Metadata in Recent Canadian Case Law

By Joy Rowe

1.0 Introduction

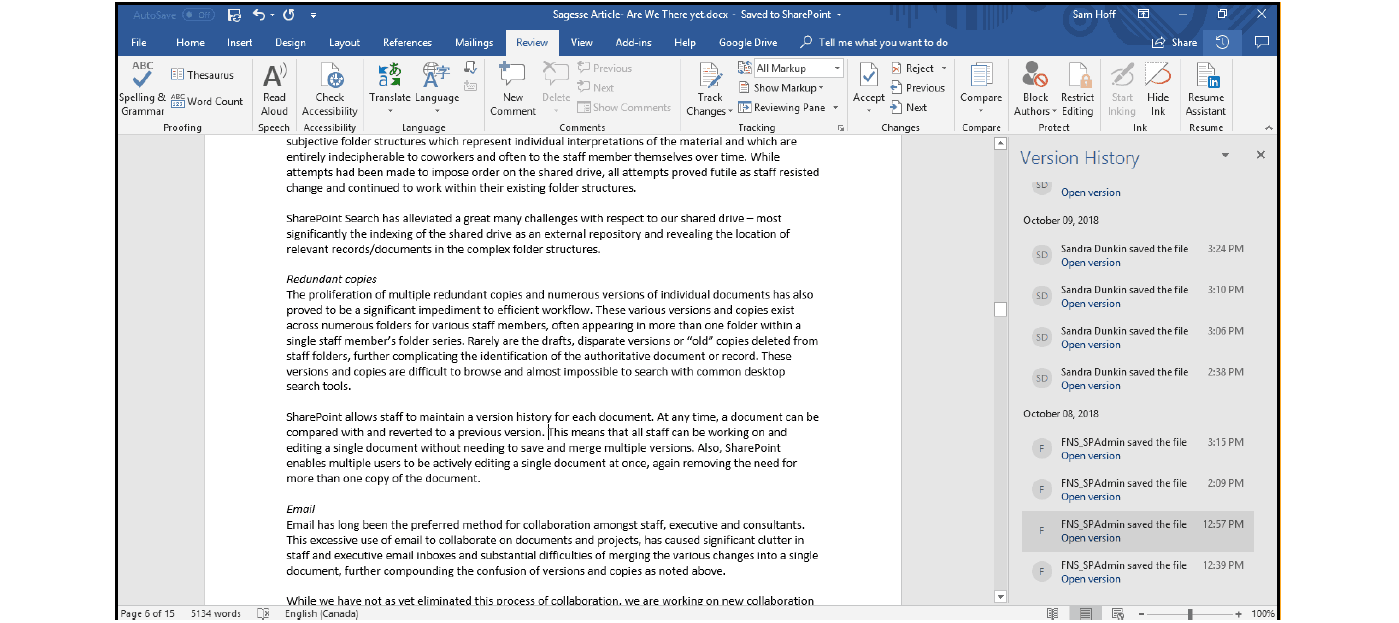

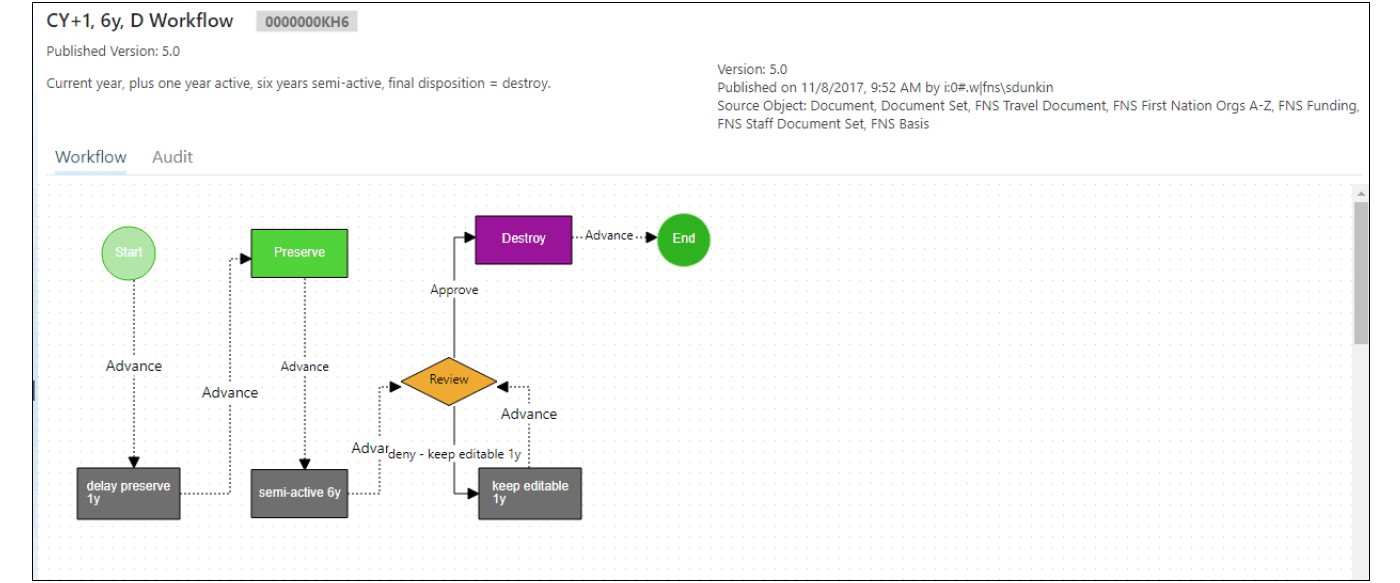

Metadata underlies every part of modern records management, from the digital records captured in an electronic document and records management system (EDRMS), stored in shared drives to the automatic logs being constantly generated by the computer system. The filename entered before saving a new document, the date and time that reflects the last instance the document was opened, the formulas and scripts linking together different portions of a document such as notes, bibliography and text and the countless “prior edits” automatically registered as this article was being prepared are all part of the hundreds of pieces of metadata that are associated with a typical digital record. Metadata reflects both the traces of human interactions with electronic systems as well as the trails of countless automated computer activities that require no human intervention. As a ubiquitous part of the digital realm, metadata is a key element of the records and information we manage.1

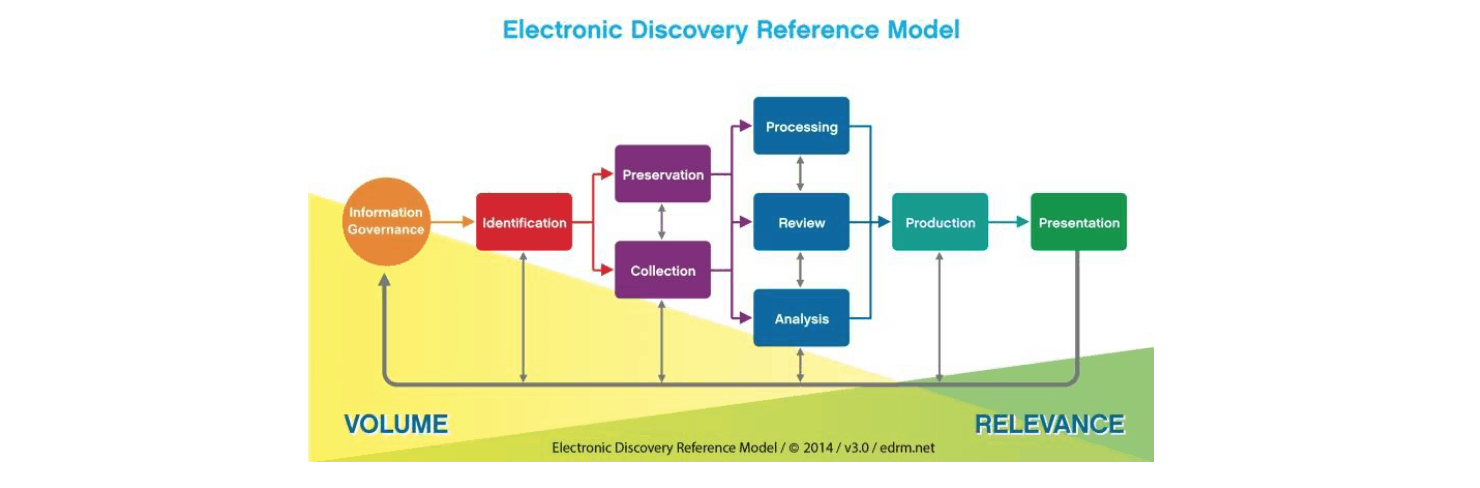

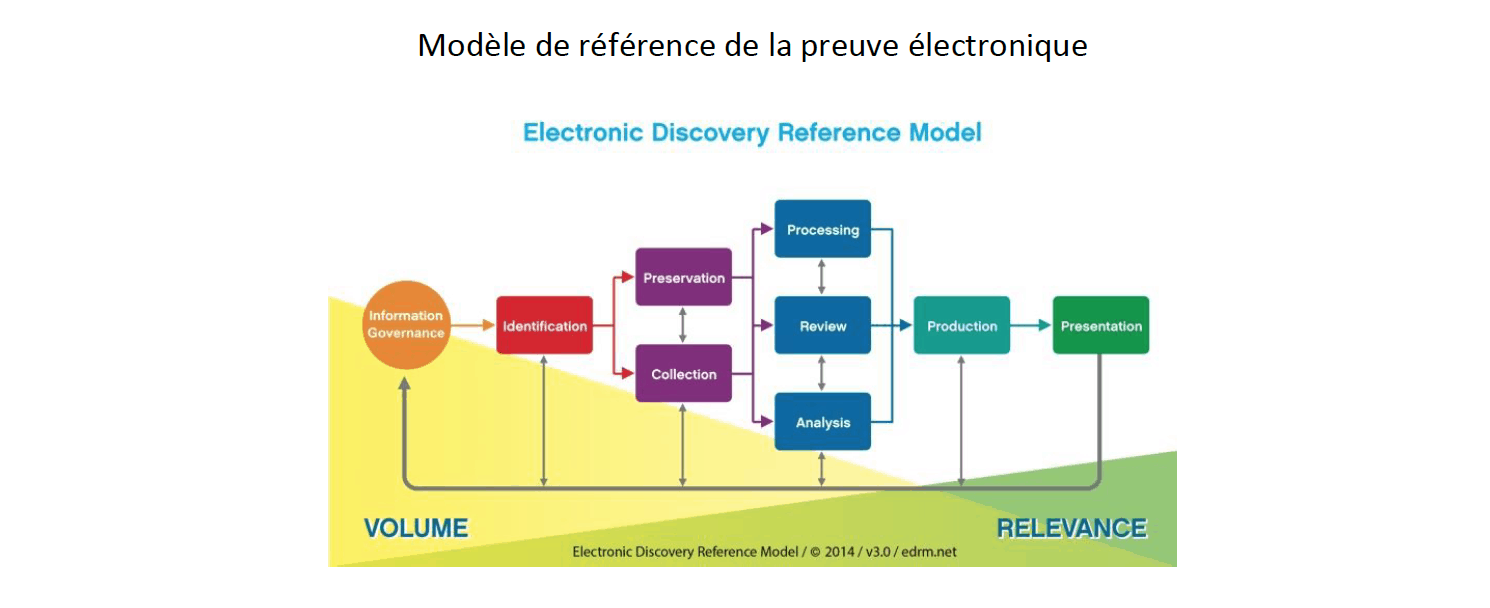

Archivists, concerned with the permanent retention of select digital records, have explored the roles of metadata in the multiple tasks of preservation2. Records managers, involved in the creation and numerous business uses of digital records, have focused on the role of metadata for retrieval functions3. Both professions within the information management field have also considered metadata as part of the legal uses of records. This includes the importance of good metadata for timely, accurate identification of records to facilitate the retrieval of records during the legal discovery and document production processes. It also includes exploring the legal understandings of authentication and integrity of the digital recordkeeping system4.

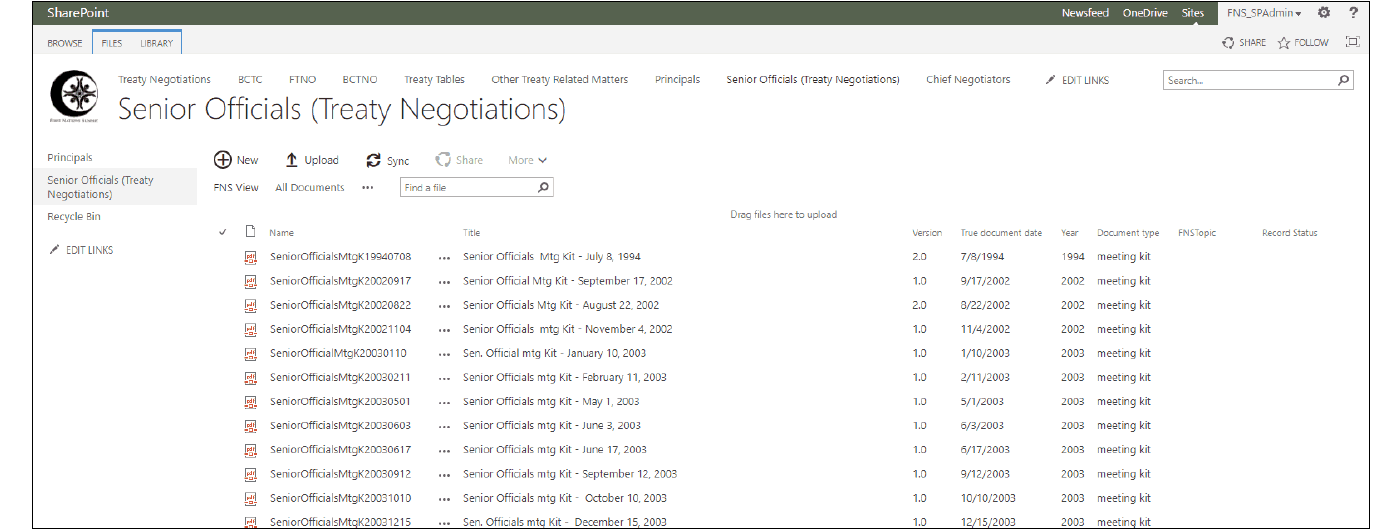

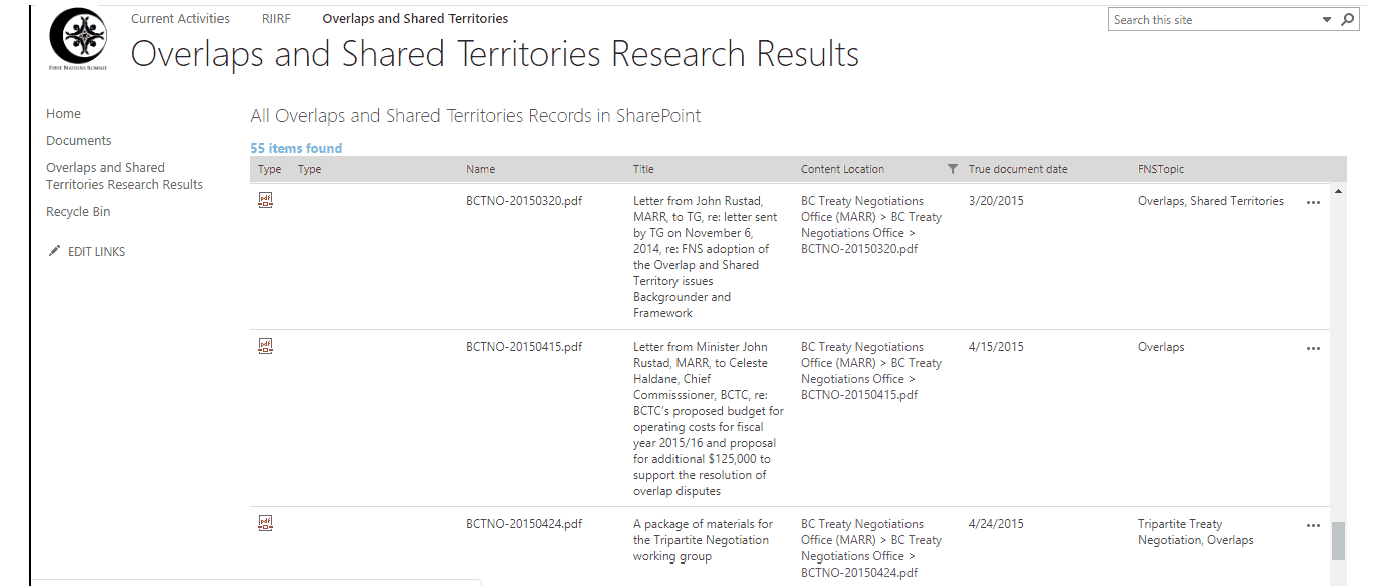

Many discussions of metadata in the legal context tend to center around the discovery process. This article looks at metadata in the Canadian legal context with a focus on admissibility5. Its purpose is to guide records and information professionals in the multiple metadata tasks undertaken in the course of their work where the legal uses of records and information need to be considered. These may include, but are not limited to:

- establishing meaningful and useful metadata profile in electronic document or record systems;

- communicating important legal distinctions of digital information creation methods to IT or other colleagues, and;

- using basic metadata type classification to correctly characterize electronic information as potential legal evidence for admissibility

Drawing largely from recent case law rulings, this article examines how metadata is treated as electronic evidence in the Canadian legal system. Case law in the area of metadata and electronic evidence in general has expanded greatly in the last ten years. Concentrating on rulings related to admissibility, the leading cases on electronic records6 are presented, including those related to the business records exception to the hearsay rule, best evidence rule and weighting of evidence, use of standards in authentication, and computer- generated versus human-generated electronic records.

2.0 Structure of the article

A historical review of archival and records management literature, beginning with the legal aspects of traditional records and ending with recent work on metadata, is discussed. Then, an overview of the Canadian legal system is given, including how statutory law and case law work together. Next, the main types of evidence – comprising real, documentary, and demonstrative evidence – are presented. Metadata – which include system, substantive, and embedded metadata – are then explored and are shown to be part of real evidence as well as documentary evidence. Finally, the leading Canadian case rulings related to metadata are examined.

3.0 Perspectives on records and the law over time

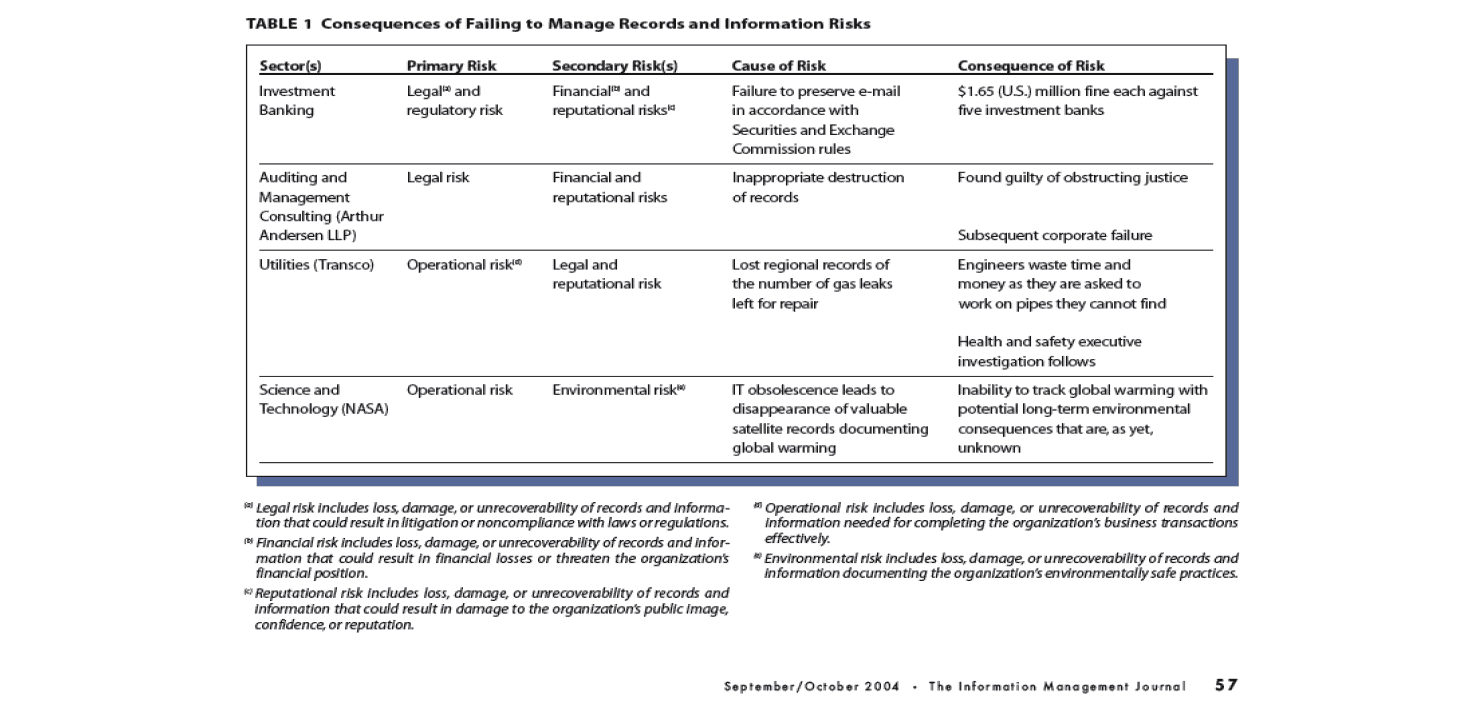

Archival and records management literature has explored the legal aspects of records from multiple perspectives, including how to maintain records as trustworthy potential legal evidence, the uses of metadata for electronic document discovery, and various typologies to describe and explain metadata. The following section is a review of literature to assist records and information management (RIM) professionals in understanding the foundational knowledge of archival science as well as recent evolutions in the archival and RIM fields.

3.1 Authenticity of documents

Archivists and records managers are keenly aware of the need to manage records as potential evidence. As explained in Sheppard’s 1984 article, “Records and Archives in Court,” archivists need to understand the criteria for admitting records in court as evidence7, including those of authentication, best evidence, and hearsay rules of admissibility. These key aspects of documentary evidence are deeply embedded in archival science; indeed, central archival concepts of authenticity, integrity, and reliability are built on and derived from Western common and civil law systems.

Roman law held records to be trustworthy because they were kept in inviolable places by trusted custodians such as an archives. The spread of Roman law and the credibility it attributed to records led to widespread forgery. To control for improper and untrustworthy records, specific rules were created that are at the root of basic evidence in common law systems: the best evidence rule and the authentication rule8.

Forgery became a common problem, to the point that specific rules had to be introduced to prevent it, such as a requirement of great formality in the creation and structuring of the original record, and a requirement of authentication by experts whenever a record was offered as proof of a fact at issue9. This adaptation of the law to the circumstances of the times is at the root of the two basic rules of evidence in common law: 1) best evidence rule, which gives a preference for an original document when a document is submitted as evidence and 2) the authentication rule, which requires that to adduce a document there must be evidence provided that the document is what it purports to be10.

The methods of authenticating records have changed over time. Archival documents were authenticated by their chain of custody under Roman law. Sir Hilary Jenkinson believed that records were “authenticated by the fact of their official preservation11.” To him, records’ history of legitimate custody was a sufficient guarantee that a record was trustworthy. Another key archival scholar challenged this faith in the chain of custody and stated that records must be tested for indications of their authenticity through studying their provenance and elements of their form (diplomatics)12. Authenticity may be defined as “the quality of a record that is what it purports to be and that is free from tampering or corruption13.” In current Canadian statutory law, authenticating electronic documents is a burden placed on the party adducing the document, who must provide “evidence capable of supporting a finding that the electronic document is that which it is purported to be14” or, stated another way, “capable of supporting a finding of authenticity.”

Archival science and diplomatics provide a model of “record” and a way to define the authenticity of a record. A record is defined as a document made or received in the course of practical activity and set aside for future action or reference15. To establish its authenticity, the record’s integrity and identity must be demonstrated. InterPARES 3 project defines integrity as “the quality of being complete and unaltered in all essential respects” while identity is “the whole of the characteristics of a document or a record that uniquely identify it and distinguish it from any other document or record. With integrity, [identity is] a component of authenticity16.”17

For records created in a digital environment, authenticity is inferred from evidence on how the records have been created and maintained18. In common law legal systems, documentary evidence must be authenticated to be admissible at trial. Authenticity, established through processes of authentication, is codified in our legal systems through statute and common law. Authentication of documentary evidence is accomplished through witness testimony, expert analysis, non-expert opinion, or, in the case of public documents or other special types, circumstances of record creation and preservation19.

3.2 Metadata and electronic documents

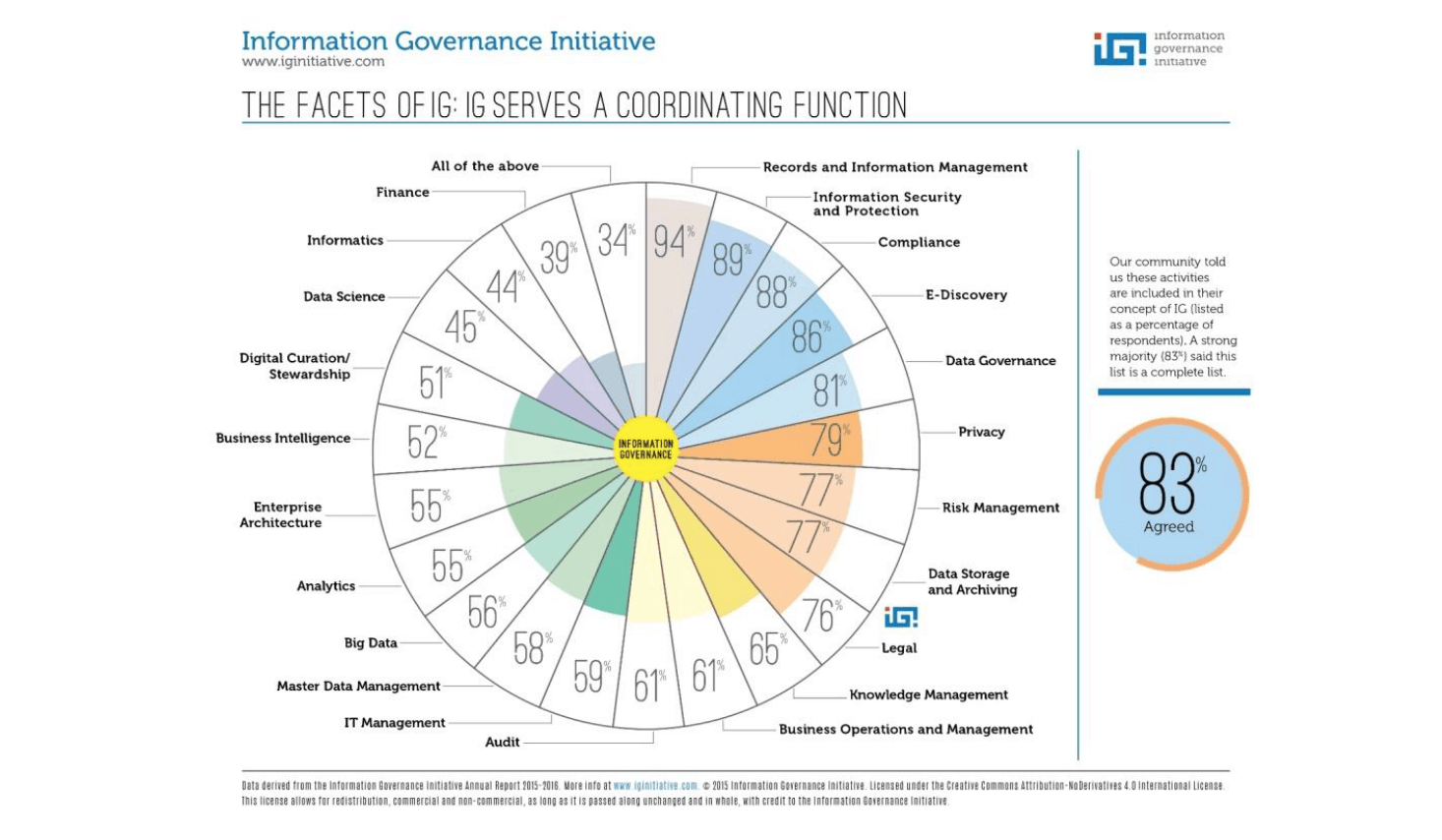

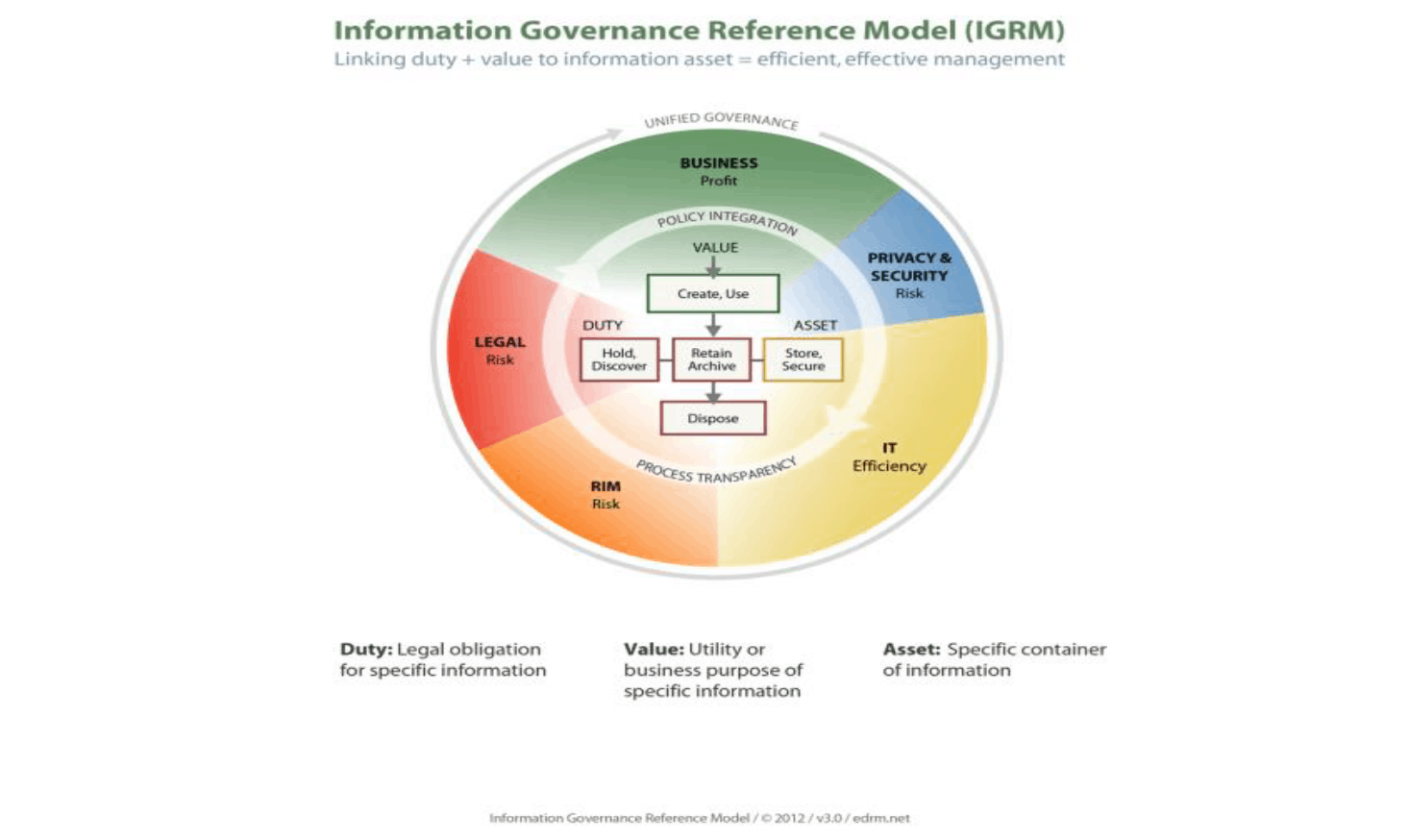

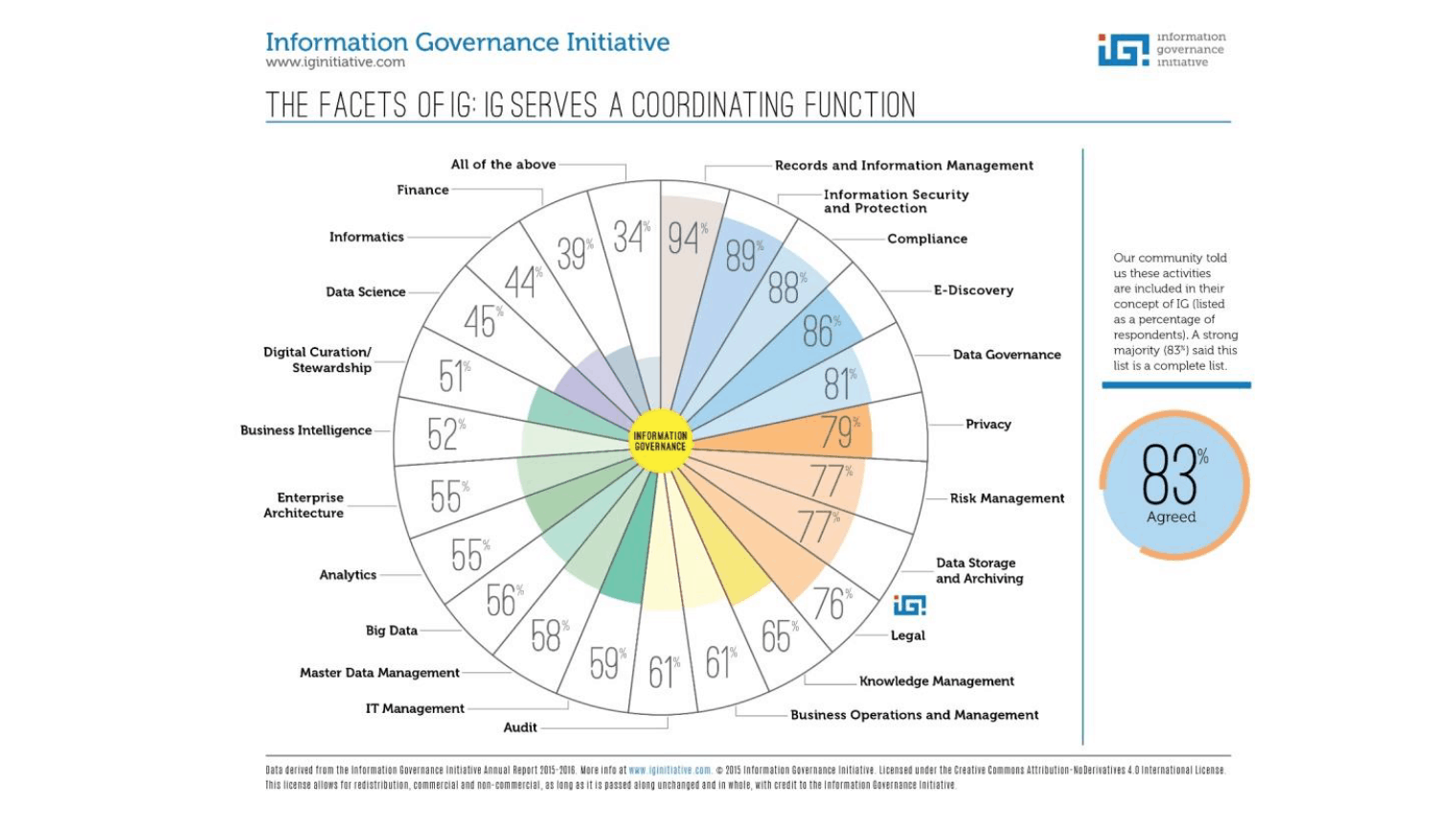

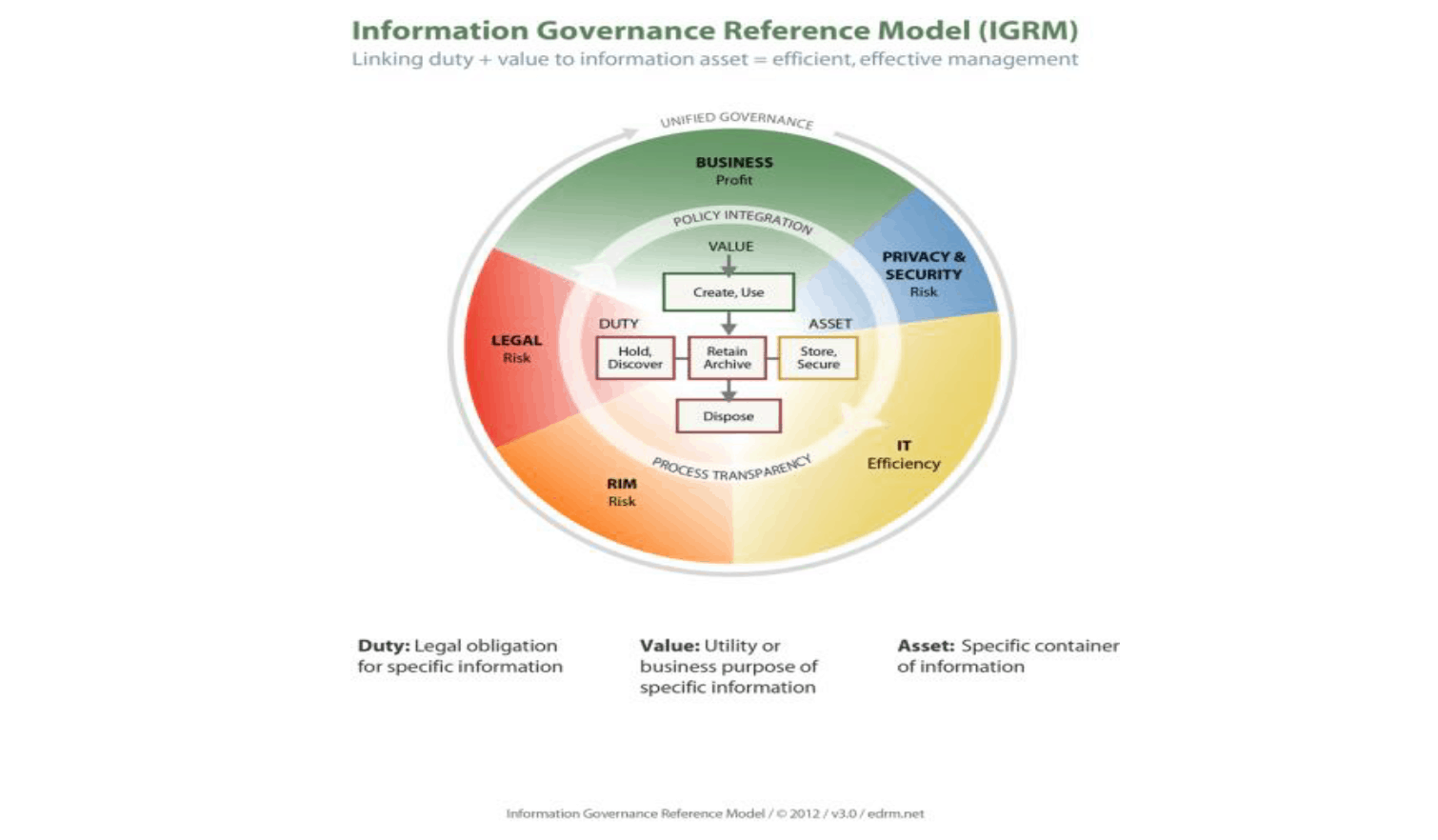

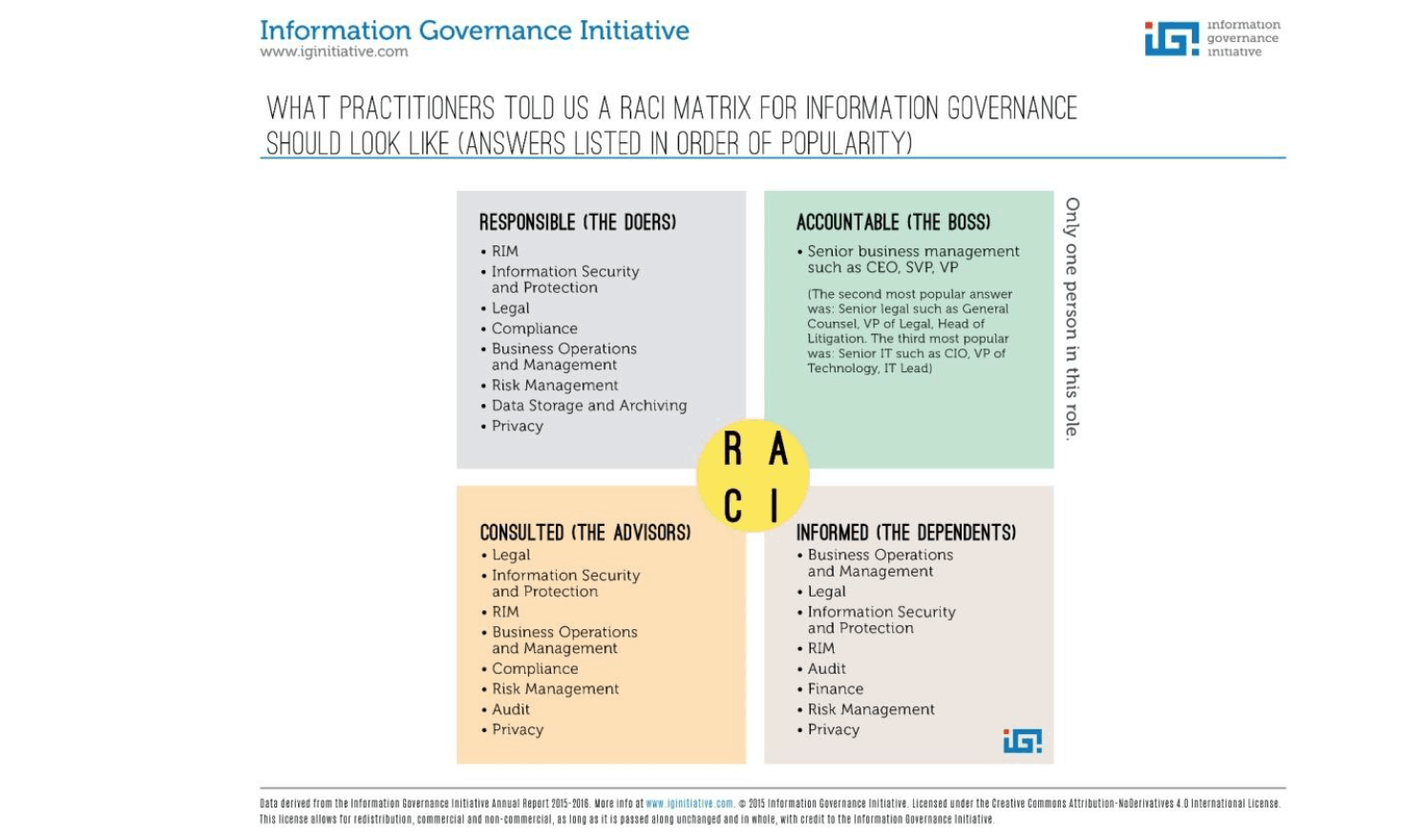

In records management (RM) literature , metadata plays many roles over the record life cycle. The Information Governance Maturity Model, which incorporates the Principles® from ARMA International, explicitly cites the role of metadata in an effective information governance system, including the higher levels of principles such as integrity and compliance. Metadata assists in ensuring that information generated has reasonable and suitable guarantees of authenticity and integrity (Integrity Principle) and that an information governance program complies with laws and organizational policies (Compliance Principle)20. The Principles® are a well-known guide for records professionals seeking to assess and improve how records and information are created, managed, and used in organizations21.

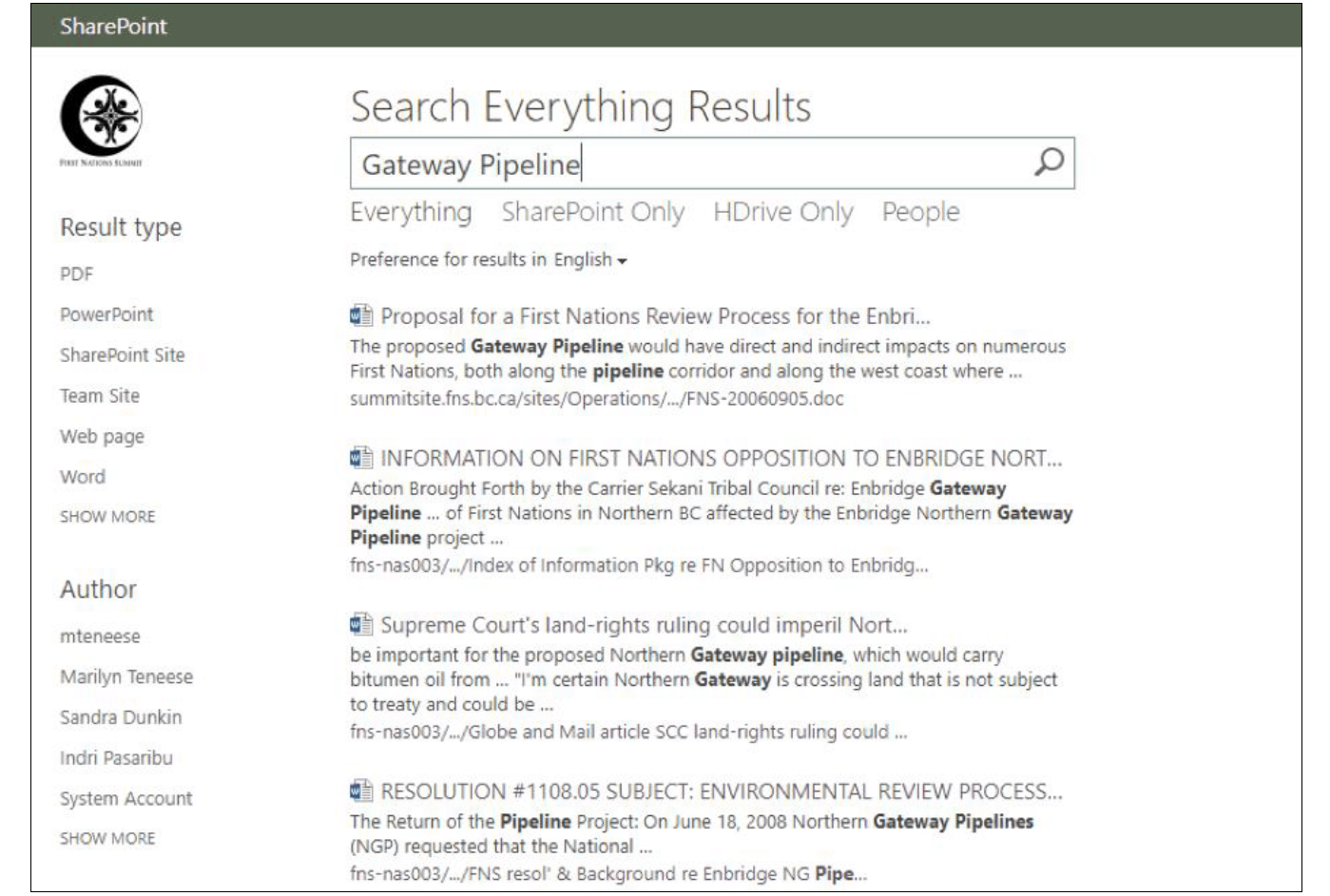

Ensuring timely, efficient and accurate retrieval of records, including for legal discovery, is another frequently discussed concern that metadata addresses. Early treatments of metadata for legal purposes tended to draw analogies to analog records. Metadata was initially described in RIM literature using bibliographic schemas, such as the three-way distinction between descriptive, structural, and administrative metadata used widely in the library and archives sphere. This typology of metadata put the focus on availability and retrieval. Descriptive metadata describes a resource for purposes such as discovery and identification. Structural metadata indicates how compound objects are put together.

Administrative metadata provides information to help manage a resource25. This library- informed conception of metadata simply extended the typical tasks of bibliographic retrieval to include legal discovery.

A mid-2000s RIM report also used paper documents as an analogy to describe metadata when considering records as legal evidence. Writing on electronic records as evidence, Mason distinguished between two types of metadata. He used analog document examples to explain the metadata associated with electronic documents using a binary distinction between explicit and implicit metadata. He described explicit metadata as metadata that comes from perusing the paper itself, “such as the title of the document, the date, the name of the person that wrote it, who received it and where the document is located.” Implicit metadata was described as automatically originating from the application software, or being supplied by the records creation. Examples of implicit metadata include “types of type used, such as bold, underline or italic; perhaps the document is located in a coloured file to denote a particular type of document, or labels on file folders26.”

A little over ten years ago, it was common to think of metadata through the lens of a paper document world and to apply existing knowledge on bibliographic and library cataloging systems to explain metadata. While analogies to paper or analog documents are useful for describing the relatively new concept of electronic metadata, it arguably also limits the discussion on metadata drastically. It is certainly useful to know where to look for metadata to assist with a certain task, such as discovery, or to understand that some metadata may be hidden or implicit. However, larger questions such as who creates metadata and how to consider it in legal proceedings are left unanswered. Indeed, courts and the legal community were finding Electronically Stored Information (ESI) and metadata to be less straightforward than previous paper records.

Sedona Canada, coming after the US Sedona Conference Principles of 2007, explicitly acknowledged that ESI was a different animal from analog records. The working group opened its best practices document on electronic discovery in 2008 by explicitly stating: “ESI behaves completely differently from paper documents.”… [It] “can be mishandled in ways that are unknown in the world of paper27.” They also noted that ESI may be created, copied, and distributed without active human involvement28. Unlike paper documents that record or reflect human statements or intentions, electronic information is not necessarily generated as the result of human activity.

As a consequence, the courts and judges seemed unsure on whether computer-generated information such as metadata had anything in common with documents or documentary evidence. R. v. Hall (1998) was an early case in Canada that recognized that computer information was generated with no direct human intervention was admissible as real, rather than documentary evidence. In the mid-2000s, courts on both sides of the border were considering how to treat “hidden” or “embedded” information (i.e. metadata). Courts applied federal and provincial/state rules of court30 and determined with Williams v.

Sprint/United Mgmt Co. (2007)31 in the US and Hummingbird v. Mustafa (2007) in Canada32 that metadata is part of electronic documents and should be produced as part of discovery. In considering discovery questions, the Hummingbird v. Mustafa case ruling determined that metadata should be produced but it also noted that not all metadata will be useful for understanding a document.

The Sedona Principles of the US also concentrated on discovery and production, and they outlined best practices on handling electronic documents. Regarding metadata, the US Sedona Principles stated that metadata can be embedded in the document or stored external to the document on the computer’s file system33. The primary distinction made in US Sedona Principles was between two types of metadata: application and system.

Application metadata is “embedded in the file it describes and moves with the file when it is moved or copied.” System metadata, on the other hand, is stored externally. “System metadata is used by the computer’s file system to track file locations and store information about each file’s name, size, creation, modification, and usage34 35.” This description of metadata moved away from a paper-oriented understanding of documents and shifted focus to the different metadata-generating layers of the computer system.

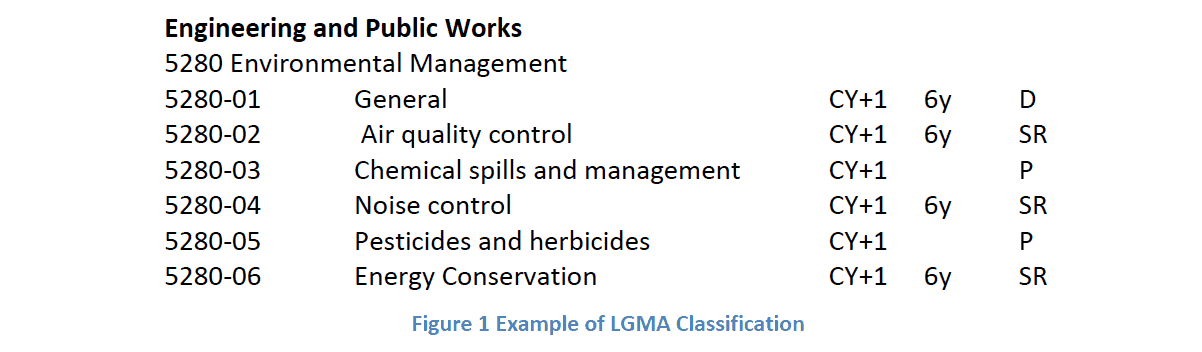

A different articulation of metadata was elaborated in an ARMA International Education Foundation (AIEF)-commissioned report on “Metadata in Court: What RIM, Legal, and IT Need to Know)36 Isaza described three types of metadata: substantive, system, and embedded. This typology was taken from the American case Aguilar v. Immigration Customs Enforcement Division (2008):

- Substantive metadata is application-based that were not necessarily intended for adversaries to see. Examples of substantive metadata include document author edits, reviewer comments,

- System-based metadata includes information automatically captured by the computer system. Examples of system-based metadata include author name, date and time of creation, and timestamps of

- Embedded metadata consists of text, numbers, and content that is directly input but not necessarily visible on output. Examples of embedded metadata include spreadsheet formulas or hyperlinks to other documents, charts37

While Isaza’s report was on discovery and spoliation and not on issues of admissibility, the metadata distinctions that he included are useful beyond their purposes for discovery.

System metadata (e.g. file names and extensions, sizes, creation dates) is most relevant for authentication purposes. This data could be crucial to authenticating the record for any purpose where authenticity of the record is paramount, like archival or historical uses38 39.

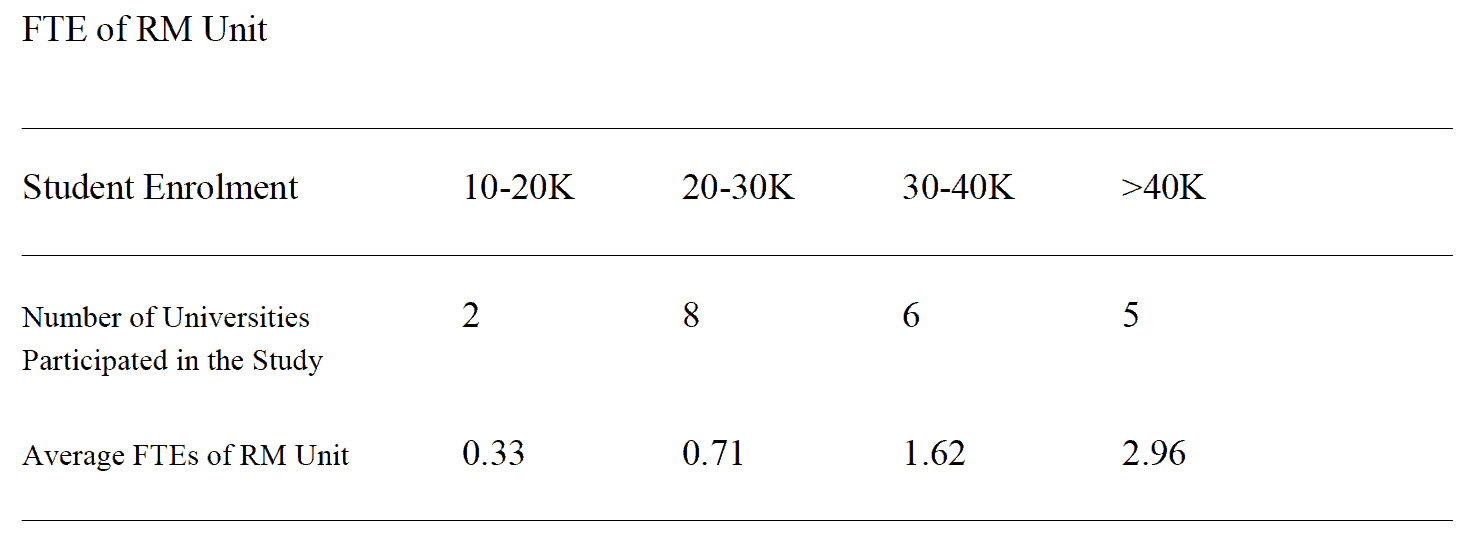

Compared to the role of metadata in assisting with timely discovery, there is much more limited discussion in RIM literature on metadata and its role in legal cases, including the role of metadata in establishing the authenticity of records for admissibility purposes. This may be due to the fact that very few records professionals are called upon as expert witnesses to authenticate digital records before a trier of fact in a court case. In a transnational survey of records professionals, only about 5% of 293 respondents had ever been required to authenticate digital records before a court during the course of their career. In follow-up interviews, some respondents commented that they were more likely to be involved in the production phase, while IT professionals were likely to be called to act as experts of the system40.

In Canadian court cases, this experience also holds true. Records professionals are infrequently called upon to authenticate digital records or the systems in which they reside. A recent exception includes R. v. Oler. This case is discussed further in 5.3: Use of standards in authentication.

Contributions to RIM literature from records professionals with direct experience in authenticating digital records or testifying to the integrity of their records system would be meaningful and useful to the records management community. In the meantime, recent court rulings on electronic evidence give important insight into how metadata is being addressed and considered in today’s Canadian courts.

4.0 Legal foundations

Having explored the contributions of archival and records scholars on the topic of the legal uses of records and metadata, it is also important to understand the legal context of how Canadian legal decisions are made. The following section is intended to outline the basic elements of the Canadian legal framework for RIM professionals who may not be experts in case law. The main sources of law are explained, including the distinctions between federal and provincial Evidence Acts. The different types of evidence as well as admissibility rules are described. RIM professionals have a particular contribution to make in understanding and correctly characterizing how the ESI was created. Understanding the wider context of law can greatly assist RIM professionals in ensuring that the appropriate rules of evidence are applied when and if they are called upon to assist in a legal trial.

4.1 Statutory and case law

As is the case in most common law jurisdictions, evidence law in Canada comes primarily from common law, which does not vary among jurisdictions. Each court applies essentially the same evidence law, but each jurisdiction also has evidence acts (statutory law) that may modify or supplement common evidence law41 Two main sources of law are 1) enacted statutes and 2) cases adjudicated by judges in courts of law. Legislative bodies, including the Parliament of Canada, the ten provincial legislatures, and the three territories, are granted the legislative authority to enact statutes42 These sovereign legislative bodies may delegate authority to a subordinate body to create rules, as Ontario’s Courts of Justice Act delegates rule-making authority to the Civil Rules Committee43. Rules of courts are therefore a type of subordinate legislation and are a part of statutory law.

In addition to statutory law, case law is the second major source of law. Case law comes from the written decisions of courts on particular matters. Judges’ decisions, and the stated reasons for those decisions, serve as precedence for future courts deciding on similar situations. Courts are bound to follow precedent cases, and the body of case law develops to give guidance to judges as they decide on contemporary matters44.

Statutes and regulations, such as court Rules of Civil Procedure, operate together to form a code of procedural law; while they work in tandem, the majority of procedural law in Canadian Superior Courts is set out by the Rules rather than by any statute45. The Civil Rules Committee has delegated legislative authority to make rules in relation to the practice and procedure of the Court of Appeals and Superior Court in all civil proceedings for the relevant jurisdiction (federal, provincial)46.

The rules of court may not conflict with what is stated in an Act, such as the Evidence or Interpretation Act. However, they may supplement what is provided in the Act by further articulating practice and procedure47. Rules of court give guidelines to judges and lawyers on how things shall be done during a trial and codify expectations and common understandings.

Federal matters and criminal cases are tried under the Canada Evidence Act, and each province and territory has its own evidence act for civil and provincial matters48. Issues specific to electronic evidence have been largely coordinated among the jurisdictions through the Uniform Electronic Evidence Act49. Through the adoption of Uniform Electronic Evidence Act provisions, the focus was shifted away from satisfying authentication and best evidence of a particular record. Instead, the focus moved to inferring trustworthiness from the integrity of the electronic system. The adducing party is required to show that the system was operating as expected when the record was created. If this is done, the evidentiary requirements are satisfied50.

4.2 Types of evidence

Evidence is submitted in the form of either oral testimony by witnesses or as real evidence51. As established by statutory law and case law, evidence may be of three main types: real evidence, documentary evidence, and demonstrative evidence. The first type, real evidence, speaks for itself. The trier of fact (judge, jury, or other adjudicator) can use their own reasoning to understand real evidence and can draw conclusions based on what is presented. In a murder trial, a gun registered to the accused may be real evidence52.

The second type, documentary evidence, is evidence that is offered for the truth of the statement it contains53. It is not the fact that the evidence is in a document form which makes it documentary evidence. The crucial characteristic of documentary evidence is that it is “a recording … of an out-of-court statement of fact made by a person who is not called as a witness, that is tendered for the truth of the statement it contains54.”

The third type, demonstrative evidence, is evidence that is not strictly material to the case but which can help the trier of fact interpret the material facts55 Digital animations or other computer-generated images are examples of demonstrative evidence but they tend to require expert testimony to accompany them. Tests for expert opinion rules will usually apply, including cost-benefit analysis of whether the demonstrative evidence helps the jury or trier of fact to understand the evidence without creating a prejudicial effect and distorting the fact finding process56. Demonstrative evidence can in turn be testimonial (e.g. expert witness), documentary (e.g. medical illustration and photographs of an injury), or real (e.g. videotaped re-enactments of events to contextualize witness testimony)57.

A leading case on electronic records acknowledged that metadata may complicate these boundaries of evidence. In Saturley v. CIBC World Markets, Justice Wood stated, “It is possible that a given item of electronic information may have aspects of both real and documentary evidence58.” An email, for instance, has automatically generated metadata that records when the message was sent and from which computer. These “statements” are not made by a person who could be called as a witness and cannot be properly called documentary evidence. The email also has statements made by human declarants in its contents such as the message text itself. As such, an email has components that may be either real or documentary evidence.

4.3 Admissibility rules

The basic principles of evidence at trial include admissibility, weight, and standards of proof. These apply regardless of type of evidence. Admissibility and weight are formally kept separate. Admissibility is the judge or court’s determination that the evidence can be presented during the trial. The judge (or trier of law) determines if the evidence is relevant to a material fact in the case59. The item must have some tendency to make the existence of a fact in the case more or less probable. Admitted evidence becomes part of the body of evidence that goes before the trier of fact (either a judge or jury) who must, at the end of the trial, determine the “weight” of evidence. This includes determinations of which parts are accepted and which are rejected based on the standard of proof; for civil cases, the party admitting the evidence must prove that the evidence is true based on the balance of probabilities, while for criminal cases, the measure used is beyond reasonable doubt60.

In order to be admitted as evidence in court, potential evidence must pass various tests of admissibility. Some admissibility criteria and appropriate rules of evidence apply to all types of evidence. For example, rules of materiality and relevance apply without regard to evidence type61. Evidence must assist the trier of fact in drawing the necessary inferences (weight), and it must be relevant to the issues or events in question (relevance).

Another admissibility rule, the best evidence rule, says that if there are two records with the same content, then the one that is the “original” will be accepted. Electronic documents can fulfill the best evidence rule if the adducing party provides evidence that speaks to the “integrity of the electronic documents system by and in which the electronic document was records or stored62.” Proof of integrity can be established through proof that the storage medium (e.g. hard drive, operating system) was operating properly, proof that the document was recorded or stored by the other (“adverse”) party63, or proof that the document was recorded or stored in the ordinary course of business64. Integrity can be proven by an affidavit or expert evidence65. Integrity of the system can also be proven by providing evidence that current standards, procedures, and practices were adhered to66. Finally, a print out of an electronic document that was “manifestly or consistently acted upon” as a record, can be deemed as best evidence67.

Other rules of admissibility differ according to the type of evidence considered68. The hearsay rule and its exceptions, for instance, only apply to statements that are made by humans. The hearsay rule prevents statements by a person who cannot be examined as a witness from becoming evidence in court.

Authentication of analog documents often involves having the author confirm that they created it or having a witness confirm that they saw the creation of the document.

Authentication of electronic evidence focuses on the metadata associated with the documents or on the metadata traces left behind when the document was created. The process of creating, saving and editing an electronic document leaves evidence fragments in the form of metadata that can be used to authenticate electronic evidence69.

4.4 ESI as real and documentary evidence

ESI may be admitted as real, rather than documentary, evidence. Underwood and Penner note that while the distinction between ESI as real or documentary evidence has been recognized in English and American courts, Canadian treatment of ESI as real evidence has been less uniform. They note that Canadian counsel and courts to date (i.e. 2010) have failed to properly characterize ESI as real or documentary at the outset of proceedings, leading to a failure in applying the appropriate rules of evidence to determine admissibility70. Properly characterized ESI entails an understanding of both how it was created and the purpose for which it is tendered. While legal counsel may ably address the latter question, it is in the realm of records and information management professionals to understand the former and to correctly characterize how the ESI was created so that the appropriate rules of evidence can be applied.

Evidence may be real evidence either for the purpose it is submitted or for the manner in which it was created. If either of the following conditions apply, the evidence should be submitted as real evidence:

- the ESI is not tendered for the purpose of the truth of its content, but rather for the fact that it existed or was found in the possession of a person;

- the information embodied in the ESI does not depend upon the interposition of a human observer or recorder between the external event and the ESI that captures the information about the event. This ESI results from an automated process, or is computer-generated71

ESI, metadata associated with electronic documents, or analog documents can all be admitted as real evidence when their purpose is to serve as proof of the fact of their own existence rather than for the purpose of providing the truth of the statements they contain72. An email and its associated metadata may be entered as real evidence if they are tendered as proof that the sender sent the communication at a certain time, or to link the statements contained in the email to the author73. However, if the email is submitted because of the contents of the message, it would be adduced as documentary evidence74. The purpose the evidence is intended to serve is more important than the form the evidence takes.

Canadian courts tended to treat ESI that is automatically generated in same fashion as documentary evidence and admit them under the exception to the hearsay rule, rather than admit them as real evidence75. However, since the publication of Underwood and Penner, several Canadian courts’ rulings, including the influential Saturley v. World CIBC Markets, have cited their work and have made finer distinctions between ESI as real or documentary evidence76. Saturley cited this useful passage from Underwood and Penner’s Electronic Evidence in Canada to explain the distinction:

A record that is created by a computer system whose function it is to capture information about cellular telephone calls would be introduced as real evidence, and the record could be relied upon for the truth of its contents without resort to any exception to the hearsay rule. Because the information that is captured (the date, time and duration of the call, for example) is recorded automatically without being filtered through a human observer, the condition for real ESI evidence is satisfied. It is also important to note that the information recorded is itself not an out-of-court statement by a human declarant, but rather it consists of objective information that is captured and recorded by an automated process.

On the other hand, if a record is created by a human sitting at a computer keyboard and entering data, the ESI embodied in the record could not be tendered as real evidence if it is offered for the truth of its contents, and its proponent would have to bring the record within the ambit of an exception to the rule against hearsay. The record would be documentary evidence, and subject to the same limitations as would apply to a conventional document. The information contained in the record has been filtered through a human observer, and the ESI reflects the human declarant’s out-of-court statements concerning what he or she observed, heard or did. It is not real evidence77.

When ESI is not properly characterized as either real or documentary, the unstated assumption is that ESI is documentary and, consequently, hearsay78. However, if ESI is automatically generated or may otherwise be characterized as real evidence, the evidentiary rules relating to documentary evidence need not be applied79 80.

Metadata is one of the most important sources of real evidence81. Some, but not all, metadata is automatically generated and, if properly characterized, need not be admitted as documentary evidence and need not meet the admissibility criteria for hearsay exceptions.

ESI as real evidence must have evidence to establish the authenticity and threshold reliability established to be admissible82. Threshold reliability exists on a spectrum, from “utterly unreliable to highly reliable.” The proponent offering the evidence must satisfy the judge that the information is, on the balance of probabilities, sufficiently reliable. It need not be error-free. Like documentary evidence, such matters of potential of error go to weight, not admissibility83.

The type of metadata can assist in correctly characterizing the evidence under consideration. A useful typology of metadata from the US Aguilar case was elaborated to assist in making evidence type distinctions. The metadata types of system, substantive, and embedded are created with varying levels of human input84.

System metadata is an automatic capture of data from the system that created the electronic document and is a type of real evidence that includes the date and time the file was created, as well as details on when the file was modified or viewed. System metadata does not record any out-of-court statements made by human declarants and is therefore not documentary evidence. This type of metadata changes readily and may be intentionally or unintentionally altered. To pass admissibility tests of reliability and authenticity of real evidence, system metadata often must be subjected to expert forensic analysis85.

Substantive metadata is also called application metadata, because it is generated by the application software. It captures information about the creation and editing history of the electronic document. This type of metadata shows prior edits or modifications to the file and includes formatting display rules like font type and line spacing. Depending on the type of information it captures and how it will be put to use, substantive metadata may be either documentary or real evidence86. When the metadata is captured automatically and used to show that a comment or text edit has been included, the metadata is usually considered real evidence. When the metadata is being admitted to prove the truth of the content of a comment or text edit, the substantive metadata would be considered documentary evidence instead87.

Embedded metadata is information that is part of the electronic document because the user placed it there. Examples include spreadsheet formulas, hyperlinks to other documents, a video clip included in a PowerPoint presentation, or even hidden cells or linking relationships in a database. Embedded metadata is rarely automatically generated by the computer system or application software; as such, embedded metadata is most frequently considered documentary evidence88.

5.0 Metadata and case law

Like digital information itself, case rulings on ESI and metadata have grown drastically as courts and judges have become more accustomed to admitting and weighing electronic evidence. RIM professionals can benefit from understanding trends of the courts such as the “principled approach” to the hearsay rule, the precedent-setting use of RIM professionals and Canadian and international standards in the authentication of evidence, and the potential for automatically-generated metadata to be adduced as real evidence.

Below, recent relevant case law has been conveniently grouped by theme or finding as it relates to the RIM profession.

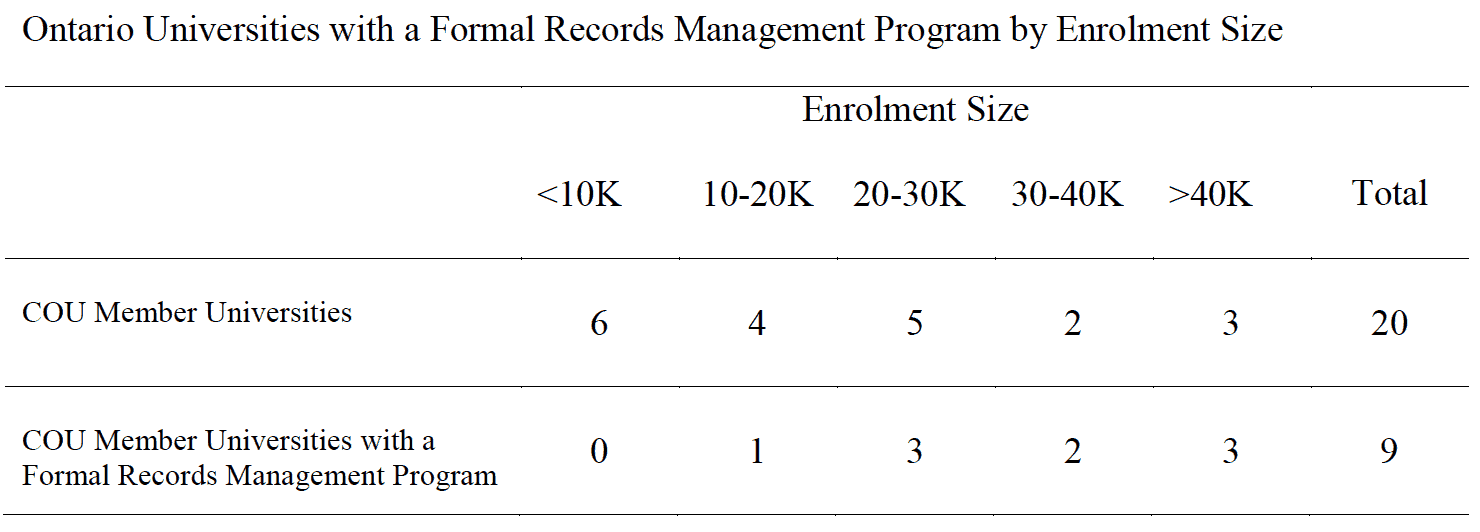

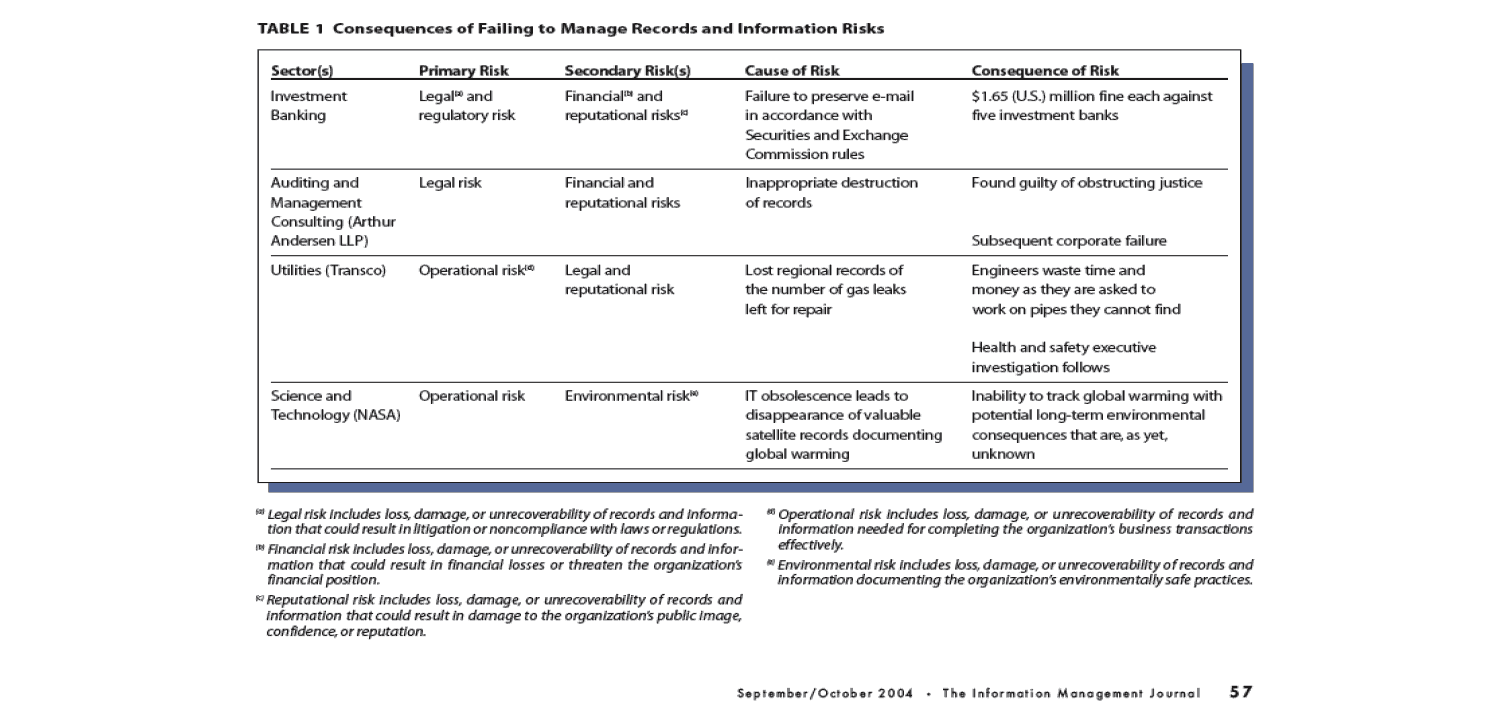

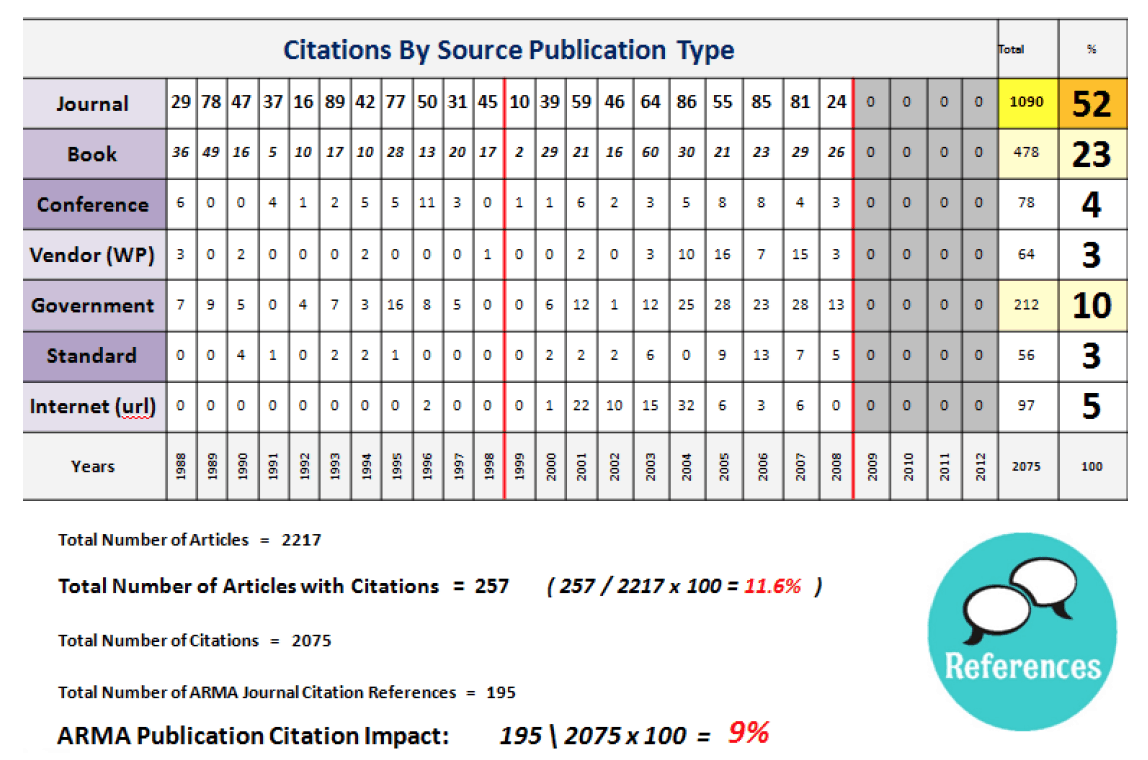

Federal, provincial and territorial case law has gradually been building a body of rulings concerning different types of metadata and types of ESI evidence. In the last ten years, there has been a marked increase in cases that consider questions of electronic evidence. Between the years of 1996 – 2006, nineteen cases dealt with electronic records89. In the last ten years from 2007 – 2017, 262 cases have considered ESI, metadata or computer evidence. The treatment of metadata has become more firmly rooted in Canadian case law. This section looks at the leading cases on electronic records under the business records exception to the hearsay rule, best evidence and weight, use of standards in authentication, and computer-generated versus human-generated electronic records.

5.1 Business records as hearsay exception

A recent and leading case in British Columbia systematically applied the federal Evidence Act to several documents that had been previously ruled inadmissible by a summary trial judge in a case of an insurance claim for disability payments. Certain portions of the presented evidence were ruled inadmissible as business records exceptions to the hearsay rule; in McGarry v. Co-operators Life Insurance90, the court reconsidered the ruling and specifically looked at attachments to a witness testimony, which are both paper documents such as printed policies and quotes and as well as emails.

The majority of the British Columbia Court of Appeal went through the exhibits and used the “principled approach” to the hearsay rule cited in RS II Film Distribution v. BC Trade Development Corp91. to consider reliability. Specifically, indicators of reliability include whether the source of the information, preparer of the document, and creation date are known, and whether there is anything on the document itself that indicates it was made in the “ordinary course of business92“. The majority of the BC Court of Appeal then went through each document previously ruled inadmissible as a business record exception, they applied s.42 of the Evidence Act93 to the affidavit and its accompanying documents, and they concluded which data establish that the record is reliable (chiefly, the date it was created and whether one of the businesses involved in the case produced the record, as indicated by signatures, document headers, etc.).

The majority of the BC Court of Appeal addressed the question of emails as business records, noting that the Evidence Act of British Columbia does not discuss electronic records or provide criteria for considering them as evidence. They noted that other provinces do, however, and other provincial Evidence Acts94 outline specific concerns regarding authenticity and requirements that the submitting party provide evidence of the integrity of the electronic document system. They noted that since the emails in this case were deemed inadmissible, along with the other documentary evidence, these tests of authenticity and integrity were not performed or considered95. The admissibility of the emails cannot be determined, because these issues were not addressed in the trial case.

However, the majority determined that because all of the evidence in this case was documentary, it was feasible and practical to make a fresh assessment of the evidence, including the evidence (such as the emails) previously declared inadmissible by the summary trial judge96. The decision thereby implicitly determined that the emails are documentary evidence, despite the barriers to determining their authenticity or the integrity of the electronic document system they were created on.

This case is largely cited in other cases for the finding in paragraph 81 that if all the evidence is documentary, it is feasible for an appeal court to make a fresh assessment of the evidence in the case97.

Other cases on the topic of admitting evidence under burden of s.31 or with evidence of authenticity, integrity and identity include R. v. MacDonald 2016 ABPC 142 at para. 27, R. v J.S.M 2015 312 at para. 53-54, R. v. Soh 2014 NBQB 20 at para. 31-32, R. v. K.M. 2016 NWTSC 36 at 57-60, R. v. Bernard 2016 NSSC 358 at para. 50-58.

5.2 Best evidence, low threshold for admissibility, weight, authentication98

The three aspects of the admissibility of documents are the hearsay rule, authentication, and the best evidence rule. Documents must be adduced for the truth of their contents to be classified as hearsay and to be admissible under the business records or other exception.

There must be evidence that the document is what it purports to be (authentication rule), and that it fulfills the preference for the original of that document (best evidence rule)99. These aspects of documentary evidence have been blurred in court rulings, and, due to the generally low threshold in Canadian evidence law admissibility, any potential for error or suspect quality in the reliability of the evidence will usually go to weight, especially in civil cases100.

Several rulings in the last ten years have stated that concerns about completeness and integrity can be dealt with at trial when the trier of fact determines the appropriate weight to give the evidence. Additionally, questions about whether the presented evidence meets the best evidence rule also do not bar the evidence from admission. These questions are also resolved at the end of the trial during the process of weighting the evidence.

Some examples of these rulings are:

BL. v. Saskatchewan (Social Services)

All of these inherent frailties and features of the IEIS [Integrated Electronic Information System] records do not make them any less a record of the act, transaction, occurrence or event. The frailties may go to weight or ultimate reliability but do not exclude the records as a business record101.

R. v. Hamdan

[T]he best evidence rule has been relaxed, in part to address technological changes over the past 50 years; the standard is no longer stringent. Where the original document is not in hand, the best evidence rule does not bar admission of secondary evidence of the document, even where it may be incomplete or inaccurate. Concerns about completeness and integrity can be dealt with at trial when the trier of fact determines the appropriate weight to give the evidence102

Leading Canadian legal scholars also note that the best evidence rule has decreasing value in the modern era. Authentication, the main requirement for admissibility, is a relatively low threshold to achieve. Authors of “The Law of Evidence in Canada” write, “[t]he modern common law, statutory provisions, rules of practice and modern technology have rendered the [best evidence] rule obsolete in most cases and the question is one of weight and not admissibility.”103

Paciocco, the co-author of both Canada’s leading text in evidentiary law as well as a frequently-cited text on electronic evidence,104 notes that if a document is authenticated, it is admissible even though some of the information in the document may be inaccurate. The potential for inaccuracy is a matter of weight, not admissibility. If an electronic document may have been altered or have inaccurate metadata, the potential imprecision should not affect the admissibility of the document105. Admissibility is a threshold test, and judges prefer to admit evidence and then weight it all at the end when credentials and believability of witnesses or experts can be established better106.

Numerous recent cases have drawn on Paciocco’s articulation of the low threshold of admissibility and “antiquated best evidence” statements to admit electronic records and to consider reliability, best evidence, and questions of the integrity of the system as factors in weight at the end of the trial. For example, R. v. C.L. (2017) considered the admissibility of copy-pasted and printed-out copy of an instant messenger (IM) conversation, including the inaccurate time-stamp metadata. As documentary evidence, the judge accepted the printout as best evidence and determines that witness confirmation that it is a true reflection of the original IM conversation is sufficient authentication, noting that the low threshold for admissibility has been met.

The common law imposes a relatively low standard for authentication; all that is needed is “some evidence” to support the conclusion that the thing is what the party presenting it claims it to be. As Paciocco states, for the purposes of admissibility authentication is “nothing more than a threshold test requiring that there be some basis for leaving the evidence to the fact-finder for ultimate evaluation107.”

Similarly, in R. v. Hirsch, the majority of appeals judges denied an appeal of a criminal code conviction based on three claims, including that the documentary evidence had not been authenticated108. This included screen captures of digital photographs on a Facebook page. This court determined that due to the low threshold of authentication, it was acceptable to accept witness testimony that they saw the post or have some other reasonable basis for believing the screen capture to be what it purports to be109.

I am not persuaded by Mr. Hirsch’s arguments on authentication and the related issue of authorship. In my assessment, s. 31.1 of the Canada Evidence Act is a codification of the common law rule of evidence authentication. The provision merely requires the party seeking to adduce an electronic document into evidence to prove that the electronic document is what it purports to be. This may be done through direct or circumstantial evidence…. Quite simply, to authenticate an electronic document, counsel could present it to a witness for identification and, presumably, the witness would articulate some basis for authenticating it as what it purported to be…. That is, while authentication is required, it is not an onerous requirement110.

Other cases on the low threshold for admissibility or the “antiquated” best evidence rule include R. v. Dennis James Oland, 2015 NBQB 245 at para. 43, R. v. Clarke, 2016 ONSC 3564 at para. 53-55, R. v. Avanes et al., 2015 ONCJ 606, and the labour arbitration ruling of Thacker v. Iamaw, District Lodge 140, 2016 CanLII 62600 (BC LA) at para. 52-54.

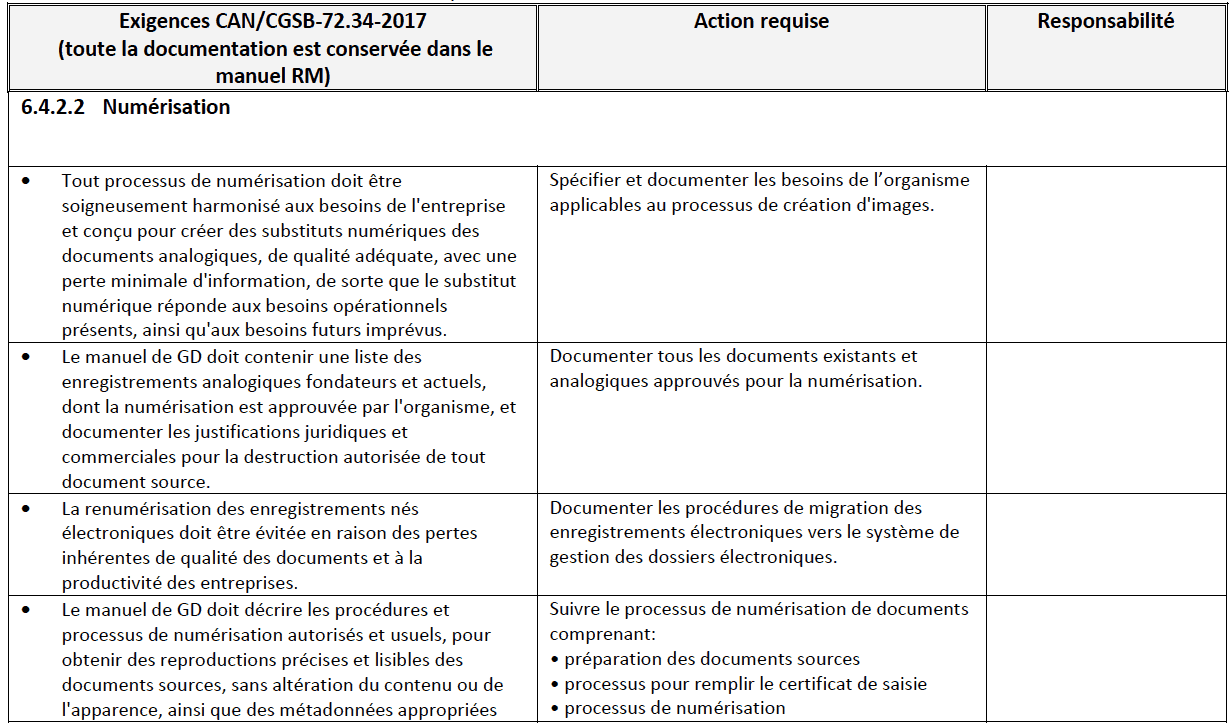

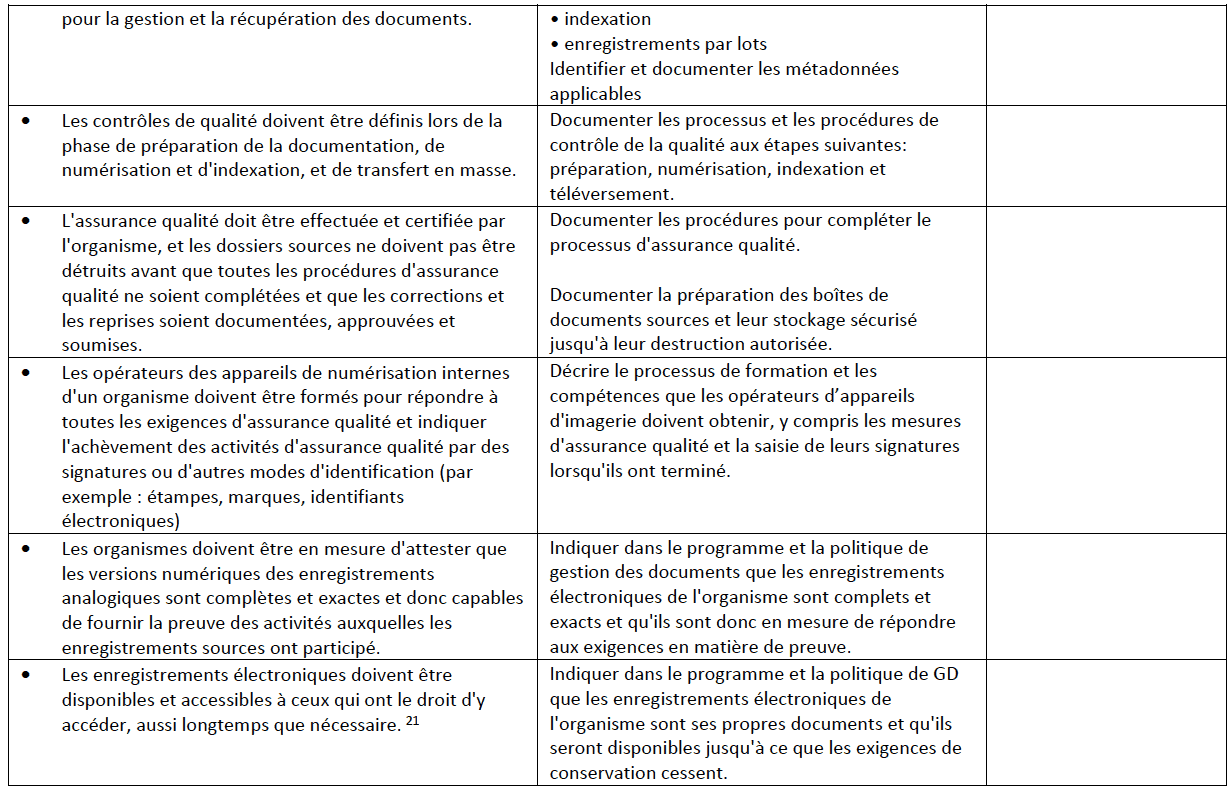

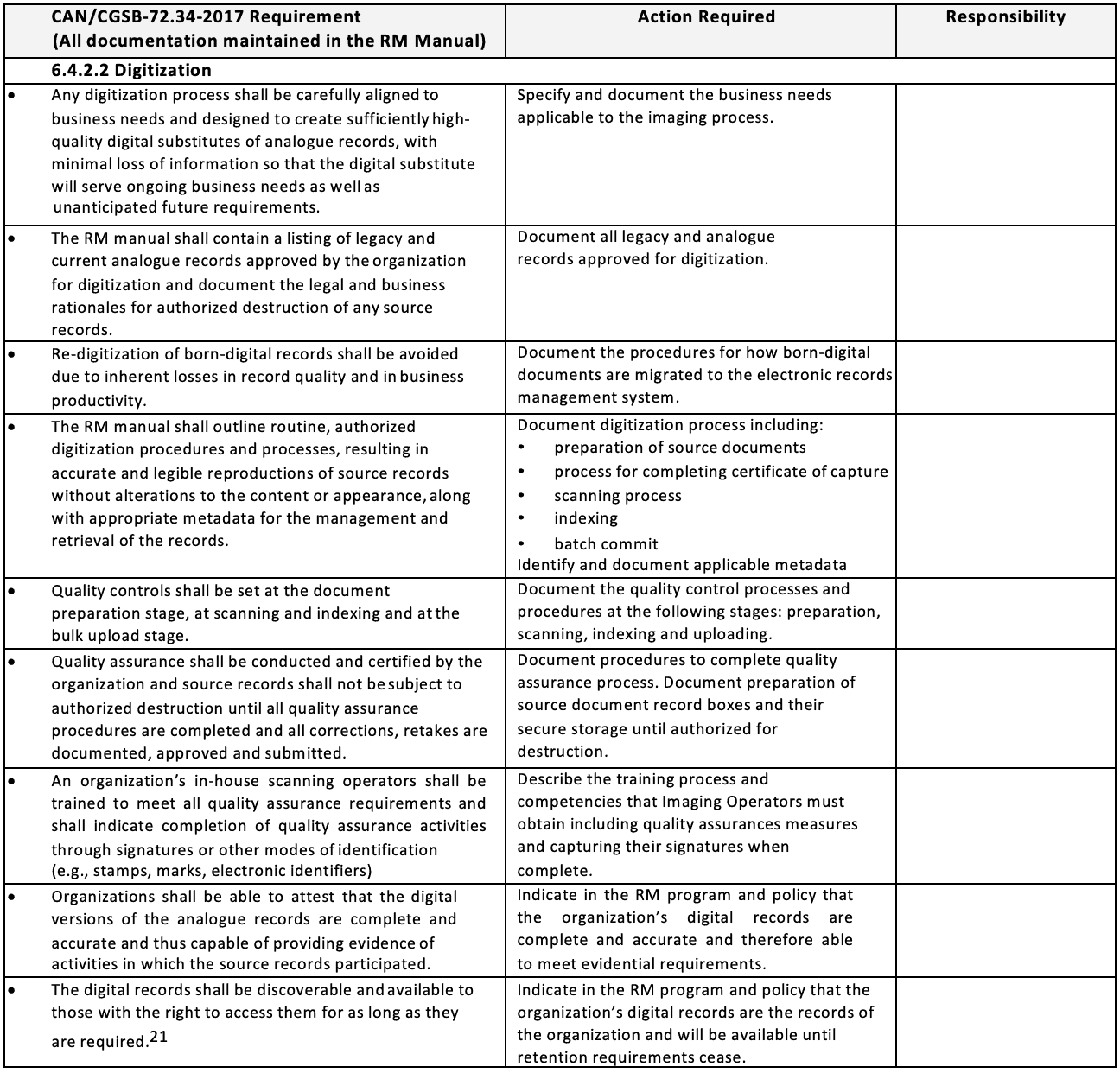

5.3 Use of standards in authentication

Compliance with standards such as the Canadian General Standards Board, CAN/CGSB- 72.34-2017 Electronic records as documentary evidence is one of the ways to determine if electronic evidence is admissible. According to s. 31.5 of the Canada Evidence Act,111 electronic documents that are created or stored in accordance with a standard can be considered authenticated and admissible. This was also recently confirmed in case law through the Voir Dire ruling of R. v. Oler112.

- v. Oler is an impaired driving criminal case where the facts must be proven beyond reasonable doubt. In this case, the evidence of the breathalyzer records of the Calgary Police Service were ruled to be admissible. The testimony of their records manager professional provided an expert opinion as to the integrity of the recordkeeping system they were created in. The expert explained that the records were created in accordance with their procedures manual which included security protocols and quality assurance processes; and that the electronic records management system (ERMS) system contained a permanent audit trail. Further, the ERMS is a DoD 5015.02 certified record system. The court ruled that these records were made in the usual and ordinary course of the business and that all evidentiary rules of authenticity, integrity and reliability had been satisfied because they were created in compliance with CAN/CGSB-72.34-2005113. A “live” document that could be updated (was not in a fixed form) was ruled admissible as a business record but the judge noted that weight should consider that it does not meet the same CAN/CGSB-72.34-2005 standards114.

5.4 Computer-generated versus human-generated

As noted earlier, courts and judges have struggled with how to treat electronically stored information. A key distinction discussed in numerous cases is the determination of how or by whom the information was generated. If the computer information was generated automatically, the evidence is often – but not always – considered to be real evidence. Real evidence needs to be authenticated, but it does not need to meet best evidence or hearsay exception rules.

If the ESI is not automatically generated and was instead created as the result of human intervention, the evidence is generally adduced as documentary evidence and must meet the relevant admissibility criteria.

Desgagne v. Yuen (2006) was a motion seeking the production of the plaintiff’s home computer hard drive and other devices, including the electronic documents, metadata, and internet browser history stored on them115. The court addressed whether metadata is a document, noting that “[t]he information being sought does not fit the ordinary or intuitive concept of a document, electronic of otherwise116.” The data being considered was an automatically generated record of the user’s activities that was not printed nor used in the ordinary course of any business. In spite of these facts, the court noted that the metadata is “information recorded or stored by means of [a] device and is therefore a document” under the BC provincial Rules of Court under Rule 1(8)117.

In seeking to produce a hard drive, it is not necessary to determine whether the ESI is real or documentary evidence. Instead, the metadata must have probative value and be relevant to the facts of the case. In Desagne, the judge stated that metadata that was automatically generated could be considered a document but denied the production order because the electronic files and metadata was not demonstrably relevant and the usefulness of metadata and browser history do not offset privacy concerns118. This case is widely cited for the relevancy limits it places on production orders for metadata and electronic evidence.

In some cases, it is not entirely straightforward whether the data or metadata was generated by a human or by a computer. The Animal Welfare cases considered the situation of scripts. The defendants119 sought to enter evidence of databases, reports generated from SQL scripts, Excel formatted databases or generated outputs from these databases, printed graphs, and screenshots. Some of this evidence – specifically the Sales data and the Customer data that were extracted from a database using SQL scripts – was offered to the court as real evidence.

The plaintiff argued that the scripts used to generate reports show evidence of human skill and experience and were subject to error, making them subject to hearsay admissibility tests. The judge determined that the tests needed to take place on the data, not the scripts, and stated that scripts retrieve the data but do not change the data120. The data were automatically captured by the computer system and are not out-of-court statements.

Accordingly, only authentication was required for admissibility121.

A later ruling122 revealed crucial details about script creation. During this case, the questionable integrity of the database was discussed, including chain of custody. The case also considered testimonial evidence from the person who created the scripts that extracted the data being entered into evidence. The script writer admitted that she was instructed to continue working on the script until it generated favourable results to the plaintiff, and she was in the employment of the plaintiff123.

Scripts are human-created and can be tampered with to achieve a human desired outcome. In this case, the judge did not re-determine the nature of the evidence but instead used different evidence to reach his final ruling124. Ultimately, concerns on the reliability of the script-generated reports were considered during the weighting of the evidence.

Once metadata or electronic information has been determined to be real evidence, Saturley, supra considered how to sufficiently establish the admissibility of such evidence. The party offering the evidence needs to establish that the information was automatically generated. They need not give evidence that the computer information is error-free. The court held:

The first step in the admissibility analysis is to determine whether the party offering the evidence can establish on a balance of probabilities that it fits within the parameters of real evidence as discussed above. That means, it must be data collected automatically by a computer system without human intervention. It appears that this could include a threshold consideration of reliability; however, it is important to remember that reliability is primarily an issue that goes to the weight to be given the evidence and not its admissibility125.

Other cases finding automatically generated metadata or ESI to be real evidence and subject only to authentication include R. v. Nardi, [2012] BCPC 318 at para. 22, R. v. Soh, [2014] NBQB 20 at para. 31, R. v. Mondor, 2014 ONCJ 135 at para. 17-19. R. v. Bernard (2016) finds that although aspects of the evidence is automatically generated metadata, Facebook screenshots are documentary evidence (and inadmissible due to lack of authentication)126.

6.0 Conclusions

Metadata is frequently generated automatically. Indeed, automatic creation and assignment of metadata can be an indicator of a well-developed information governance system127. Computer-generated metadata easily meets the test for real evidence and can be admissible after passing the authentication test. Increasingly, Canadian courts are acknowledging that automatically generated metadata need not fulfill the evidence tests related to documentary evidence.

Records professionals, who have ideally been involved in all stages of the record life cycle, are well-placed to be able to speak on how metadata was created. To properly characterize metadata as legal evidence, RIM professionals should consider using the three-way distinction described in Underwood and Penner: system, substantive, and metadata.

In determining the type of metadata as it relates to evidence, RIM professionals can start the analysis by considering whether the metadata has been created at the system-level of the network. System metadata has multiple legal purposes. Automatically-generated system metadata can be used in authentication during a trial for both documentary and real electronic evidence. System metadata itself is most likely to be considered real, rather than documentary, evidence.

Substantive metadata can be either documentary or real evidence. Automatically captured edit tracking, for instance, may be real evidence. Substantive metadata may also be evidence of human interaction and is likely to be considered documentary evidence.

Information professionals should be ready to provide information to satisfy the admissibility and weighting rules of documentary evidence, including business records exception to the hearsay rule, authentication through metadata, and proof of integrity of the system through expert testimony or other means.

Embedded metadata has caused some confusion in courts, such as the Animal Welfare rulings. Information professionals should be ready to clearly describe how metadata such as scripts or formulas are executed without human intervention. Otherwise, embedded metadata is likely to be considered documentary evidence, and information professionals should be prepared to satisfy the documentary evidence rules.

RIM professionals interact with, create, and manage metadata in numerous tasks during the course of their work. Although the legal uses of metadata are always evolving as case law advances, RIM professionals can benefit from a solid understanding of the Canadian legal framework and recent case law rulings on the topic. Armed with this knowledge, RIM professionals will be in a better position to make decisions about the automatic generation of metadata, how best to set up metadata profiles, and how to communicate important legal distinctions with IT and others on how metadata is used in Canadian courts today.

Publication bibliography

“ABA-LawyersCanSearch Metadata.” Information Management Journal May/June (2007): 11.

Aguilar v. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Div. of U.S. Dept. of Homeland Sec., 255 F.R.D. 350 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 21, 2008), November 21, 2008.

Alberta Evidence Act, R.S.A. c. A-18, s. 41 (1980), accessed on 2017-10-31, http://canlii.ca/t/52fmm. Animal Welfare International Inc. v. W3 International Media Ltd., 2013 BCSC 2193 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-30, http://canlii.ca/t/g23fg.

Animal Welfare International Inc. v. W3 International Media Ltd., 2014 BCSC 1839 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-30, http://canlii.ca/t/gds4d.

“Backgrounder: The Honourable Justice David M. Paciocco’s Questionnaire”. Department of Justice, Government of Canada. Last modified on April 07, 2017, https://www.canada.ca/en/department- justice/news/2017/04/the_honourable_justicedavidmpacioccosquestionnaire.html.

BL v Saskatchewan (Social Services), 2012 SKCA 38 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/fqtnj.

Bryant, Alan W., Sidney N. Lederman, Michelle K. Fuerst, and John Sopinka. The law of evidence in Canada.

Markham, Ont: LexisNexis, 2009.

Canada Evidence Act. RSC 1985, c C-5, (1985), accessed on 2017-10-31, http://canlii.ca/t/52zlc. Canadian General Standards Board, CAN/CGSB 72.34-2017 Electronic records as documentary evidence.

Gatineau, Québec: Canadian General Standards Board. 2017, accessed on 2017-10-31, http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/ongc-cgsb/P29-072-034-2017-eng.pdf.

Cook, Michael. The Management of Information from Archives. Aldershot, Hants, England, Brookfield, Vt., USA: Gower, 1986.

Currie, Robert, and Steve Coughlan. “Canada (Chapter 9).” In Electronic Evidence, 3rd edition, edited by Stephen Mason. 283–325. Lexis Nexis, 2012. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2324273.

Delisle, RJ. Evidence: principles and problems. 10th ed. Toronto: Carswell, 2010.

Desgagne v. Yuen et al, 2006 BCSC 955 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-09-01, http://canlii.ca/t/1nnpc. Duranti, Luciana. “From digital diplomatics to digital records forensics.” Archivaria 68 (Fall 2009): 39–66.

Duranti, Luciana, and Randy Preston. International research on permanent authentic records in electronic systems (InterPARES) 2: Experiential, interactive and dynamic records. CLEUP, 2008.

Duranti, Luciana, and Corinne Rogers. “Trust in Digital Records: An Increasingly Cloudy Legal Area.” Computer Law Security Review 28, no. 5 (2012): 522–31.

Duranti, Luciana, Corinne Rogers, and Anthony Sheppard. “Electronic Records and the Law of Evidence in Canada: The Uniform Electronic Evidence Act Twelve Years Later.” Archivaria 70, (Fall 2010): 95–124.

Duranti, Luciana, and Kenneth Thibodeau. “The concept of record in interactive, experiential and dynamic environments: the view of InterPARES.” Archival Science 6, no. 1 (2006): 13-68.

Evidence Act, RSO 1990, c E.23, accessed on 2017-10-31, http://canlii.ca/t/l1vl. Evidence Act, SS 2006, c E-11.2, accessed on 2017-10-31, http://canlii.ca/t/52w3h.

Force, Donald C. “From Peruvian Guano to Electronic Records: Canadian E-Discovery and Records Professionals.” Archivaria 69 (2010): 49–75.

Franks, Pat, and Nancy Kunde. “Why METADATA Matters.” Information Management Journal Sept/Oct (2006): 55–61.

Gable, Julie. “Examining metadata: Its role in e-discovery and the future of records managers.” Information Management Journal 43, no. 5 (2009): 28–32.

Gall. GL, FP Eliadis, and F Allard. The Canadian legal system, 5th ed. Scarborough, Ont: Carswell, 2004.

Halsbury’s laws of Canada: Civil Procedure. Markham, Ont.: LexisNexis, 2012. “Information Governance Maturity Model.” ARMA International, 2013.

Hummingbird v. Mustafa, 2007 CanLII 39610 (ON SC), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/1t0tp. InterPARES 3 Project. Terminology database, accessed on 2017-08-20,

http://www.interpares.org/ip3/ip3_terminology_db.cfm.

Isaza, John. “Metadata In Court: What RIM, Legal and IT Need to Know.” ARMA International Education Foundation, Pittsburgh PA, Nov 2010.

Jenkinson, Hilary. A Manual of Archive Administration. New and Revised. London: Percy Lund, Humphries Co. 1937.

Lemieux, Victoria, Brianna Gormly, and Lyse Rowledge. “Meeting Big Data challenges with visual analytics: The role of records management.” Records Management Journal 24, no. 2 (2014): 122-141.

Mancuso, Lara. “Exploring the Potential of Naming Conventions as Metadata.” Independent study paper, University of British Columbia, 2013.

Manitoba Evidence Act, R.S.M., c. E150 (1987), accessed on 2017-10-31, http://canlii.ca/t/lb8k.

Mason, Stephen. “Authentic Digital Records: Laying the Foundation for Evidence.” Information Management Journal 41, no. 5 (Sept/Oct 2007): 32–40. http://www.arma.org/bookstore/files/Mason.pdf.

Mason, Stephen. “Proof of the Authenticity of a Document in Electronic Format Introduced as Evidence.” ARMA International Educational Foundation, Pittsburg, PA, October 2006, accessed on 2017-08-25, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8ae3/d41b6c962d141ddb23640418ecaed6a0fa17.pdf.

McGarry v. Co-operators Life Insurance Co., 2011 BCCA 214 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/fl636.

Owens, Scott. “Best Evidence in Canada: An Analysis of Issues and Case Law” SSHIRC project paper, University of British Columbia, 2014.

Paciocco, D. M. “Proof and progress: Coping with the law of evidence in a technological age.” Canadian Journal of Law and Technology 11, no. 2 (2015): 181–228.

Preston, Randy. “InterPARES 2 Chain of Preservation (COP) Model Metadata” (Draft report). (2009).

RS II Productions Inc. v. B.C. Trade Development Corp., 2000 BCCA 674 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/1fnb1.

- v. Avanes et al., 2015 ONCJ 606 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-09-01, http://canlii.ca/t/gltb6.

- v Bernard, 2016 NSSC 358 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/h3w44.

- v Clarke, 2016 ONSC 3564 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gsldq

- v C.L., 2017 ONSC 3583 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/h4xxp.

- v. Hall, 1998 CanLII 3955 (BC SC), accessed on 2017-08-30, http://canlii.ca/t/1f7fx.

- v Hamdan, 2017 BCSC 676 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/h3xdd.

R v Hirsch, 2017 SKCA 14 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gxq03.

- v. J.S.M., 2015 NSSC 312 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gmmml.

R v. K.M., 2016 NWTSC 36 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gs4mv.

- v. MacDonald, 2016 ABPC 142 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gt5bd.

- v. Mondor, 2014 ONCJ 135 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-09-01, http://canlii.ca/t/g6986.

- v. Nardi, 2012 BCPC 318 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-09-01, http://canlii.ca/t/fspw2.

R v. Dennis James Oland, 2015 NBQB 245 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gp3w3.

- v. Oler, 2014 ABPC 130 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/g7n43.

- v. Starr, 2000 2 SCR 144, 2000 SCC 40 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/525l.

R v Nde Soh, 2014 NBQB 20 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/g50jc.

Rogers, Corinne. “Authenticity of Digital Records: A Survey of Professional Practice.” The Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science 39, no. 2 (2015): 97-113.

Rogers, Corinne, ed. Record Authenticity as a Measure of Trust: A View Across Records Professions, Sectors, and Legal Systems. Croatia: Department of Information and Communication Social Sciences, University of Zagreb (2015): 109-118.

Rogers, Corinne. “Virtual authenticity: authenticity of digital records from theory to practice.” PhD dissertation, University of British Columbia, 2015, accessed on 2017-08-20. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0166169.

Rowe, Joy. “Are you ready to create digital records that last?” Preparing users to transfer records to a digital repository for permanent preservation.” Journal of the South African Society of Archivists 49 (2016): 41- 56, accessed on 2017-10-31, https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jsasa/article/view/138427.

Rowe, J. “Why Manage when you can Govern? Metadata in the Canadian Legal System.” Poster presented at annual meeting of ARMA Canada, Saskatoon, SK. (June 2013), accessed on 2017-10-31, https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/graduateresearch/42591/items/1.0075797.

Rules of Civil Procedure, RRO (Ontario), Reg 194 — 1.04(1) (1990), accessed on 2017-10-31, http://canlii.ca/t/52zjn.

Sedona Canada. “The Sedona Canada Principles: 2008 CanLIIDocs 1.” The Sedona Conference Working Group 7 (WG7), Montreal, Jan 2008, fourth update (November 19, 2015), http://commentary.canlii.org/w/canlii/2008CanLIIDocs1en.

“The Sedona Principles, Third Edition: Best Practices, Recommendations Principles for Addressing Electronic Document Production: (2017 Public Comment Version).” THE SEDONA CONFERENCE, March 2017. https://thesedonaconference.org/publication/The%20Sedona%20Principle. .

The Sedona Conference Working Group. “THE SEDONA PRINCIPLES: Best Practices Recommendations Principles for Addressing Electronic Document Production.” June 2007.

Sheppard, A. F. “Records and Archives in Court.” Archivaria 19, Winter (1984): 196–203.

Shirley Williams, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Sprint/United Management Company, 464 F. Supp. 2d 1100 (D. Kan. 2006).

Swiss Reinsurance Company v. Camarin Limited, 2015 BCCA 466 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gm28z.

Thacker v Iamaw, District Lodge 140, 2016 BC LA 62600 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/gtsph.

Underwood, Graham and Jonathon Penner, eds. Electronic Evidence in Canada. Toronto: Carswell, 2010. Williams v. Sprint/United Management Co., 464 F. Supp. 2d 1100 (D. Kan. 2006).

Winstanley v. Winstanley, 2017 BCCA 265 (CanLII), accessed on 2017-08-27, http://canlii.ca/t/h4v5d.

Works Cited

1An earlier version of this research was published as a poster presentation and benefitted from the feedback of conference attendees: Joy Rowe, “Why Manage when you can Govern? Metadata in the Canadian Legal System.” Poster presentation, ARMA Canada, Saskatoon, 2013. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/graduateresearch/42591/items/1.0075797.

2Luciana Duranti and Randy Preston, International research on permanent authentic records in electronic systems (InterPARES) 2: Experiential, interactive and dynamic records (CLEUP, 2008); Randy Preston, “InterPARES 2 Chain of Preservation (COP) Model Metadata” (Draft report). (2009).

3Donald Force, “Peruvian Guano to Electronic Records: Canadian E-Discovery and Records Professionals,” Archivaria 69(2010); Pat Franks and Nancy Kunde, “Why METADATA Matters,” Information Management Journal (Sept/Oct 2006); Julie Gable, “Examining metadata. Its role in e-discovery and the future of records managers,” Information Management Journal 43, no. 5 (2009); John Isaza, Metadata in Court. What RIM, Legal and IT Need to Know (Pittsburg, PA: ARMA International Education Foundation, 2010); Stephen Mason, “Proof of the Authenticity of a Document in Electronic Format Introduced as Evidence” (Pittsburg, PA: ARMA International Education Foundation, 2006); Stephen Mason, “Authentic Digital Records. Laying the Foundation for Evidence,” Information Management Journal 41, no. 5(2007).

4Luciana Duranti and Corinne Rogers. “Trust in digital records: An increasingly cloudy legal area,” Computer Law Security Review 28, no. 5 (2012); Luciana Duranti. “From digital diplomatics to digital records forensics.” Archivaria 68 (Fall 2009).

5As noted in Force, many sources on legal rulings freely reference both US and Canadian rulings (2010, 54). This paper adopts his stricter view of juridical context and strives to cite only Canadian legal sources, when possible.

6There is a technical distinction between the terms “electronic” and “digital.” Courts have largely chosen the terms “electronic record,” “ESI” (electronically stored information), and “electronic/computer evidence.” Other recent literature tends to use “digital”. In the context of this article, I use the terms ‘electronic record’ and ‘digital record’ interchangeably unless there is a reason to give a distinction. 7 A. F. Sheppard, “Records and Archives in Court.” Archivaria 19 (Winter 1984).

8Luciana Duranti, Corinne Rogers and Anthony Sheppard, “Electronic Records and the Law of Evidence in Canada: The Uniform Electronic Evidence Act Twelve Years Later.” Archivaria 70 (Fall2010):96.

9Duranti, Rogers, and Sheppard, “The Uniform Electronic Evidence Act Twelve Years Later,” 96.

10Robert J. Currie and Steve Coughlan, “Chapter 9, Canada – Electronic Evidence in Canada,” in Electronic Evidence (3rd ed), ed. Stephen Mason (LexisNexis, September 1, 2012), 288.

11Hilary Jenkinson, A manual of archive administration (New and Revised. London: Percy Lund, Humphries Co., 1937): 4.

12Michael Cook, The Management of Information from Archives (Aldershot, Hants, England; Brookfield, Vt., U.S.A: Gower, 1986): 7, 129.

13InterPARES 3 Project Terminology database. http://interpares.org/ip3/ip3_terminology_db.cfm?team=15.

14Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada,” 289. Canada Evidence Act, RSC 1985, c C-5, s.31.1 and provincial evidence statutes that have adopted the Uniform Electronic Evidence Act provisions and have similar authentication rules for electronic documents. 15 Corinne Rogers, “Record Authenticity as a Measure of Trust: A View across Records Professions, Sectors, and Legal Systems,” INFuture2015: e-Institutions – Openness, Accessibility, and Preservation (The Future of Information Sciences. Croatia: Department of Information and Communication Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, 2015): 111.

16InterPARES 3 Project Terminology database. http://interpares.org/ip3/ip3_terminology_db.cfm?team=15

17An interesting study exploring the Chain of Preservation (COP) metadata schema to identify the basic units of metadata that could be usefully contained in a file naming convention was done by Lara Mancuso, “Exploring the Potential of Naming Conventions as Metadata,” (independent study project paper, University of British Columbia, 2013).

18Rogers, “Record Authenticity”, 112.

19Rogers, “Record Authenticity”, 97.

20ARMA International, “Information Governance Maturity Model,” (2013).

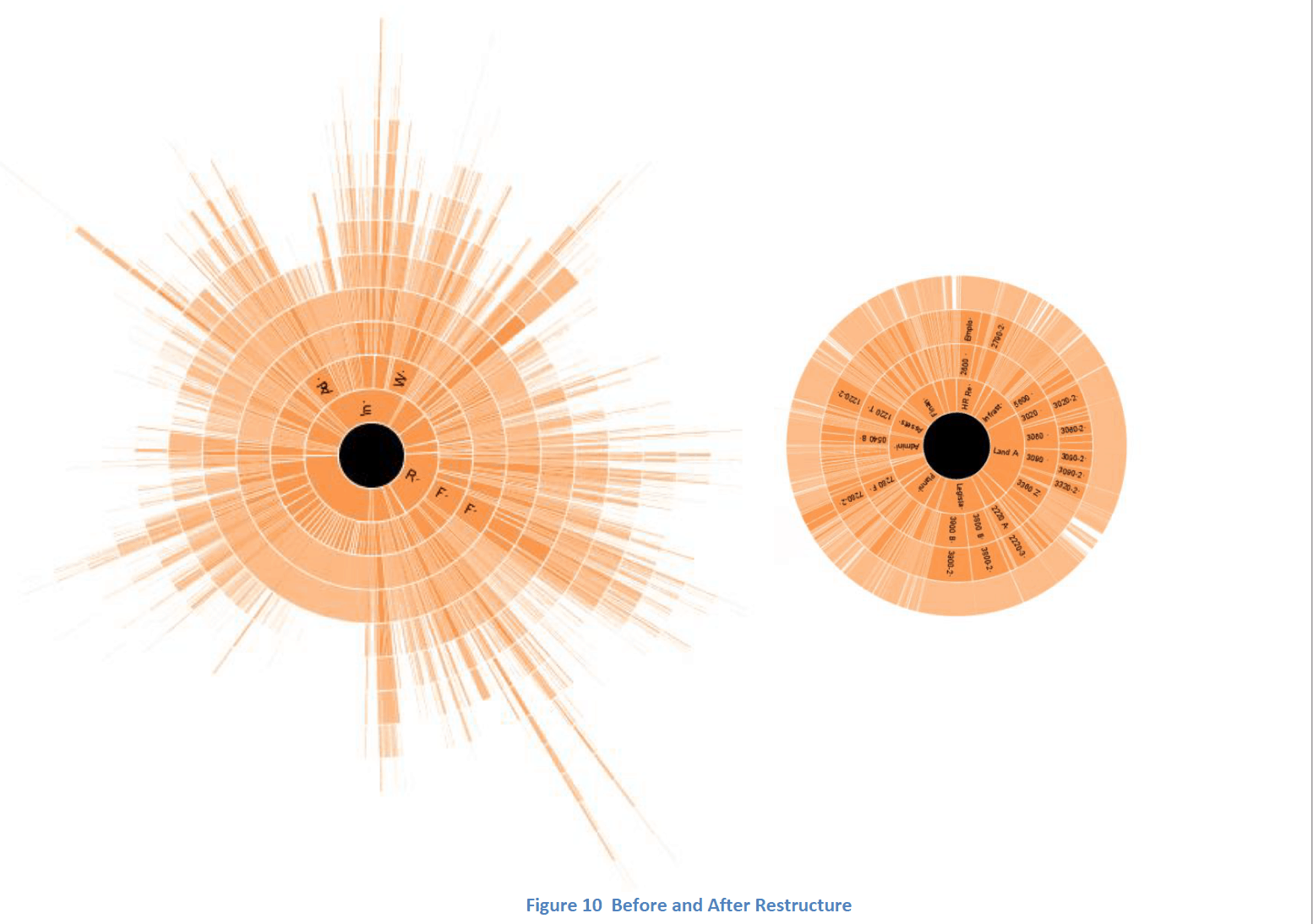

21Examples of use of The Principles® in assessing organizational records maturity include Joy Rowe,” ‘Are you ready to create digital records that last?’ Preparing users to transfer records to a digital repository for permanent preservation,” Journal of the South African Society of Archivists 49 (2016): 48; Victoria Lemieux, Brianna Gormly, and Lyse Rowledge, “Meeting Big Data challenges with visual analytics: The role of records management,” Records Management Journal 24, no. 2 (2014): 135-136.

25Pat Franks and Nancy Kunde, “Why METADATA Matters,” Information Management Journal (Sept/Oct 2006): 57.

26Stephen Mason, Proof of the Authenticity of a Document in Electronic Format Introduced as Evidence (Pittsburg, PA: ARMA International Education Foundation, 2006): 6-7.

27Sedona Canada, The Sedona Canada Principles. The Sedona Conference Working Group 7 (WG7), (Montreal, 2008, fourth update 2015): 8.

28Ibid., 8.

30Rules of Civil Procedure may relate to how witnesses are examined, how affidavits may be admitted, or how long before a trial another party must be notified to produce documentary evidence, Halsbury’s laws of Canada: Civil Procedure (Markham, Ont: LexisNexis. Halsbury 2012): 289.

31“ABA-Lawyers Can Search Metadata,” Information Management Journal (May/June 2007): 11. Shirley Williams, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Sprint/United Management Company, 464 F. Supp. 2d 1100 (D. Kan. 2006). This ruling followed changes in the US Federal Rules of Civil Procedures, which were amended in 2006 to address issues of electronically stored information, or ESI.

32Hummingbird v. Mustafa, [2007] 39610 ONSC.

33The Sedona Conference Working Group, THE SEDONA PRINCIPLES: Best Practices Recommendations and Principles for Addressing Electronic Document Production, (2007): 4.

34Ibid., 60.

35These same distinctions are maintained in the March 2017 Public Comment version of the proposed updated to the Sedona Principles. THE SEDONA CONFERENCE, The Sedona Principles, Third Edition: Best Practices, Recommendations and Principles for Addressing Electronic Document Production (2017 Public Comment Version).

36John Isaza, Metadata in Court. What RIM, Legal and IT Need to Know (Pittsburg, PA: ARMA International Education Foundation, 2010). 37 This three-way distinction of metadata is frequently attributed to US Sedona Principles. In fact, although the Aguilar case did cite Sedona Principles for some of the discussion of metadata, the terms “substantive, embedded, and system” come from US District Court for the District of Maryland, Suggested Protocol Rules for Discovery of Electronically Stored Information, 25-28. This correction of sourcing is important because a key Canadian legal text, Underwood and Penner, takes up the three-way distinction of metadata and this text is cited in several Canadian cases. The Maryland protocol that Aguilar cited has now been replaced by Principles for the Discovery of ESI in Civil Cases, and it uses the two-part distinction found in US Sedona Principles: system metadata and application metadata. Sedona Commentary on Ethics Metadata notes that the court in Aguilar collapsed some of the seven distinct types of metadata defined in the Sedona Glossary into the three categories of substantive, system-based and embedded (2013, p. 6, footnote 7).

38Julie Gable, “Examining metadata. Its role in e-discovery and the future of records managers,” Information Management Journal 43, no. 5 (2009): 30.

39Isaza, Metadata in Court, 8.

404.8% of the 293 respondents had given testimony in a court proceeding, while 10.2% had been involved in a legal hold or e-discovery. Corinne Rogers, “Virtual authenticity: authenticity of digital records from theory to practice” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 2015), 115, https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0166169.

41Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada,” 284.

42GL Gall, FP Eliadis, F Allard, The Canadian legal system, 5th Ed (Scarborough, Ont: Carswell, 2004), 40.

43Halsbury’s laws of Canada: Civil Procedure (Markham, Ont: LexisNexis, 2012), 289.

44Gall, Eliadis, and Allard, The Canadian legal system, 41.

45Halsbury’s laws of Canada: Civil Procedure, 285.

46Ibid., 286-287.

47Halsbury’s laws of Canada: Civil Procedure, 289.

48Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 284.

49Ibid., 285. British Columbia, Newfoundland, and Northwest Territories have not yet adopted a form of the coordinated electronic evidence legislation.

50Duranti, Rogers and Sheppard, “The Uniform Electronic Evidence Act Twelve Years Later,” 104-105.

51Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 285. 52 Underwood and Penner, Electronic Evidence in Canada, 12-1. 53 Ibid., 13-7.

54Ibid., 13-1 to 13-2.

55RJ Delisle, Evidence: principles and problems, 10th ed (Toronto: Carswell, 2010), 411.

56Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 295.

57Underwood and Penner, Electronic Evidence in Canada, 14-1.

58Saturley v. CIBC World Markets Inc [2012] NSSC 226 at para. 28.

59Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 284-285.

60Ibid., 285.

61Underwood and Penner, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 11-3, 11-7.

62Canada Evidence Act, RSC 1985, c C-5 (1985), s.31.2 (1).

63Ibid., s.31.3-b.

64Canada Evidence Act, RSC 1985, c C-5, s.31.3-c.

65Ibid., s.31.6(1).

66Ibid., s.31.5.

67Ibid., s.31.2(2).

68Underwood and Penner, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 12-1.

69Ibid., 13-8 to 13-9.

70Ibid., 12-1.

71Ibid., 12-13.

72Ibid., 12-2.

73Ibid., 12-5.

74Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 291. 75 Underwood and Penner, Electronic Evidence in Canada, 12-8. 76 Saturley v. World CIBC Markets [2012] NSSC 226.

77Ibid., 16.

78Underwood and Penner, Electronic Evidence in Canada, 12-9.

79Ibid.,12-9.

80Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada”, 291. In the Saturley ruling data that was automatically generated by software to register investment trading transactions was determined to be real evidence. It was not a ‘document’ and not therefore subject to the “presumption of reliability designed to satisfy the best evidence rule”.

81Underwood and Penner, Electronic Evidence in Canada, 12-15.

82Ibid., 12-10.

83Ibid., 12-13 to 12-14.

84Ibid., 12-16. This three-way distinction was initially proposed in the US Aguilar ruling, drawing on US Sedona Principles and Maryland Protocol for electronic discovery purposes, and has been extended by Underwood and Penner to apply to ESI for evidence purposes.

85Ibid., 12-17 to 12-18.

86Ibid., 12-19.

87Ibid., 12-19.

88Ibid., 12-20.

89According to the Canlii.org database, 288 cases have mentioned “electronic evidence”, “computer evidence” or “metadata” in the case rulings since 1979. Ninety-one percent of the cases have been within the last ten years (search conducted on August 30th, 2017).

90McGarry v. Co-operators Life Insurance Co, [2011] BCCA 214.

91RS II Productions Inc. v. B.C. Trade Development Corp [2000] BCCA 674 at para. 25 cites numerous rulings and quotes R. v. Starr, [2000] 2 SCR 144, 2000 SCC 40 “the Court has advanced towards what it calls a “principled approach” to the hearsay rule and instructed courts to consider necessity and reliability in each particular case, as opposed to applying “ossified rules” of evidence.”

92McGarry, BCCA 214 at para. 67.

93Canada Evidence Act, R.S.C., c. C-5, s.42 (1985).

94Manitoba Evidence Act, R.S.M., c. E150 (1987); Saskatchewan Evidence Act, R.S.S., c. S-16, ss. 55-56 (1978); Alberta Evidence Act, R.S.A. c. A-18, s. 41 (1980); and Ontario Evidence Act, R.S.O., c. E-23, s. 34.1 (1990).

95McGarry, BCCA 214 at para. 73-77.

96Ibid., at 81.

97Cases citing McGarry: Swiss Reinsurance Company v. Camarin Limited, [2015] BCCA 466 at para. 67 Winstanley v. Winstanley, [2017] BCCA 265 at para. 64.

98Scott Owen’s SSHIRC-funded study on the best evidence rule highlighted the rule as an ineffectual mechanism of admissibility in “Best Evidence in Canada: An Analysis of Issues and Case Law” (project paper, University of British Columbia, 2014).

99Currie and Coughlan, “Electronic Evidence in Canada.” 288.

100Ibid., 285.

101BL. v. Saskatchewan (Social Services) [2012] SKCA 38 at para. 41.

102R. v. Hamdan, [2017] BCSC 676 at para. 82.

103Alan W Bryant, Sidney N. Lederman, Michelle K. Fuerst, and John Sopinka, The Law of Evidence in Canada (3d) ed. (Markham: LexisNexis, 2009), 1225.