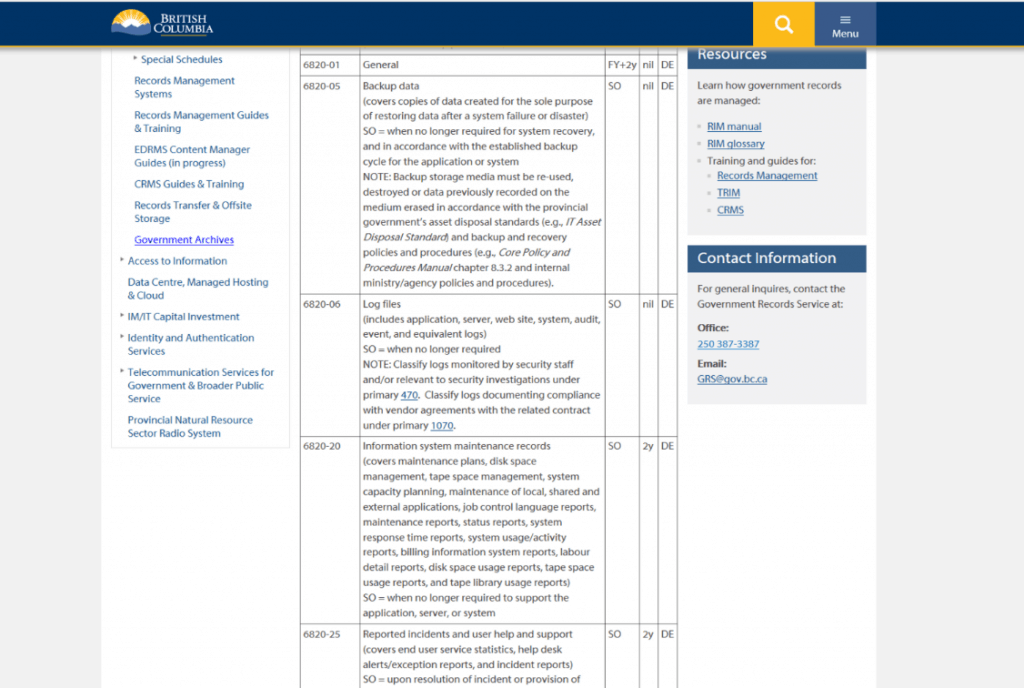

Figure 1 ADA meeting agenda, developed by ADA leadership.

The Challenge

The first step to prepare for a verbal presentation is to define the receiving audience. Which nuggets of retention scheduling would best meet ADA’s expectations? The following definition outlines the general scope of Data Architecture practices.

Data architecture defines the collection, storage and movement of data across an organization … Information architecture refers to the development of programs designed to input, store and analyze meaningful information whereas data architecture is the development of programs that interpret and store data.

Secondly, what are the records management ‘go-to’ resources (Figure 1, Agenda item 7) to share with verbal offerings?

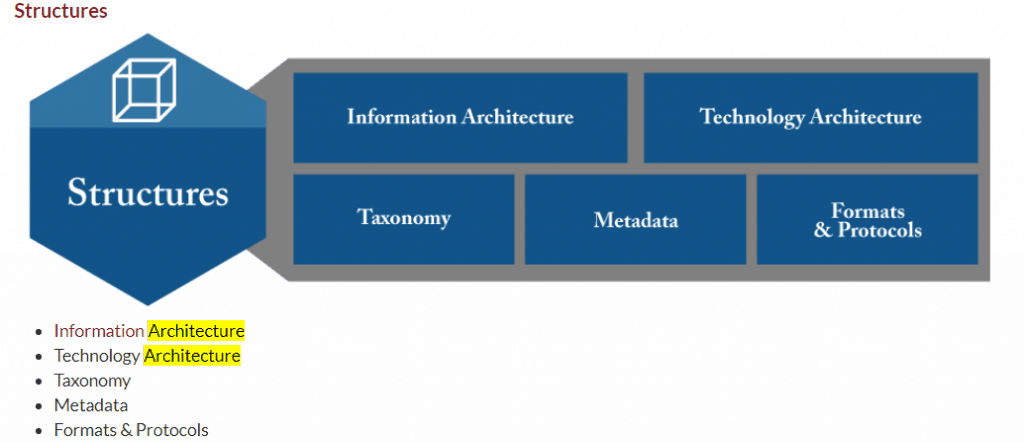

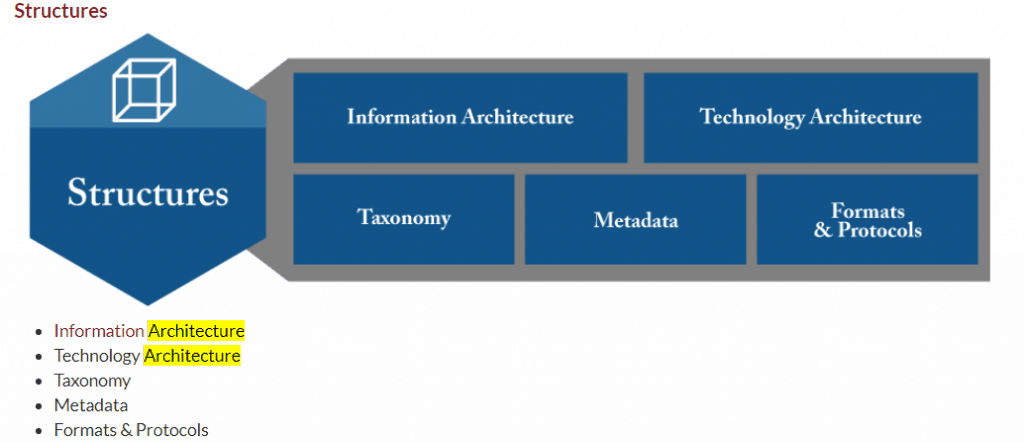

An immediate and useful ARMA resource is the free, five-page document called The ARMA Information Governance Implementation Model (IGIM) which, in November 2019, remained in the BETA publishing stage. Among the seven models which attempt to connect the various stakeholders of Information Governance, the ‘Architecture’ references were displayed within the SUPPORTS function.

The visual bullet points in Figure 2 helped describe the ADA receiving audience – specifically, the terms Taxonomy and Metadata draw records management closer to the realm of Data Architecture. The path to achieving a perfect pitch of retention schedule value became clearer.

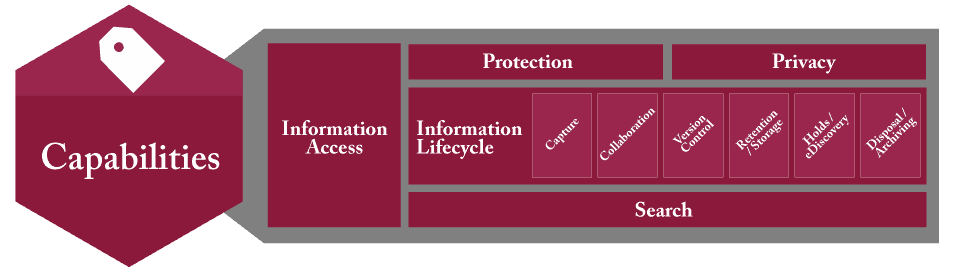

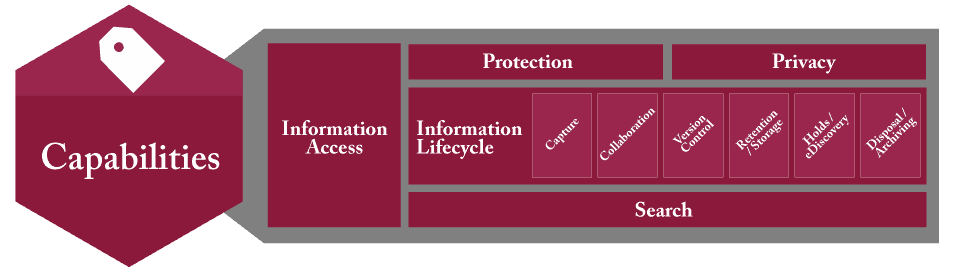

Having located ‘Architecture’ among the IGIM diagrams, further examination of the diagrams led to the role of records retention located under Capabilities within the IGIM model, shown in Figure 3.

Figures 2 and 3 are examples of the type of resources immediately accessible to records managers to share with information management disciplines interested in understanding alignment opportunities.

The Presentation

Although an agenda had been distributed, the presentation itself was quite ‘fluid’. The audience numbers were small; those present were actively engaged. The ADA Chair took on item 1 of the agenda “Records management background” in the allocated “10 minutes or less”, ending on a high note of “RM is not only about conservation but also about value. Records are expensive to gather and the full value within is often left un-harvested and/or inert.”

Three ARMA Calgary Chapter members represented Records Management in Calgary. Within the allotted 5 minutes, the Chapter President deftly addressed the content records management assisted by a gigantic wall chart which very visibly illustrated the record lifecycle. There had been no explicit exclusion of wall charts as visuals within the agenda!

Another RIM practitioner whose banking company fully and aggressively supports Enterprise Content Management entertained the audience with ‘cool stories’ (Figure 1, Item 4) – how their RIM forays and triumphs were achieved using creative technology solutions. His presentation garnered more than 5 minutes, most likely because everyone uses banking services. The audience asked many technology-focused questions, and this bank in particular continues to lead in its implementation of user-oriented technologies which are truly ‘cool’.

The segue from cool technology to records retention was a challenge. Why would a retention schedule be of interest to Data Architects?

A method of setting an audience at ease is to emphasize alignment, in this setting between Data Architecture and RIM practices. This portion of the presentation began by a quick review of Data Architecture’s governance scope, followed by a Records Retention Schedule governance scope to illustrate the parallel.

The presentation began with a question: “Does Data Architecture require governance to track elements such as?” ->

-

Ownership

-

Security/permissions

-

Legislative requirements such as privacy

-

Legal requirements such as

- Trade secret contractual obligations

- Copyright permissions/restrictions;

- Project management contractual obligations

-

Approved data collection sources both internal and external

-

Data transactions within the system

-

System integration with other systems

-

User agreement statuses: current; expired

-

Data distribution agreement statuses: current; expired.

It continued energetically with a summary of how a retention schedule is a governance tool for all business information. It addresses key issues such as:

-

Who owns the records (by business role; department; etc.)?

-

Where are the records located (links to legislative requirements)?

-

What are the legislative requirements, including privacy permissions/restrictions?

-

Are there business legal requirements such as product licensing restrictions, copyright?

-

Who is permitted to use records; who is not permitted to use records?

Having established a point of intersection/alignment, measured by receptive nods and ah’s, the presentation proceeded to explain how aspects of a retention schedule can help Data Architects achieve fundamental objectives.

The ADA agenda timer was on his job! It was urgent to pitch how exactly a records retention schedule could positively support the requirements of Data Architecture.

A well-documented, management-approved retention schedule paves a path forward for Data Architects to exercise its governance requirements which include:

√ Govern and manage data as a strategic asset

√ Protect and secure data

√ Promote efficient use of data assets

√ Build a culture that values data as an asset

√ Honour stakeholder input and

√ Leverage partners

The audience was clearly salivating for more rapid-fire value statements. The presentation pressed forward in response!

Here’s where a retention schedule can deliver quick hits for Data Architecture:

Authorize redundant data destruction:

√ VALUE: Eliminate the damage voluminous outdated data can cause to a system’s performance.

Increase system performance:

√ VALUE: Capture business decisions to permit off-load of outdated data to less costly storage solutions.

√ VALUE: Retain frequently accessed data on-line or near-line.

Separate wheat from the chaff:

√ VALUE: Not all data is created equally; some require stringent business rules and resources.

√ VALUE: Understand when data has been assembled into documents of evidence,

√ VALUE: Documents can be relocated into an RM-DM system to live out retention requirements.

After these hard-hitting facts were delivered, the presentation reduced its pace to a conversational conclusion, explaining how:

- These illustrations of how a retention schedule can inform Data Architecture practices rely on populating the retention schedule with salient data about the data. The retention schedule is organic. As descriptive information is added, it becomes a dynamic operating tool that positions a Company to leverage its data assets for future opportunities.

- The action of aggregating data governance rules into a retention schedule will position a Company to understand the value of enterprise-wide data governance. Even elementary actions as defining data into buckets such as program data, statistical data, and mission support data will help a Company assign appropriate value and resources to its data.

The presentation concluded with a rousing statement:

“In short, a retention schedule is a dynamic operating tool that positions a company to leverage its data assets for future opportunities.”

Tip – Be Prepared for a Perfect Pitch

Records Managers have often been advised to prepare an ‘elevator speech’ – a 30 second sound bite which describes the records role in a business setting. One would employ this speech should an opportunity arise, such as shoulder to shoulder with someone in an elevator.

Philip Crosby, author of The Art of Getting Your Own Sweet Way (1972) and Quality Is Still Free (1996) suggested individuals should have a pre-prepared speech that can deliver information regarding themselves or a quality that they can provide within a short period of time, namely the amount of time of an elevator ride for if an individual finds themselves on an elevator with a prominent figure. Essentially, an elevator pitch is meant to allow an individual to pitch themselves or an idea to a person who is high up in a company, with very limited time.

There are many pitches one can prepare for, such as one’s current position and value-statement. For the purpose of interacting with Data Architects, or any IT discipline, a method of preparation could be by imagining a RIM role within an IT discipline – that is, by using business language common to both.

Some IT practitioners use the terms ‘Records Management’ and ‘Document Management’ interchangeably. The following excerpt from a recruitment notice uses solely ‘document management’. Since it refers to ‘company-wide … framework’, records managers would astutely point out the correct term would be ‘records management’; however, does the distinction matter at this level of conversation?

Remain focused on the big goal – continuous dialogue with other information management professionals to ensure records management principles are applied as “a consistently applied process for managing and controlling documentation”.

The following position description contains exciting language to memorize for an elevator speech. It has passion, potential and agile descriptions of how records managers contribute to the overall management of information resources. Here is a list of the position’s responsibilities:

- Work with business stakeholders, IT management team, Architecture and Portfolio Managers to further the objectives of overall information management practice;

- Assist the business, IT management team and Architecture team in developing, communicating and promoting key information management principles, standards and practices that govern the current state, and define the future state of IT;

- Work with Business and IT stakeholders to build a holistic view of the corporation’s information assets, and documents this using multiple views that show how the current and future needs of an organization will be met in an efficient, sustainable, agile, and adaptable manner;

- Help IT teams gather information management needs and demand in a structured manner and translating that demand into IT roadmaps;

- Promote and participate in sessions with business stakeholders and IT team to ensure policies are supported by the information management framework and standards while identifying the need for establishing new standards and practices.

In Conclusion…

What seemingly started quite informally, an invitation to present ‘what is a retention schedule to an audience of Data Architects, led to a reflection on being prepared to deliver a perfect pitch. Constraints such as verbal only — no supporting visuals; no ‘take away’ posting of presentation materials for the audience; and limited time are common to all situations – for example, an elevator!

To present verbally on a topic reasonably unfamiliar to an audience requires not only solid knowledge of subject matter, but also a colloquial delivery style which establishes rapport and confidence. To distill the components of a retention schedule into auditory consumable “bytes” is a challenge. Finding common ground among mutual information management-based disciplines seemed a positive path forward.

Are records managers prepared, on the spot, to convey principles in a sound-bite manner? As business language evolves, the use of phrases such as “must have” have outlived their audience tolerance. Measures are good; however, speaking about saving terabytes of space, or applying retention destruction to gazillions of documents is equally unmemorable.

A recent ARMA Calgary workshop focused on policy writing. What could be new? The examination of the language used in current policies was deemed ‘in the past’. Newer language states facts in simple, assertive statements such as “We protect records.”

Through research, presentations, and writing, records managers assert their future by embracing continuous education, change, and challenge.

Our Phygital World and Information Management:A human-centric approach, September 2019

Giles Crouch, design anthropologist, E K S P A N S I V, a design anthropology firm ©2019 Giles Crouch

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes, 5 seconds. Contains 6018 words

Introduction

To say that managing information in today’s increasingly complex world is a challenge would be an understatement. Information technologies have advanced so rapidly and become so deeply embedded in our daily personal and work lives that we can now say we live in what we can truly call a “phygital” world; the blending of physical and digital. Often, on the devices we use, from smartphones, laptops, tablets, watches and voice-controlled devices; the line between personal and work information is increasingly blurred and intermingled. For those in information and records management, this is not new. But new approaches and ways of thinking about information and communications technologies are needed.

These advances in technology have had and are having, a profound impact on workplace cultures and processes as well as society on an organisational and global scale. Before the internet and our always-on, hyper-connected world the issues of understanding how humans interacted with Information Communications Technologies (ICT) in regards to managing information within the organisation, workplace culture and rituals wasn’t deeply considered, for the most part, beyond the surface. Now, these factors will play an increasingly vital role to the management of the organisation. Successful management of ICT and information within the organisation means a more human-centric approach. More than ever, software and hardware companies are taking a much more human-centric approach in the very design of the tools they make. An example is smartphone manufacturers such as Google and Apple who have designed their devices to capture peoples’ attention to use them more. Not many of us would use a smartphone today that had a black and white user interface.

In just the past decade we have seen the rise of the UX (User Experience) and UI (User Interface) designer taking a front seat in software development. The old software development approach of consult, build, release, and revise in long cycles is over, replaced by agile methodologies and constantly released iterations. This was especially so for software tools delivered in the browser, known as Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), but even Microsoft is now constantly delivering updates to desktop software rather than releasing entirely new versions every year or two.

My work as a design anthropologist is seeking to understand the intersection between technology, society, business and culture to help solve complex problems from a human-centred perspective. This paper takes a brief look at why a more human-centric approach to understanding and designing information use and ICT tools in the organisation has become critical.

Context. From the bronze axe to the smartphone.

For many of us in the technology world, we simply use the tools we have or are presented with at home or work. Two generations have grown up using computers and software, especially Microsoft Office and the Windows operating system. The current generation is growing up with touch interfaces on smartphones and tablets and a new one will grow up with voice activated devices. We often look at the problems and challenges of information management from a place of “now” and where we are. Understanding the context of ICT’s in society and the workplace will help frame why it is critical to understanding the role that culture, ritual and inclusivity take when maintaining, designing and implementing ICT’s and information management policies and procedures.

The Bronze Axe and Cave Drawings

Two key facets of humans are that we communicate to survive and that we use tools that enable us to employ the strategies we communicate to each other to survive. For thousands of years a worker had to know how to socialize and communicate with co-workers and use tools to stay employed, thus earning a salary and putting a roof over their head and food on the table. How we communicate has evolved significantly as have the tools we use to survive.

As humans evolved, we developed language to communicate and we learned how to manipulate information. Along the way, we started to draw images on cave walls; the cave walls were dry and thus images lasted, and it was a relatively safe place where a lion was less likely to make dinner out of you and your tribe. We went on to create multiple complex languages and writing. Symbols became an important part of how we communicate. Symbols are evolving still, such as emoji’s; love them or hate them.

At some point we also developed tools – first spears and later knives, swords and other tools. The bronze axe played a very large role in human societies that could make them. It was the first time in human history we could build complicated things. The bronze axe is akin to today’s smartphone. The axe, like the smartphone, was a social signal. If you had a bronze axe as opposed to Axe Version 1.0 which was a cheap stone that chipped, it meant you were either wealthy or strong/clever enough to take it from someone else. Either way, you had status and thus influence. It also meant you could make shelter faster and easier, catch your dinner and do other things that most likely kept you alive somewhat longer than the chap with Axe 1.0.

The rise of digital tools

A wee bit later we invented the printing press, then the radio and television. Now we have our smartphones with TV show access and podcasts. Some suggest that with the vastness of today’s information, we have become overloaded with information. Arguably, we achieved information overload when we printed more books than a human could read in a lifetime. Humans invented libraries and archives to store and manage information. Before that, we used stone and wood. In a sense, a library was humanity’s first database. Just in analog format. Over time, the ability to read and write and communicate with broader audiences became both a status symbol and necessary for societal and species survival.

ICT’s are tools that integrate our ability to communicate and organise more deeply than ever before. A key aspect of ICT’s is that they reduce friction (friction arises in communicating when more steps are needed to communicate information; it is less friction to send an email than a mailed letter) and the ability to organise. Software and hardware are simply the bronze axe and papyrus reed of long ago, slightly updated.

For a long time, communications methods were largely broadcast in nature; TV, radio, print, with little to no immediate feedback ability. Even for a time, the internet was a place we went to. To access the internet you needed to use a very defined device, a computer. You also needed a fair degree of skill to operate a computer, which at one time, we very functionally specific. They weren’t connected. Once computers became connected and the Personal Computer (PC) was invented, things started to change. But for a very long time, the internet remained a separate place. We often called it Cyberspace. It was a space, separated from the space that the real world occupied. Our physical and digital worlds were distinct in nature.

While early mainframes were (and are) expensive, so were early desktop PC’s and they took up a fair bit of table or desktop real-estate, had to be plugged in and connected to other computers by cables. A certain degree of education was also required to interact with these earlier devices. Even laptops until recently, still required a physical connection to the internet and to access other computers or peripherals such as printers and a mouse. Most information technologies were, essentially, a fixed artefact.

In homes, special locations were set aside for computers; a spot in the kitchen or a special desk in a study or living room. Rituals evolved around when we would spend time on the internet, the software we would use and how the computer was treated, especially in family settings. For organisations, the initial PC investments were expensive, but IT had control over what software was available and when, so ICTs were more easily managed.

We understand today, looking back, that the internet as a tool, has had a profound impact on human society and how we communicate with each other, both good and bad. All technologies, or tools, have, throughout history, been good and bad. A bronze axe helped you make shelter and dinner, but it could also be used as a weapon to be nasty to other humans. While we see great benefits in Artificial Intelligence (AI), we also recognize that it can be weaponized by rogue states or generally bad people who want to do bad things.

Now, our world is hyper-connected, always on; phygital. Today, there are more devices connected to the internet than there are people in the world. Increasingly, technologies are becoming more assistive and invisible yet ever more pervasive. In most everything we do today, some form of information technology plays a role, sometimes without us realizing it is happening. As NYU professor and author of the book, Here comes everybody, Clay Shirky has stated, “When technology becomes invisible is when it gets interesting.”

No longer can we separate ICT’s from our work and personal worlds or our daily lives in general. Connectivity is everywhere and always on. This is why, as information management professionals, it is increasingly important to understand ICT’s as tools and see them from a more human-centric angle, not just as productivity tools. For so long, ICT’s were viewed as tools to manage information within the systems that they were designed to support. External connections were rare and they were not often designed to play with other tools.

The very language we have used in developing these tools is abstract and dissociative from humans. The ICT tool (software and hardware) was at the forefront, the human as a “user” and the user conforms to the intent of the tool and the business system it is being designed to work in. This, in essence, is placing function before form. The problem with all tools throughout human history however, is humans. When something goes wrong with a software tool we are using, we blame the human. We can also blame the human that figured out a bronze axe could also be used to thump some poor chap over the head. Someone always tends to do something with a tool that the creator never intended, such as forgetting to plug it in. Additionally, all technologies have a duality. They can be used for good and bad. Add in the human propensity to do the unexpected and we introduce the law of unintended consequences. When social media tools hit the world, the expectation was for democracy to sweep the world and life to be wonderful. Instead, democracies have shrunk and we have a new meaning for trolls and new words such cyberbully and hacker. On the upside, movements like #MeToo were enabled. We’re a quirky bunch.

An excellent example of this in an information management context is Dropbox. A brilliant concept as a tool to enable people to easily share files. Humans love to share information as we know. It’s how we survive. That was Dropbox’s intent and it worked very well. There were also a lot of knowledge workers who had better computers at home than at work (this is still very often the case) so they’d upload the file to their Dropbox account to work on at home or their personal laptop at a coffee shop. Before that, it was USB sticks. But services such as Dropbox, Google Drive and Box have led to a bit of a nightmare for information management.

Policies were put in place, sometimes they worked. Some organisations simply adopted Dropbox as their primary document management system. Some a hybrid of on-premise and Cloud solutions.

Humans will always find ways to work around organisational policies and rules as well. One rather significant example is the U.S. Marines in Iraq and the battle of Falujah during the Gulf War. The command officers came up with a battle plan, giving the orders on what weapons and tactics to use, all of which was communicated over the Army’s secure networks. The line soldiers who would be fighting the actual battle, however, had other ideas. They’d established their own secure network over top of the command one. They also determined they’d use slightly different tactics and which were communicated on their own network. They won the battle and likely would not have had they abided by the command network.

All of this is to say, the domain of creating, managing and operating ICT tools today is no longer exclusive to the IT department and those responsible for information management. In many organisations, we see departments using SaaS based tools they access via the internet without ever telling the IT department. In one recent technology audit of a firm who thought they were spending about $40,000 a year on various SaaS and related services, we found they were actually spending $320,000. It is a well managed firm with a strong IT department and firm policies and procedures in place. Yet this still happened and happens often.

Because ICT tools are increasingly easier to use and technology is so pervasive in both our personal and work lives, those in IT and information management will have to take a more human-centric approach to governance, management and deployment in the coming years. Next we explore the cultural, ritual and inclusivity aspects of our phygital world.

Understanding culture with information technologie

Technology, information and culture

As computers and PC’s began to enter organisations in a meaningful way in the late 1980’s, they were mostly for very defined activities; word processing and accounting. Finding a senior executive who had a PC monitor on their desk was a rare sight indeed. At that time, computers were simply seen as a tool used by line workers, not those with seniority. They held little social currency and were not seen as a signal of power. Into the 1990’s, as computers became networked, easier to use and purchasing costs lowered, they crept into more and more roles within the organisation.

Companies like Microsoft and Apple updated their operating systems from command lines to using Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs).) Rather than having to know code, one had to learn how to interpret symbols. In lock-step with PC’s came connected photocopiers that copied and printed from computers. Monitors became colour as well. The cost of networking became less, but required significant infrastructure investments such as ethernet cabling and networking equipment. Then, with networking advances came the internet. Once the cost of computers started to come down and the internet evolved to connect consumers, things really started to shift. PC’s began to gain social status both at home and at work. Laptop PC’s started to become cheaper as well. The cost to create information became much lower as did the friction.

Where previously, from the late 70’s to the late 90’s it was secretaries and other administrative staff who had to know how to use a computer, by the late 90’s sales people and even middle-level management also had to know how to use a PC. For sales people, the laptop became a primary working tool. The black leather or nylon laptop bag became ubiquitous at airports and on subways. This was also a boon for physiotherapists for all those workers with shoulder and neck problems from lugging heavy laptops around. Now, senior executives wanted a computer on their desk. The PC had become a status symbol at work. This is also, arguably, when we lost the work/life balance.

What type of device you had often indicated your seniority within an organisation for it indicated how much information you had access to. Seeing a large monitor on an executive’s desk implied they knew how to use technology and that they had access to and control over, important information. If you used a laptop, it conveyed that you were someone who was mobile and worked more outside the organisation’s walls. It suggested importance. The computer had now begun to establish itself in the organisational culture.

It was also around this time, the early 00’s that cell phones became more ubiquitous. Smaller, lower cost to operate and a key business tool. But until the launch of the Blackberry and then the iPhone in 2007 cell phones were more of a business tool than a consumer device. Having a Blackberry prior to the iPhone sent an even bigger signal of social importance within the organisation. When the iPhone launched, it put the device into the hands of the consumer. PC’s became far cheaper as processing power, memory and displays dropped significantly in cost. Then of course, came tablets, the Cloud and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) companies exploded.

This is also when email become very popular; a tool that still hasn’t been replaced. It is also another example of us quirky humans. While it was intended as a work productivity tool, humans found email to be an excellent way to share jokes leading to many embarrassing incidences of people hitting “reply all” by accident and office romances were unhappily discovered. To this day, email etiquette remains a hot topic in the workplace.

The combination of lower cost PC’s, ubiquitous and high-speed internet (and Wifi), smartphones, tablets, the Cloud and social media have had a profound effect on corporate cultures. The latest devices to impact the workplace are the smartwatch and fitness trackers. Again, owning an Apple Watch sends a signal of status versus a simple FitBit fitness tracker. While few organisations see the value in a smartwatch for employees, they still connect to corporate smartphones and networks and send a signal of a person’s income level.

The advances of ICT tools have led to increased collaboration between departments and across different organisations. This has also resulted in friction between younger and older workers in an organisation. Many of those who are in their mid-40’s and above, are used to an information environment that had more silos and departments that rarely shared amongst each other. Information is power.

The power dynamics of information

The power dynamic of information within the organization is important to understand. Senior executives are seen to have access to any and all information. Access wanes as the roles perceived importance declines. This also plays into inclusivity, which we discuss later. For those in information management, understanding the dynamics of power in regards to ICT’s and information is a key part of forming policies and developing or employing new tools in the organisation.

ICT operations have developed from a largely administrative role with minimal social and cultural status within an organisation, to playing a key role culturally. Along with devices, information access and what tools you use to create, manipulate and manage information have also come to hold cultural significance. For instance, consider the communications tool, Slack. It is supposed to be a productivity tool that enables teams to collaborate far easier and to some degree it does. Slack’s creators seemed to think it would eliminate email, but not so far. While it is an excellent tool, Slack has added yet another layer to the complexity of information management today, most specifically in the area of document management. Slack enables communication outside of the organisation, thus creating an added area of cybersecurity worries for IT departments and those trying to manage information. Slack has also evolved its own culture within organisations, as have other tools.

Another often overlooked or missed power dynamic in the workplace is the “Fixer” as we will call them. This is the one person (and there may be one or two in various functional units) who know a particular app or database extremely well. They’re the resident expert and they fix peoples’ problems. This provides them with a degree of power within organisational culture. Changes to such tools, or the introduction of new ones, change this person’s power dynamic. They may be highly resistant to new tools because of this. Often Fixers feel that because they know these tools so well, they are more valuable to the organisation and have a greater degree of job safety. Fixers can be major roadblocks or they can be turned into champions. When they are recognised and made a key part of a transition, selection or policy development team, Fixers may be a significant benefit to a project’s success.

As mentioned, many organisations are often unaware of how many tools like Slack are being used. When an employee in one department is invited to collaborate with another department, they may end up using a tool that the other department uses. This may lead to a feeling of being included in a special way, which has an impact on the organisational culture. And inclusivity, which we address later.

Understanding the cultural impacts of ICT within an organisation, may lead to deeper insights regarding how people create, manage and share information. Such insights assist in creating better policies and procedures. Often, policies are ignored or worked around because they don’t align with organisational culture. Employees may feel alienated by some policies or tools and others may feel that the policies hinder workflow and reduce efficiencies. Culture can have a significant impact when considering major projects such as digital transformation or selecting and implementing new database or software tools.

Understanding the role of ritual with information technologies

When we hear the word “ritual” we tend to think of religious ceremonies and while it can be a version of ritual, it isn’t the definition of ritual. Think of your own morning routine when preparing for work, it is a form of ritual. Perhaps first you put on the kettle for tea or brew a coffee, feed your pets and begin getting ready for work during the work week. On the weekend, you may have a different routine. These are rituals.

People have similar rituals with their devices, from smartphones and tablets to their PC. From where we set up the device in our workspace and how we begin our day, to how we arrange apps on our smartphones and tablets. Perhaps checking email, which we often do on a smartphone before we even get to work. With the different software apps we use, we often have a ritual in the way that we use them as well as other productivity tools. Chances are you have a desktop wallpaper on all your screens and you’ve customized the apps as much as you can to your preferences. Changing these ritualistic behaviours can make us angry and frustrated. Part of the reason we don’t like changes in apps is because it interferes with our rituals. To a large degree these rituals play a part in our workflows.

Rituals also take place due to the volume of information created and stored. A new app or perhaps a change in the SharePoint structure or an SAP tool means a change in how an individual finds and manages information; this means a change in ritual. The bigger the change, may lead to e more resistance to the change, such as we’ve discussed with Fixers. Ritual is important to the individual worker and helps in understanding issues of inclusivity and culture, but play a lesser overall role. But are still valuable to acknowledge and understand.

Inclusivity in a Phygital Organisation

Tied to organisational culture is inclusivity. Information technologies have no opinions and are agnostic. How they are deployed within an organisation however, can impact employees’ sense of inclusivity. For example, management handing down their laptops to lower functioning roles could lead to a sense of people not feeling included as part of the organisation, or as less important. Even colours used in applications can impact some cultures. A heavy usage of yellow for example, may make some of Indian culture think of funerals as yellow is a colour representing death in India as blue is in Chinese culture. Expectations regarding the use of the organization’s information technologies may impact how employees feel included in the organisation. For example, the expectations on the use of an organization’s technology on weekends; are there expectations to answer emails on a Saturday or Sunday, when some employees, for religious reasons believe they should not be using these devices..

One example of inclusivity that may seem trivial, yet had a huge impact on how employees’ saw themselves within an organisation, was in regard to email addresses. In this example, senior management had an email address that represented the parent brand, while employees and lower management had email addresses for different brands. The employees feel undervalued and not part of the main brand they felt more empowered by. This caused ongoing friction between employees and management. Management resisted making any change for a long time. Eventually, with the intervention of the CIO and HR executive, all employees were given the same email address. The impact on morale was profound in a positive way. Small things can lead to big things.

In any organisation where information technologies are a key part of an employee’s job performance, issues of culture, ritual and inclusivity will play a key role in how people perceive, accept and work with the tools they are provided.

For decades, the development and deployment of information technologies has been made from the perspective mostly of the developer of the tools and the requirements of the buyer. People have been seen simply as “users” rather than humans. As mentioned earlier, the word “user” is an abstract term that creates a sense of disassociation between the human designing the technology and the human that has to use it every day at work. The user has simply been viewed as a functional part of the system, yet it is the humans which cause the most problems with information technologies. And as we’ve touched on, humans are quirky and will do unexpected things with technology.

A more human-centred approach to information management, changes how software and hardware are designed, developed and deployed within an organisation. This is in part, the role of the U (User Experience) designer and the UI (User Interface) designer. To better understand the impact of human behaviours on software or an overall ICT system, more organisations are using the anthropological process of ethnography before and during the development of solutions, whether they be hardware or software. A certain tension always exists in how an information management person sees the best solution and the humans on the other end who use the tools.

Emerging trends in software and hardware

Earlier, we mentioned when technologies become invisible they become more interesting. This is starting to be the case with software. Hardware has become increasingly invisible (many people over the past 20 years have grown up using a computer and over the last decade, a smartphone) and somewhat plateaued in terms of capabilities. For decades hardware evolved significantly every year. This is known as Moore’s Law, where computing power doubles about every 18 months. Today, we are reaching the end of this evolution. We see minimal advances in storage, processing power and screen quality. This is very good for software and the humans who work with software.

For decades, there was a constant tension between software and the hardware it worked with. It led to high development costs and significant impacts on organisations ICT budgets and how they invested. With plateauing most PC’s and even smartphones and tablets, and the rise of Cloud computing, software now has an opportunity to become much, much better. And we see this with ever greater emphasis on a more human-centric approach to software development. Using what is called Agile Methodologies, software updates are more iterative and constantly improving whereas before it was all about strict version control and what was known as waterfall methodologies. In some cases, waterfall methods still apply, but are not as prevalent as they once were.

Increasingly, software tools are being developed from the outset to be more connected to other tools. This is done through Application Protocol Interfaces (API’s) to the point where some pundits refer to the “API Economy” where entire business models for software products and their very survival, are based on connecting to a major platform. Tools like Trello, Monday (visual project management), Dropbox and others work best when they connect to platforms such as Slack, Google’s GSuite or Microsoft Enterprise and Microsoft Azure.

Many years ago, platform companies like Apple and Microsoft made a point of not enabling their software to work on each other’s platforms. This is no longer the case. While in certain instances Apple, Google or Microsoft may not enable certain features? to play well with each other, they increasingly interconnect with each other. Microsoft Office and OneDrive for example, work across Apple OS’s and Android.

Many software and hardware companies are also leading development today from a human-centric design perspective. This is especially so with regard to IoT (Internet-of-Things) device makers who study human behaviours more than ever before. Software is about to get a lot better, but it is also going to be more complicated for organisations to implement and manage so many variables and layers. Sorry about that; humans are quirky that way.

A quick look ahead

While predicting the future is impossible, we can see to some degree, where information technologies are going. Some will have a significant impact on information and records management.

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The use of AI may be very helpful to information management, or it may not. AI could, for example, be used to monitor how information is managed within an organisation and recommend or make, changes. The risk is in attempting to fully automate this process which could result in more problems elsewhere within the structure of the organisation. AI will play a vital role in managing ever more complex systems that go beyond the human ability to comprehend.

Blockchain: This is a very promising technology, especially in records management. It will enable the stamping and confirmation of records in that they cannot be altered or tampered with, thus better guaranteeing contracts and document security. While blockchain offers key advantages, it is not a perfect system. For example, there is the 51% exploit whereby a hostile entity gains control of 51% or more of the power in the blockchain and can force the other participant systems to agree to a change, such as transferring funds to a fraudulent account.

Internet-of-Things (IoT): These are devices with sensors that connect to the internet. They can range from the common light bulb all the way up to complex manufacturing devices. The most well-known consumer IoT device is the Nest thermostat for the home. Some companies are developing IoT devices that fit in the toilet and will be able to monitor sugar levels and bacterial infections among other human maladies. A significant value of IoT devices isn’t the function they perform, rather it is the data they collect. IoT connected home devices can, for example, help power companies understand and manage energy loads on the grid.

Augmented and Virtual Reality: Still fairly expensive and a new technology, augmented reality (AR) is already being used in industrial settings with smart glasses that can overlay information and we are seeing it deployed in some smartphones and vehicles. Virtual Reality (VR) remains expensive in terms of the hardware and content development. Both AR and VR reside mostly in commercial applications and those being mostly industrial and military.

Autonomous vehicles, augmented and virtual reality, drones and biotechnology are all other tools that are emerging. They will add new layers of complexity for information management professionals. They will require new workplace and organisational policies and procedures and governance approaches.

Concluding

Our world is more complex and it’s not going to become any less complex, anytime soon. It is increasingly harder to draw the blurring line between information within and without the organisation, especially in terms of managing it. No doubt, better tools to accomplish this Herculean set of challenges will come along. Those that take a human-centric approach however, will have a greater chance of success.

For those in the field of information and records management, taking a more human-centred approach to understanding how and why information technologies are used within the organisation can be extremely helpful. By understanding power dynamics, one can see how information is viewed within the organisational structure, which can help in suggesting, recommending and defining new technologies, policies and procedures and governance. By understanding culture, it makes digital transformations easier and invites new ways of introducing not just new technologies, but gaining acceptance of new policies by employees. Looking at ritual helps with designing and deploying new policies, processes and tools to anticipate challenges and acceptance. And by taking inclusivity into account, this helps with messaging and policy planning as well as workplace morale and culture.

For decades, with the development of information technologies, the human was seen as being in the loop of the system, but they were seen as a functionary that would perform in predictable ways, and the tools themselves were designed for organisational systems that worked for the organisation internally. And as discussed previously, both software and hardware suffered from paying more attention to the humans using the tools and focused largely on the user. In the late 1970’s we saw the rise of the Human Computer Interface (HCI) practice, but as computers were larger, interfaces restricted (GUI’s were a dream at XEROX Parc).

Such a dissociative approach to developing information technologies is changing. Now we have Agile development Methodologies, rapid deployments, iterative processes. Data moves across organisational functions, resides within and without the organisation and is increasingly difficult to manage, secure and control. How people use the tools and consider information has evolved significantly over just the past decade. While the technologies have blended the result is that culture, ritual and inclusion play a more significant role in how humans perceive information and use information.

Information technologies are evolving rapidly and as we live in a phygital world, where devices and information creation and sharing accelerate, a human-centred approach to developing policies and new tools is key to successful development, implementation and management.

For this paper, I used my own laptop, keeping the document in the Cloud as I was working on it. Some of this I wrote in cafes, some at my desk, parts on my smartphone and some on the couch in the quiet of the evening. I also accessed documents in other organisations systems where I had permission to do so. In other words, though this is a single document, the information collected to bring it together, resided in many places with various rules and it was written in various locations across multiple devices.

Information technology and management is less about “users” today and more about humans as we evolve our understanding of how humans interact with technology at work and at home. It is increasingly hard to separate the two, especially with smartphones that may have both a corporate and personal credit card on them and mixed personal and work documents. Such a device may have music that is connected to the employee’s vehicle and home network where we increasingly see people with internet connected thermostats and other household appliances. It may also connect to IoT devices in the office and move various types of personal and work information.

All of this requires new approaches to how we consider and manage information within the organisational context. A design-oriented approach that is human-centric helps build a more contextual awareness in the development, planning and implementation of information management and ICT tools within the organisation. As we see more devices enter the organisation and as collaboration features become more prominent in almost every ICT tool and software application, new pressures on existing systems will occur and new challenges will emerge.

Employees can work almost anywhere. Information lives in multiple locations. Devices are becoming ever easier to use just as the software is becoming easier and ever more interconnected. Traditional approaches to information management and ICT tools are having to evolve. Complexity of systems and tools will increase. Artificial intelligence is creeping into ever more organisations just as analytics tools struggle to bring value. As we know, humans are quirky in how they see tools and use them in their everyday lives.

For thousands of years, information was largely static. Today, it has become fluid and ever shifting.

Preserving the Legacy of Residential Schooling Through a Rawlsian Framework

Alissa Droog, Dayna Yankovich, Laura Sedgwick – MLIS Graduates, Western University

Estimated reading time: 34 minutes, 48 seconds. Contains 6963 words

Introduction

Indigenous Peoples in Canada have been mistreated. A notable example of this mistreatment is the residential schooling system in which countless Indigenous students were unwillingly taken from their homes and forced to attend boarding schools where they were, in many cases, abused physically, sexually, or emotionally. In trying to make amends for what was done, the Canadian Government developed initiatives to help move towards truth and reconciliation. In moving forward, issues regarding handling important records emerged, specifically the Independent Assessment Process (IAP) records, relating to how survivors of residential schooling systems were treated. In 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that these records should be destroyed.

This paper evaluates this controversial decision through application of John Rawls’ Principles of Justice. Rawls is a 20th century American political philosopher whose Principles of Justice, namely the Principle of Equal Liberty and the Difference Principle, provide a framework to understand justice and fairness within society. More specifically, these principles assert that everyone ought to have equal rights and that where disparities do exist, social structures ought to benefit the least advantaged groups (Garrett). As Indigenous Peoples have been disempowered by Canadian society, Rawls’ Principles of Justice has been chosen as a lens to view this case as the focus on power imbalances effectively shines a light on themes including justice and fairness in a society of diverse groups and values. The exploration of Rawls in relation to this court case suggests that the decision to destroy these IAP records does not support the survivors or efforts for reconciliation. Furthermore, this is not how human rights cases ought to be handled as it does not benefit the least advantaged groups.

Research Question

How can the 2017 Supreme Court of Canada’s decision (Canada (Attorney General) v. Fontaine, [2017] 2 SCR 205, 2017 SCC 47 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/h6jgp>) regarding the destruction of Independent Assessment Process records be evaluated considering Rawls’ Principles of Justice?

Background

The residential schooling system lasted for over 150 years in Canada and was attended by over 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 3)(TRC). In many cases, children were forcibly removed from their parents to attend these boarding schools which were funded by the Canadian government and run by religious organizations. Many perished or were abused at the hands of their caretakers. Beginning in the 1990’s and 2000’s, survivors of abuse in residential schools began to take their cases to court and in 2007, the Canadian government established the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA). This agreement provided compensation to survivors of the residential schooling system, supported healing measures and commemorative activities, and established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) (“Indian Residential Schools”).

Compensation was provided to survivors of the residential schooling system in two ways. All attendees of the residential schooling system were entitled to receive compensation based on the number of years they attended through the Common Experience Payment (CEP), or, negotiate a different sum via the Independent Assessment Process (IAP). Over 79,000 survivors who came forward to receive the standard $10,000.00 for proof of having attended the schools, and an additional $3,000.00 for every additional year they attended (Logan 93). The IAP allowed survivors to receive additional compensation to the CEP if they suffered lasting psychological harm due to physical, verbal or mental abuse experienced in the schools. IAP applications were received between 2008-2012 and 38,257 claims have been received through the IAP process to date (“Indian Residential Schools”).

In 2008, the IRSSA also established the TRC which had two goals: “reveal to Canadians the complex truth about the history and the ongoing legacy of the church-run residential schools…” and to “guide and inspire a process of truth and healing, leading toward reconciliation…” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 23). Between 2008 and 2015, the TRC travelled across Canada collecting documents and 6,750 statements about residential schools (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 29). The TRC encountered several obstacles in gathering documents about residential schools, including resistance from the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), Library and Archives Canada (LAC), and difficulty gaining records from the IAP held by the Indian Residential Schools Adjudication Secretariat (IRSAS). The TRC won court cases with LAC and the OPP to turn over records relating to residential schools, but the debate over who should house the IAP records has been fraught with ongoing tension (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 27-28).

The tension between privacy and sharing records of trauma shown in the IAP court case reveals a complex story about reconciliation, privacy and record-keeping in Canada. In 2010, the TRC and IRSSA created a consent form allowing anyone who shared their testimony through the IAP to have their records and testimony archived with the TRC; however, this consent form did not exist at the time that the IAP started and survivors often failed to understand the difference between the TRC and IAP (Logan 94). To complicate matters further, the IRSSA “required an undertaking of strict confidentiality of all parties to the IAP hearings, including the Survivors themselves” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 28). In 2014, the Chief Adjudicator of the IAP supported a decision that all records from the IAP process would be destroyed immediately (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 28). In the court case which followed, the TRC sought to archive the IAP documents with the LAC “as an irreplaceable historical record of the Indian Residential School experience” (Fontaine v. Canada (Attorney General), 2014 ONSC 4585 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/g8hd3>).

The court ruled that unless the claimant came forward and chose to share their documents with the TRC, IAP records would be destroyed after a 15- year retention period. This decision was appealed in the Ontario Court of Justice in 2016, and then appealed again in the Supreme Court of Canada in 2017. In both cases, the decision by Justice Parnell was upheld and, unless future action takes place, these records will be destroyed by 2027 (Indian Residential Schools Adjudication Secretariat).

Literature Review

A review of the literature reveals a body of scholarship dedicated to shedding light on the importance of record retention after an atrocity takes place. Record collection and preservation after human rights abuses are important steps in the healing and memory keeping process. However, the archives could become a contentious space when various groups lobby for their own best interest and seek to obscure the collective memory to their own advantage. The work of reconciliation or restorative justice relies on accurate assessments of the past and the creation of archives play an important role in either advancing or detracting from this work (Logan 92).

Truth-telling as a path to healing remains a widely held consensus among post-conflict scholars, however, Mendeloff challenges these claims as based more on faith than on empirical evidence of peacebuilding (355). The notion that truth-telling fosters reconciliation, promotes healing, deters future recurrence, and prevents historical distortion appear true anecdotally, even if scientifically unverifiable (Mendeloff 356). To this end, TRCs have become a common mechanism of post-conflict restorative justice work.

These commissions aim to reconstruct and repair the fractured social fabric within a conflicted society. Over the past 25 years, TRCs have been commonly employed post-conflict, typically following a similar pattern of providing all sides an opportunity to testify to their own experiences. The accounts are then collated into a unifying history of the human rights abuse, with a goal of recovery, as truth is unearthed, and societal memory is established. Over the past 25 years, TRCs have taken place in South Africa, Sierra Leone, Peru, Timor-Leste, Morocco, Liberia, Canada, and Australia, with many more planned for the future (Androff 1964). TRCs typically have little connection with the court system, and in instances where they do, it is in the interest of persecuting offenders. The South African TCR referred perpetrators to the court system, while Sierra Leone determined beforehand that serious crimes would proceed through the United Nations (UN) and lesser offenses through the TRC (Androff 1969). When the courts are involved, it is to work on behalf of the victims. Regardless of the court involvement, TRCs are designed “to produce a coherent, complex, historical narrative about the trauma of the violence and provide victims with the opportunity to participate in the process of post-conflict reconstruction” (Androff 1975).

Wood et al considered the field of archival studies and provided a critique of current practices in support of human rights work (398). They argue for a more nuanced look at the established archival description techniques and ask how it would look to invest less power in the institution housing the records and more in the people involved. The archival concept of provenance, that is ownership or custody of the record, becomes problematic when considering human rights records which hold community value. Citing an example from records of Indigenous Australians, Wood et al. discuss the use of parallel provenance and a participant driven model that honours the individuals and communities involved in their creation (403). These authors go so far as to describe an iterative recordkeeping process, where records are not static but include the voices of those who preserve, teach, add to, or in any other way become a part of the life of the record (Wood, et. al. 403). This honours the record as alive and relevant to the life of the community.

When the Supreme Court reached its decision regarding the destruction of the IAP records in 2017, the case received significant national news coverage. Headlines from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) included “Court order to destroy residential school accounts ‘a win for abusers’: [National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation] NCTR director” (Morin), and “Indigenous residential school records can be destroyed, Supreme Court rules” (Harris). Then again in 2019, the case received attention with the development of the My Records, My Choice website, created by IRSAS, which provided the option for record preservation. CBC reported, “New website helps residential school survivors preserve or destroy records” and Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) National News featured the article “Former TRC chair encourages residential school survivors to save records” (Martens).

The IAP itself has been studied and Moran provides a thorough legal review of the IRSSA, which includes a multiple page summary of the IAP (Moran 531 – 564). This legal primer sheds light on the nature of the IAP, specifically its design as a high-volume litigative process, with some features curtailed to keep the proceedings claimant-centred. For instance, “perpetrators are not parties and [that] they have ‘no right of confrontation’ during the hearing. The limited rights of alleged perpetrators were expressly designed to protect that safety and security of the claimant during the stressful hearing process” (Moran 561).

Similarly, Morrissette and Goodwill provide a detailed overview of the IAP process but from a health and human services perspective (542). Coming from this lens, they speak to the therapeutic relationship of survivor to therapists, and the unique healing requirements that may come about as a result of this process. These authors consider the rationale that led people to submit themselves to what may result in further traumatization: “For some survivors, formal hearings provide an opportunity to finally reveal the truth, describe their experiences, and assist in the prevention of future similar human tragedies and cultural trauma” (Morrissette and Goodwill 555). When a person opens up and expresses their experiences, this can prevent what these authors call a conspiracy of silence surrounding trauma, because “silence is profoundly destructive and can prevent a constructive response from victims, their families, society, and a nation” (Morrissette and Goodwill 555). Reimer has written a lengthy qualitative report on the experiences of those who participated in the CEP process. Although written before the start of the IAP, she asked participants about their thoughts on both the CEP and the proposed IAP. Many reported instances of re-traumatization as a result of participation in the CEP. Some stated the large amount of paperwork and involvement with lawyers was a deterrent for participation in the IAP (Reimer xiii-xvi). This was written before the official court decision regarding the destruction of the IAP records. Further research is needed to investigate how this decision will impact the healing and reconciliation process. Will this undermine the important work of traumatic disclosure and thus re-victimize participants? A gap exists in the literature. It is important to revisit this issue with consideration of legal, ethical, archival, and human services perspectives as aforementioned works do not sufficiently address these concerns. Previously mentioned works describing the IAP do not realize the future destruction of the records. As such, it will be important to revisit this issue both from a legal, ethical, archival, and health and human services perspective.

Methods

To answer the research question, a literature review was conducted to determine existing gaps surrounding the NCTR, IRSSA and the IAP. Relevant documentation and literature were identified, reviewed, and analyzed. Much of the important information required for this research came from the IRSSA website. This website provides a range of information pertinent to this inquiry ranging from the IAP application guide to My Records, My Choice options to court decisions and legal documents and more. Rawls’ Principles of Justice framework was then applied to assess and analyze the documentation and final court decision. A series of secondary questions were developed and considered to further motivate the process and answer the research question.

What happened?

It is important to understand the background that led to the court decision regarding the destruction of IAP records before trying to evaluate the ethical dimensions of this case against Rawls’ Principles of Justice. Background knowledge of the situation can help to provide context for how people were treated and the decisions that were made to move the case forward. Furthermore, this additional insight helps to provide information from diverse perspectives held by various stakeholders. Such insights contribute to building a full image of what happened and who was affected. This is necessary to enable assessment and evaluation against Rawls’ Principles of Justice.

What arguments led to court decision?

Court documentation reveals a variety of conflicting arguments and considerations that led to the final decision to have the IAP records destroyed in 2027. Arguments in favour of destroying the IAP records include: promoting the autonomy of survivors (as they have a choice whether to reclaim and preserve their own record or let them be destroyed) and maintaining confidentiality (as survivors were told their records would be destroyed, according to one judge’s perspective). Arguments opposed to destroying the records include: the importance of preserving this information for future generations as a record of the atrocities that Indigenous people experienced throughout the 19th and 20th centuries contradictory evidence that could indicate that IAP records could be archived. A point of contention in the case was whether or not the language shared with the IAP claimants indicated that the records would be archived or destroyed after use. Various judges had differing perspectives on this matter. Further, the courts took into account whether the records ought to be considered government records or court records as government records are subject to “federal privacy, access to information, and archiving legislation” (Canada (Attorney General) v. Fontaine, [2017] 2 SCR 205, 2017 SCC 47 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/h6jgp>). This consideration is more pertinent to legal rather than ethical dimensions of the case.

What biases and values need to be considered?

Biases and values that ought to be considered when addressing this research question include those related to which groups are in power, the diversity of values and perspectives, as well as personal biases.

This analysis focuses on the 2017 court case and how to move forward with the IAP records rather than the initial intention behind this process. Limitations of this research include lack of access to diverse perspectives and the inability to consult the various stakeholders to learn their views. Were we able to survey the survivors we would have a better sense of their values and desires moving forward. Further, we could better consider the relevance of diverse perspectives to Rawls’ Principles of Justice. In part due to these limitations, this is an exploration of Rawls in relation to the court proceedings and not a definitive decision on how the case ought to proceed.

Theoretical Framework

Rawls’ Principles of Justice are concerned with the ways in which rational persons would structure a society if they were a behind a so-called “veil of ignorance” that distorts any knowledge about who they are in the world.